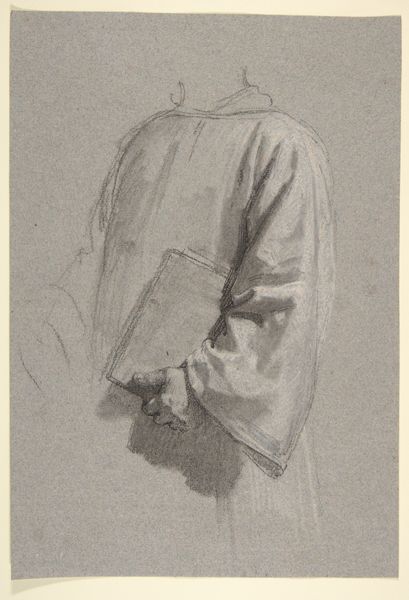

drawing, paper, pencil

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

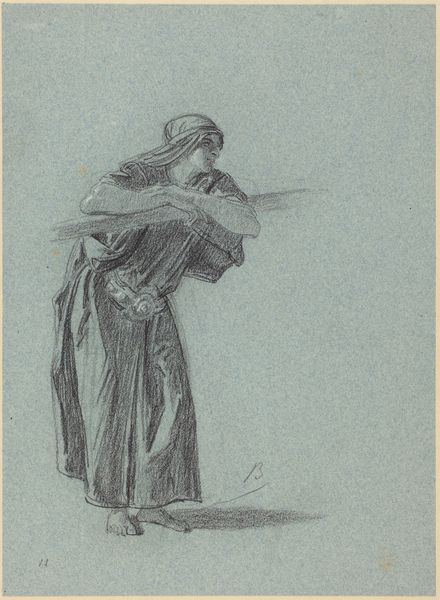

figuration

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

idea generation sketch

#

pencil drawing

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pencil work

#

genre-painting

#

realism

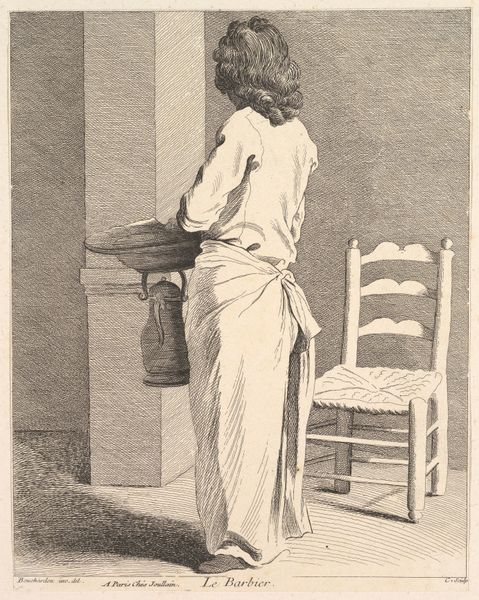

Dimensions: height 185 mm, width 135 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at "Rustende dienstmaagd met een mand, op de rug gezien," by Hermanus van Brussel, made sometime between 1773 and 1815… well, my first thought is, "aching back!" Editor: Exactly! You can practically feel the weight in this simple pencil drawing. I am immediately drawn to the lines, the very evident pencil strokes – you can almost feel the texture of the paper itself, can't you? Curator: Absolutely. And that’s precisely what intrigues me. The sketch, almost a preliminary gesture, speaks volumes about labor and everyday life, elevating the mundane to a poignant observation. But notice how the face is obscured, intentionally erasing individuality in favor of this universal symbol. She becomes every working woman, eternally burdened. Editor: It’s not just about the ‘every woman,’ but also about the labor made invisible. How the drawing mimics this invisibility through the fragility of pencil and paper, these inexpensive materials that are themselves a product of significant processing, the transformation of wood pulp. Curator: But isn't there beauty in that humility? It is more romantic when considering the simple materials used to portray someone whose life probably felt equally, perhaps even purposefully, unremarkable to others at the time. A romantic lens turns this lack into the maid's dignity, if you will. Editor: It's romanticizing a brutal economic reality, isn't it? It’s less about some inherent beauty than it is about systems of exploitation—of unseen labor that creates wealth but gets nothing in return, represented here by readily available paper. I suspect van Brussel never lifted a basket himself. Curator: Oh, but now you're venturing into dangerous waters. Dismissing the art simply because of its materials disregards the empathy, however flawed, conveyed by the artist. Editor: Flawed, exactly. It serves to make work, labor and exploitation beautiful through an accessible medium—one that asks the viewer to reflect on beauty more so than economic or human cost. Curator: Hmm, perhaps we're both correct, seeing two sides of the same coin, art. Editor: Perhaps… sides dependent on who gets to hold it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.