drawing, ink, pencil

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

ink

#

pencil

#

realism

Copyright: Public Domain

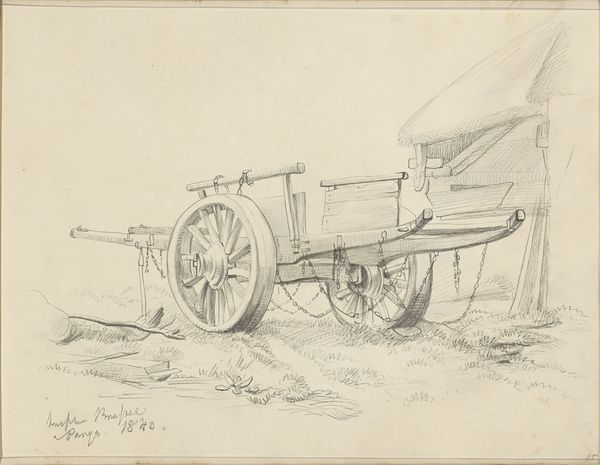

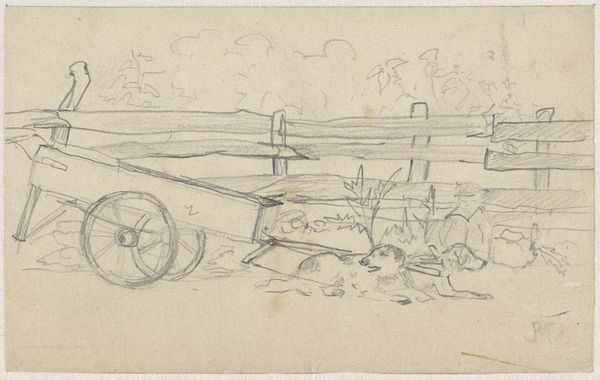

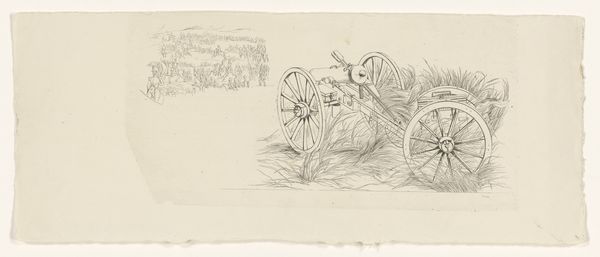

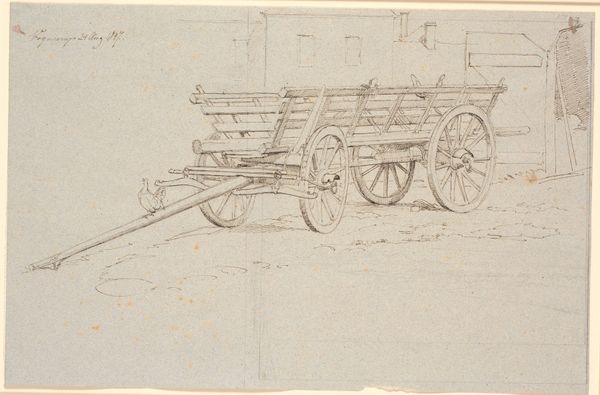

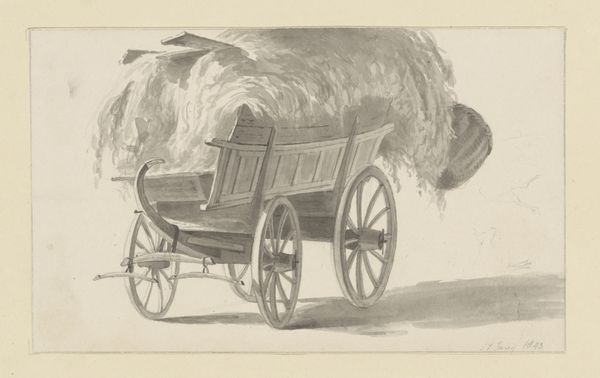

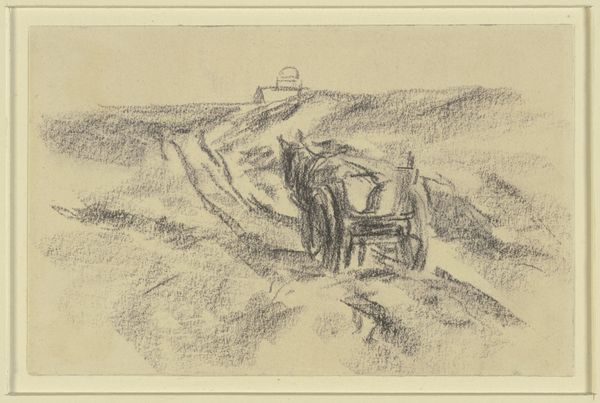

Curator: Here we have a piece called "Plough underneath a tree" by Karl Friedrich Harveng, a drawing executed in pencil and ink, currently held here at the Städel Museum. Editor: It’s striking, isn’t it? A stillness captured, but with a looming sense of labor. There's a humble quiet to the discarded plough; a temporary respite after what must have been exhausting work, perhaps during a pause in the day. Curator: Absolutely. The iconography of the plough itself is rich. Throughout history, it symbolizes agricultural work and, consequently, life's provision. Placing it under a tree enhances that. Think about the tree as a symbol for growth and shelter, it further amplifies ideas about nurture, fertility and protection. The choice of the subject itself invites examination of man's relationship to the earth. Editor: Yes, but consider also the physical reality of the drawing. The rough pencil and ink strokes render the texture of the soil, the heavy wood of the plough, the coarse bark of the tree; materials undergoing stress and weathering through daily exploitation. There's no idealization of rural life here, merely an honest representation of labor and land. Curator: Indeed, and yet, notice the composition, a dialogue between geometric precision with that of the manufactured plow set against the free, flowing form of the organic landscape, including the almost hazy background. There is an invitation to read the symbolism on different levels. Look at how the artist subtly creates tension, or maybe a union, between industry and nature. Editor: What intrigues me is what this means for our understanding of craft. This plough represents industry but we are not glorifying mechanization of agriculture here; instead, Harveng gives respect to the physicality of labour, with tools being essential to farming life, it depicts how a technology is entwined with human effort. What does such technology represent for how these men, how our ancestors, subsisted? Curator: Interesting point, because the drawing, at least for me, speaks volumes. It whispers to our inherited relationship with farming and our own origins with agricultural traditions, or at the very least, references something fundamentally historical that we may still recognize and feel connected to, whether subconsciously or explicitly. Editor: Ultimately, for me it comes down to honoring our ancestors whose labour created and fed our material existence, perhaps our present existence here now in this museum is related. This image serves as both memory and respect for how our very landscapes have been shaped.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.