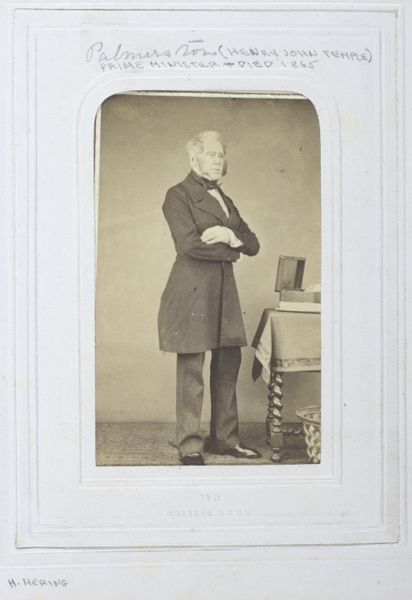

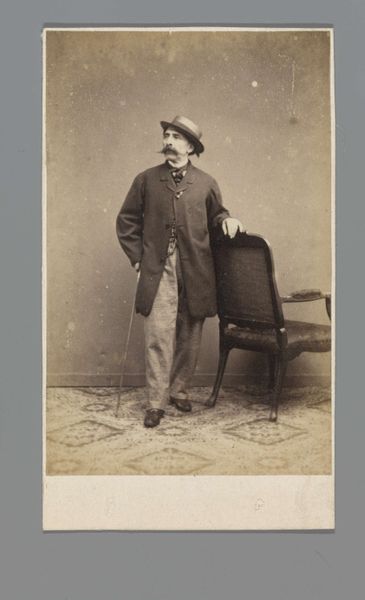

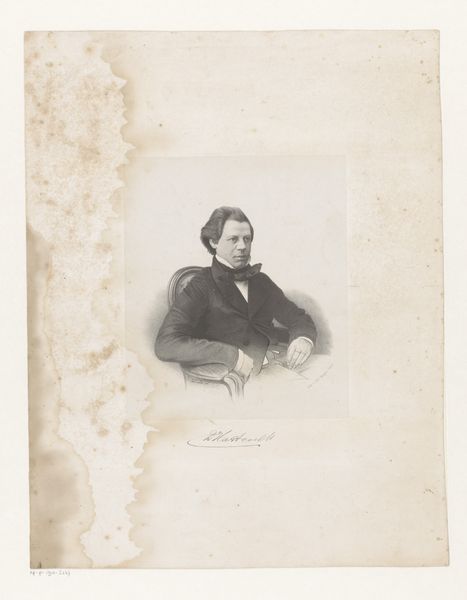

silver, print, photography

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

silver

# print

#

photography

#

19th century

Dimensions: 7.2 × 3.5 cm (image); 9.1 × 5.9 cm (paper); 10.2 × 6.2 cm (card)

Copyright: Public Domain

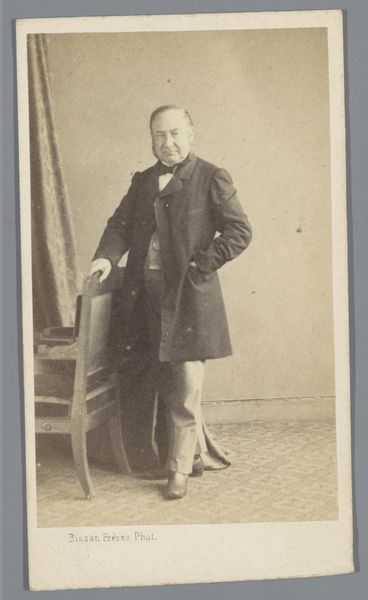

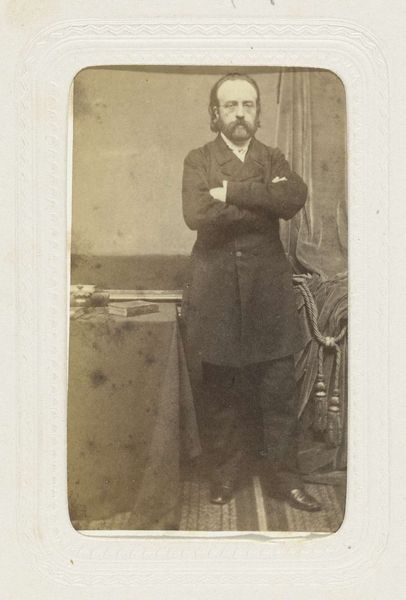

Curator: This photographic print, simply titled "George Cruikshank," comes to us from the 1860s. The photographers are W. Walker and Sons, operating out of London. It is a silver print, now residing at The Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: Immediately striking is the rather melancholic, almost subdued tone of the piece. The subdued palette, the somewhat slouched posture of the sitter. The image feels like a still moment caught amidst the bustle of Victorian London. Curator: Indeed. Cruikshank was a well-known caricaturist and illustrator, very active in social and political commentary through his art. This portrait, by contrast to his known satirical works, presents a far more intimate portrayal of the man. Think about the market for such photographs: the rise of portraiture amongst the middle classes in the 19th century. Photography allowed for wider circulation and a democratization of the image. Editor: The composition is deceptively simple, yet effectively divides the frame. On one side, the man, slumped ever so slightly, caught in a moment of quiet reflection. And on the other, the stark easel, and blank canvas. It acts as a stark juxtaposition: creation and contemplation sitting side-by-side. What do you read into the crisp lines of the easel against the sitter's more gentle curves? Curator: Perhaps that reflects a moment of uncertainty. He's looking to the easel and waiting for something to begin? The fact it's a photograph itself signals a shift in how artists wanted to be seen. Rather than relying solely on painted portraits commissioned by the wealthy, photographers captured more realistic—or perceived realistic—representations, thus changing an artist’s relationship with his image. It raises the question: What did Cruikshank want to convey about himself here? Editor: An important shift. Now that I know this context, the bare canvas almost feels poignant, as it opens the image to numerous possibilities. I think the appeal resides in how the arrangement facilitates questions rather than purporting conclusive statements about Cruikshank and his work. Curator: Precisely. I would agree that seeing his likeness represented by the mechanical eye, and made widely available as such, makes for a captivating artifact and moment in the history of representation. Editor: It seems a fascinating example of how a portrait can tell two tales—one of artistic practice and another about an evolving public sphere.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.