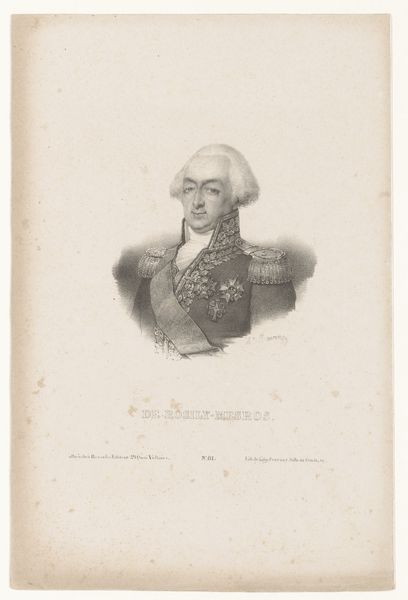

Portret van Ferdinand I, koning der beide Siciliën 1816 - 1825

0:00

0:00

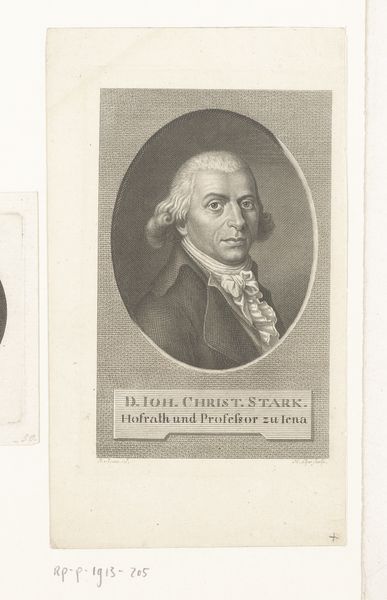

johannfriedrichbolt

Rijksmuseum

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

personal sketchbook

#

pencil drawing

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pencil work

#

sketchbook art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 105 mm, width 72 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

