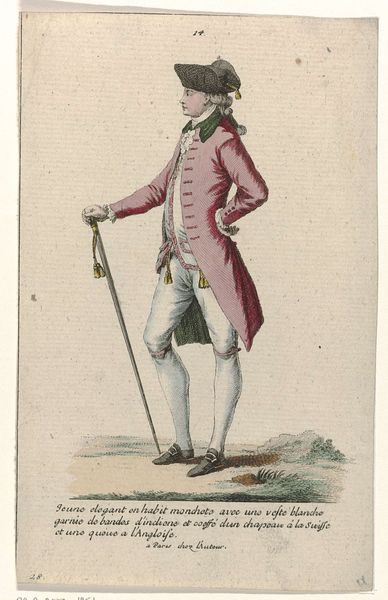

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

15_18th-century

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 359 mm, width 228 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Mathias de Sallieth's 1789 print, "Portret van Willem V, prins van Oranje-Nassau," depicts the Prince of Orange-Nassau in full regalia. Editor: It's predominantly monochrome, reddish-brown. Even though it's just an engraving, I can appreciate the intricate texture. It looks delicate, doesn't it? Like something that might crumble if you breathed on it wrong. Curator: Absolutely. That sepia tone evokes a specific mood. Consider how it casts Willem V. He stands confidently, almost posed, amidst a landscape seemingly crafted for his glorification. That pastoral background becomes another symbolic layer, evoking themes of dominion and heritage. Editor: The man knew how to dress! Look at all the frills. That’s a considerable investment in materials, in labour... The paper stock itself speaks to wealth, doesn't it? What does his attire tell us? Curator: Oh, his dress tells a complex story! That sash, the embroidery—they aren’t mere decoration. They embody power. Symbols like these, carefully rendered and displayed, construct an image of legitimate authority. Think about the continuity; Willem V stands within a tradition, not just of dress, but of rule. Editor: The hat casually displayed beside him—it is almost as if he is saying, “See how easily I bear the weight of responsibility?” What’s also striking is how the background simplifies and idealizes the scene. Not a brick building in sight. Only ‘nature’. Curator: Well, the Neoclassical movement adored its romanticized landscapes. Each element is intended to signal control, order, the taming of nature, paralleling his role in society. A constructed natural space becomes his stage. Editor: True. All these symbolic elements were certainly a production in itself. I’m thinking of the engraver, the paper maker, and the distributors... The networks of production were immense and reliant on exploited labour across the Dutch empire. It would be a complete misunderstanding if viewers associated such portraiture as naturalistic or inevitable. Curator: Well said. And now, considering the upheaval happening during the French Revolution, just across the border, we can sense how carefully constructed images like these were used as propaganda. Editor: An assertion of power, material display as message and... yes, it tells a grand tale of art and industry intertwined in a pivotal historical moment.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.