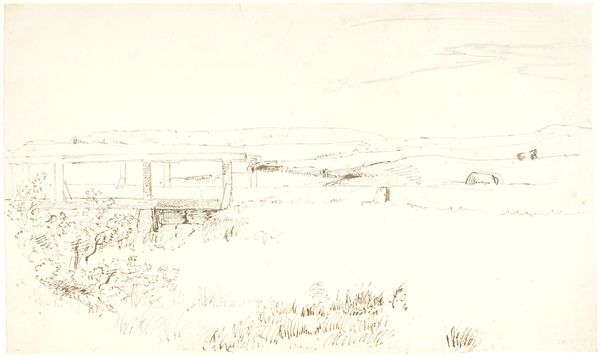

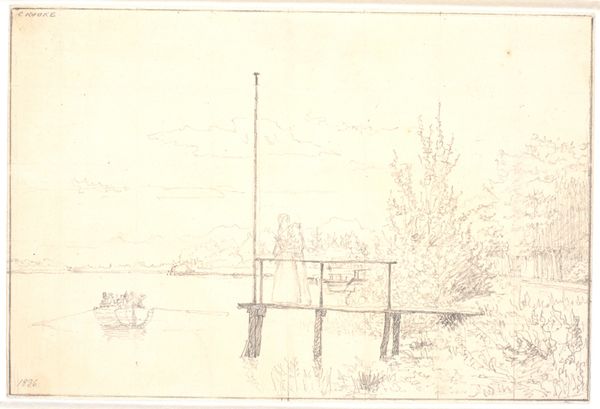

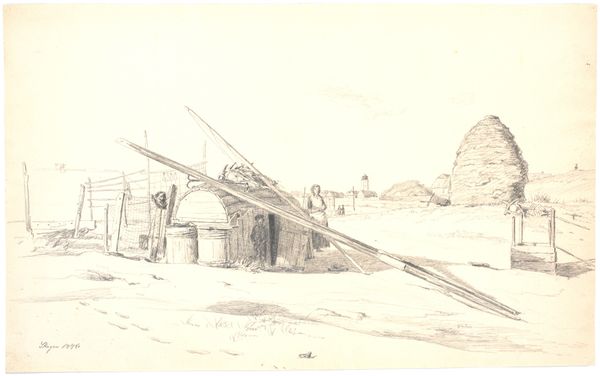

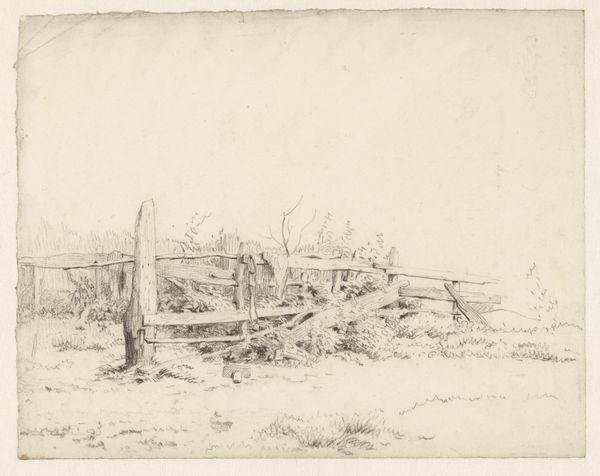

drawing, pencil

#

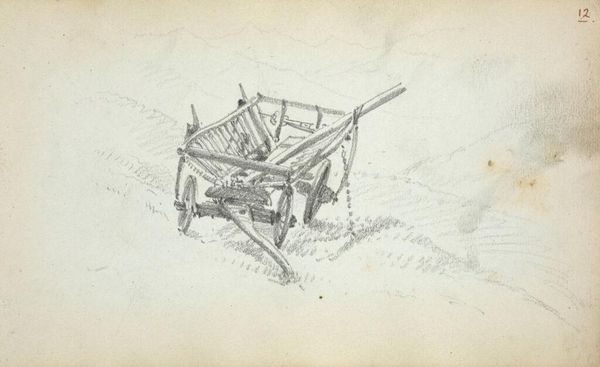

landscape illustration sketch

#

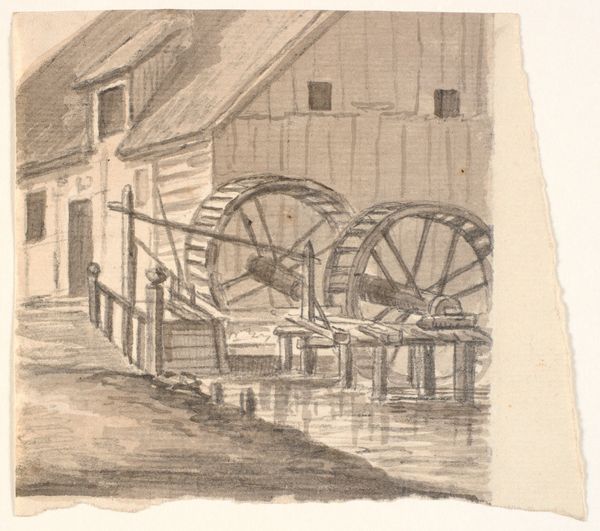

drawing

#

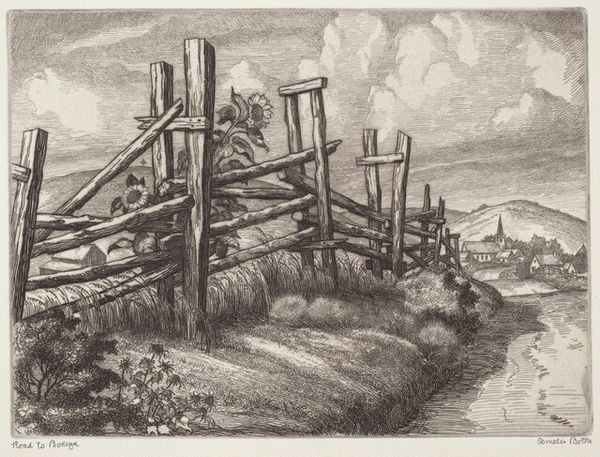

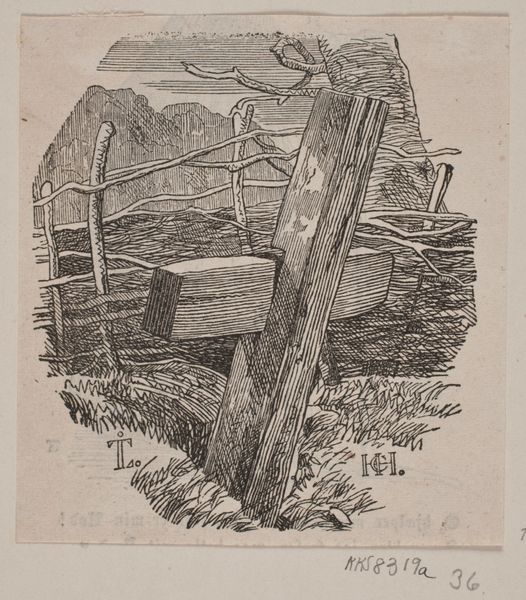

mechanical pen drawing

#

pen illustration

#

pen sketch

#

landscape

#

ink line art

#

personal sketchbook

#

linework heavy

#

romanticism

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pencil

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

realism

#

initial sketch

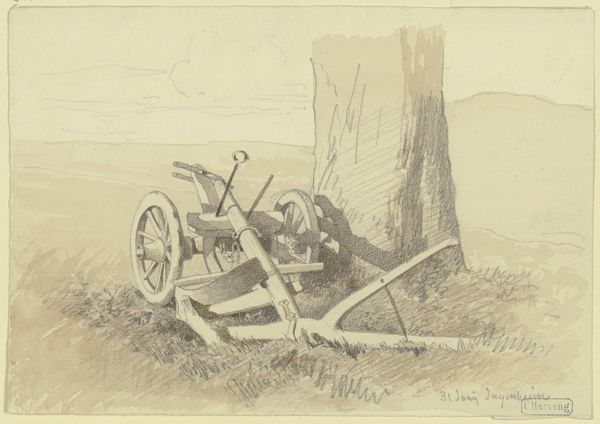

Dimensions: 217 mm (height) x 278 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Curator: This delicate drawing captures a coastal scene in Skagen, Denmark, circa 1847, by Martinus Rørbye. It’s titled "Strandparti med bådeplads, Skagen" and rendered meticulously with pencil and ink. Editor: It's bleak, isn’t it? Despite the light touch, there’s something undeniably melancholic about this rendering of a beach landing, skeletal forms suspended as bait perhaps or remnants of the day's catch? A grim visual document of the labor involved in existing. Curator: The "bådeplads," or boat place, suggests more than just the activity of landing boats. Look at the meticulousness in each stroke suggesting labor and transience, the rough-hewn wooden structures—symbols of human intervention in this stark landscape. The lone figure observes—perhaps he, too, is transient. Editor: Rørbye positions us in a historical moment when Danish fishing communities were profoundly shaped by environmental precarity and socio-economic stresses, even exploitation. Are we meant to consider who controls access to this 'bådeplads,' who benefits, who remains excluded from the frame entirely? This single figure seems resigned to the marginalization of life here, set in opposition to nature. Curator: The realism here, however, cannot be ignored. These very particular visual tropes capture a sense of timelessness as an everyday moment for Danish fishing culture, each object serving as a symbol. The boats, the rigging, and that ambiguous object – an animal hide? - convey specific knowledge and experience from which broader audiences have, generation after generation, interpreted into a general symbol about the cultural importance of life by the sea. Editor: Yes, but consider who controls that narrative, that “cultural importance.” This sketch visualizes specific elements that likely carried coded political and social meanings when displayed to contemporaneous viewers that could escape current reading or access today. Where did he decide to place that human figure, who could have told other kinds of histories if given artistic space to do so. Curator: Indeed. In Rørbye’s romantic gaze we now recognize it is through the eyes of a transient outsider we're given a brief glimpse into a harsh and elemental environment, with subtle gestures that, while personal, speak volumes about collective history. Editor: Ultimately, seeing art from this period necessitates recognizing artmaking is both an individual expression and enmeshed in social and historical dynamics—revealing those systems even through what is chosen to depict or elide.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.