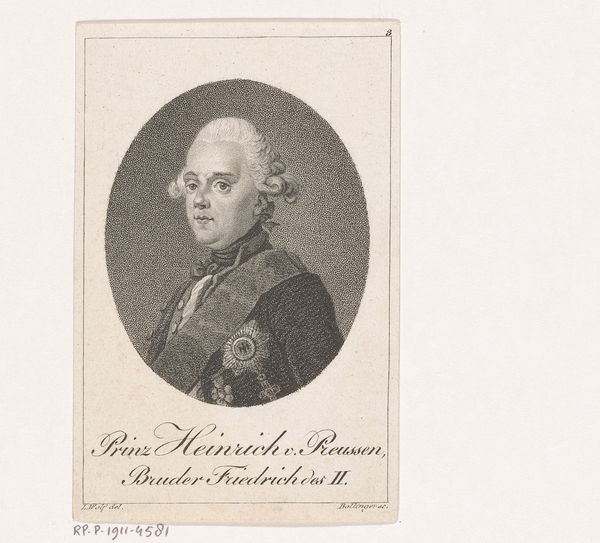

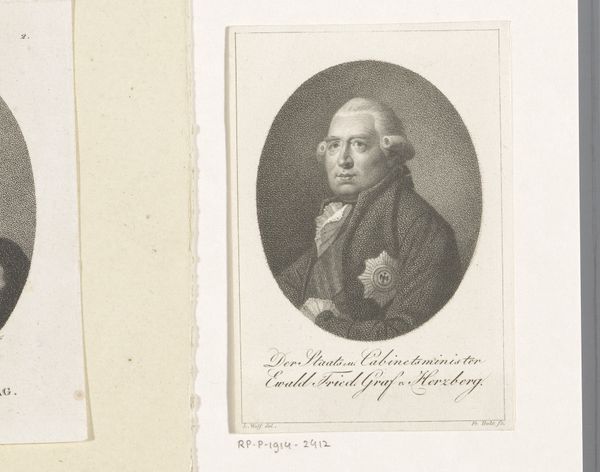

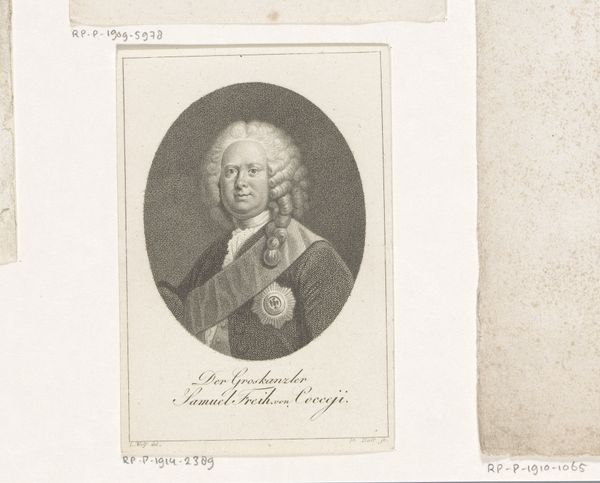

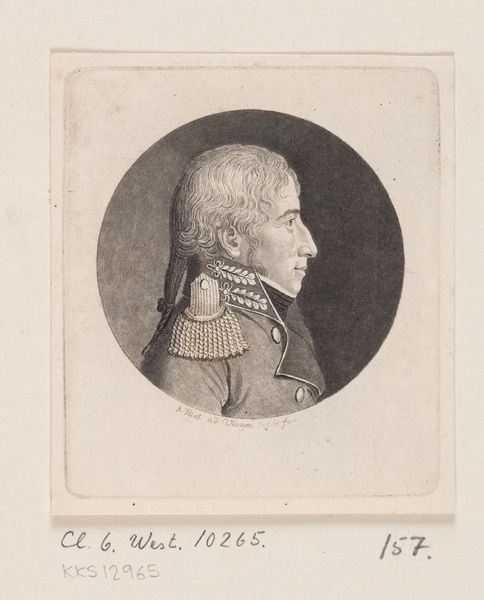

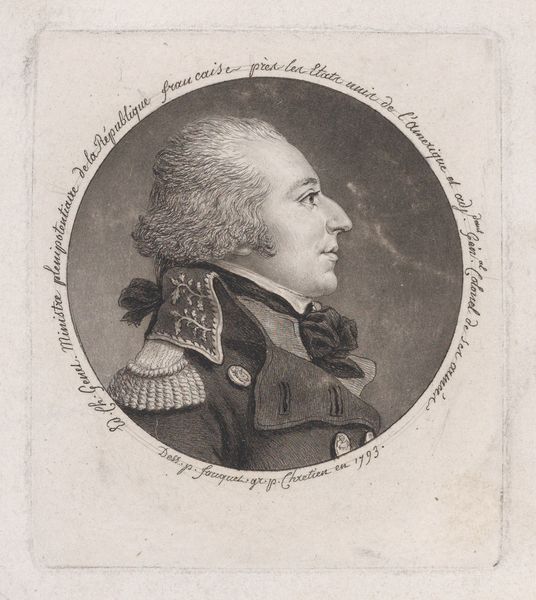

Curator: This engraving from somewhere between 1816 and 1825, housed here at the Rijksmuseum, presents a portrait of Ferdinand I, King of the Two Sicilies. It's the work of Johann Friedrich Bolt, rendering a regal air in print. Editor: It feels almost like a ghost. That pale face emerging from the stark white paper, and all those medals glittering with reflected light…there's a spectral quality to it, isn’t there? Curator: The choice of engraving definitely reinforces that sensibility. Engraving lends itself to sharp, clear lines which artists in this period used to capture authority. Consider the historical context. This portrait arrives after periods of intense social upheaval. How should Ferdinand project himself? Bolt and Ferdinand want to broadcast enduring power. Editor: Absolutely. Those medals, though…they aren’t just symbols of personal valor, are they? They become emblems of continuity, of legitimacy—a king linking himself to ancient orders and ideals, visually anchoring himself amidst change. It's carefully orchestrated propaganda, of course. Curator: Exactly. The Neoclassical style plays its part too, referencing classical authority and Roman ideals. Ferdinand sought to connect his rule with that grand narrative. Even the profile view invokes those Imperial Roman coins designed to evoke authority. Editor: But there’s something…vulnerable in his expression. Look at the downturn of his mouth, the almost weary set of his eyes. Does it suggest an awareness of the precariousness of his position? It almost adds an element of human complexity amidst the otherwise calculated symbolism. Or am I reading too much into it? Curator: No, I see it too. These portraits existed within the political theater, intended for specific audiences. They weren’t solely declarations of power, but pleas for recognition. After all, he would’ve still needed to consolidate support in the wake of war. Editor: An interesting reminder that images are always enmeshed within power dynamics and individual emotion. Curator: And the way we perceive that push and pull of power, status and self changes across the years.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.