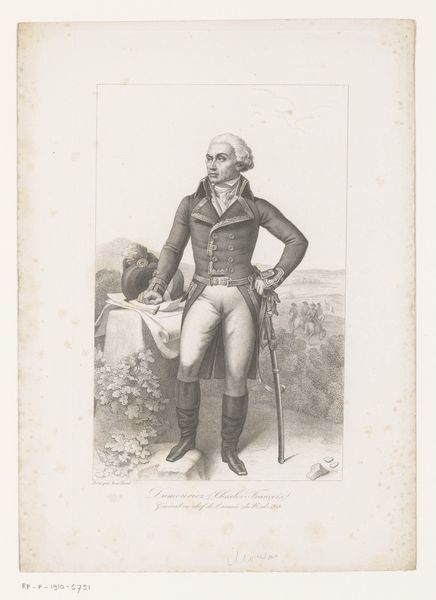

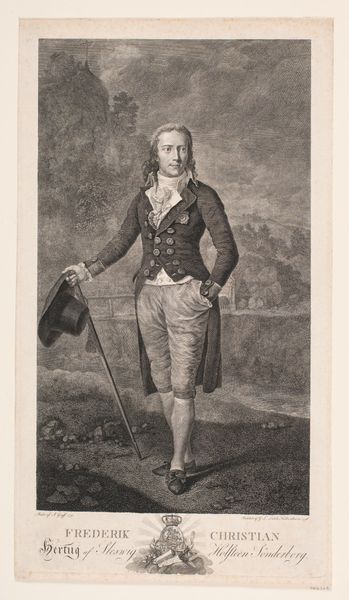

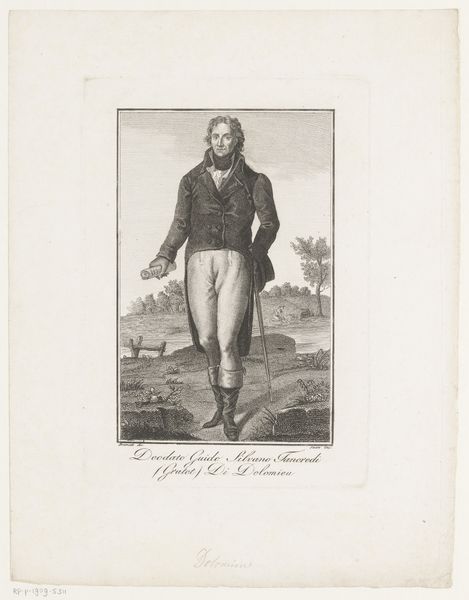

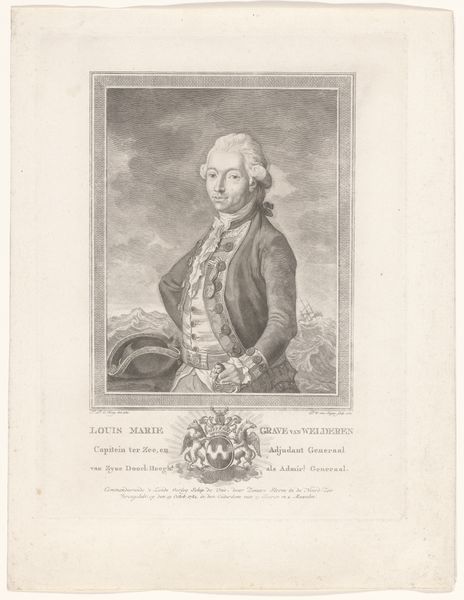

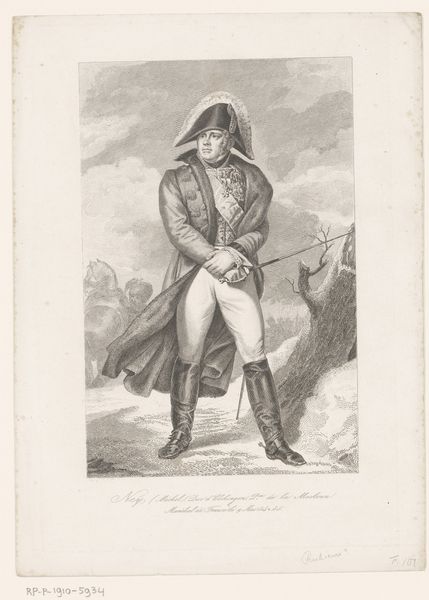

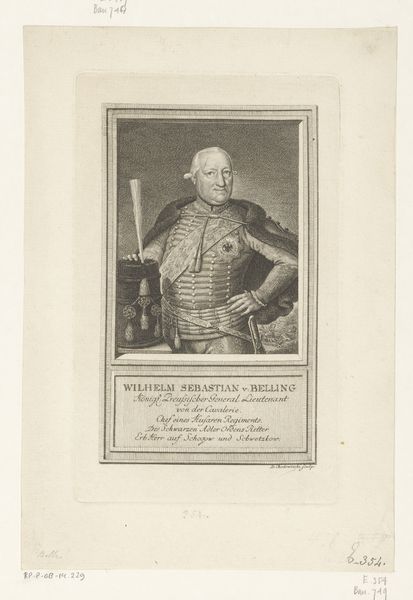

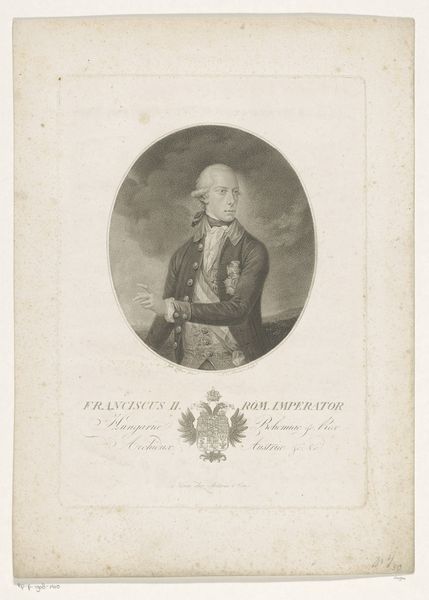

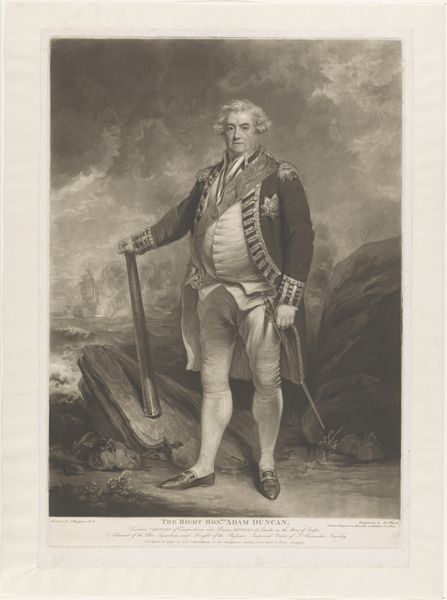

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

historical photography

#

pencil drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 520 mm, width 367 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this print, dating back to 1807, we see Jean Baptiste Fosseyeux's depiction of "Portret van Manuel Godoy." Editor: It’s remarkably austere, even cold. Despite the finery of the subject’s clothing and the neoclassical background, there’s an air of melancholy, a sense of foreboding. Curator: Godoy himself was a controversial figure. He rose to power as a favorite of the Spanish royal family. Prints like these acted as visual endorsements. See how his garments, rich in ornamentation, project power. Consider the symbolism invested in neoclassical design, reflecting an empire and its desire for stability and a return to classical order during turbulent times. Editor: But history paints a different picture, doesn't it? This image is pure propaganda. The print’s date, 1807, situates Godoy near the peak of his influence, before his fall from grace during the Napoleonic Wars. The "Prince of Peace", as his title claims below the portrait, was in reality, a facilitator to Napoleon, which later opened the door for the French invasion of Spain. Curator: Indeed. And in that light, elements become laced with irony. For instance, the armillary sphere represents his global dominion, reflecting imperial ambitions of control—of people, of trade routes, of destiny. Editor: And how complicit was he? Did he comprehend that the decisions made during this period undermined not only the monarchy but also centuries of cultural development? The image, however elegant, hints at the moral compromises made behind closed doors, even suggesting an impending doom. Curator: It illustrates how portraits aren't objective likenesses, but constructions. Even simple composition and dress act to influence public perceptions. Editor: Right. As we contemplate such imagery, it's important to critically engage with its implicit narratives of identity and legacy. Images outlive us all, for better or for worse. Curator: Indeed. Analyzing its forms, we understand the ways images like this participated in maintaining ideological control. Editor: Leaving us to ponder how images work today to produce both reality and, too often, delusion.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.