engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

#

charcoal drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 317 mm, width 247 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

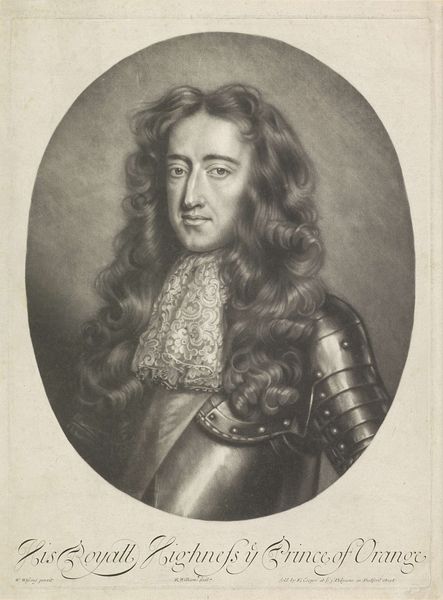

Curator: Oh, this piece! "Portret van Willem III, prins van Oranje"—Portrait of William III, Prince of Orange. It’s an engraving, dating from between 1670 and 1749, part of the Rijksmuseum collection. Editor: Immediately striking is this incredible balance, between the formality demanded of royal portraiture, and the almost haunted look in William's eyes. The monochromatic engraving adds to that sense of history and, frankly, a bit of unease. Curator: Unease is interesting! To me, there's also a powerful stillness. Engraving is so linear, right? It forces this calm observation. Plus, that ornate lace collar juxtaposed with the rigid armor, it whispers about the complexities of power, then and now. Editor: Exactly! Think about the politics of portraiture in that era. Who got immortalized? Who had access? And consider William's role. He’s literally encased in symbols of power. That armor, the implied military strength – it’s carefully constructed propaganda as much as personal depiction. But is he the subject or an object in service to colonial imperatives? Curator: Propaganda isn't inherently a bad thing. It can also reflect ambition and leadership! Editor: That is where we differ: those leadership skills involved the maintenance of oppressive structures and participation in transatlantic slavery. Even though the piece doesn't explicitly show it, its history haunts the frame, I would suggest. How do we look at that lace, that armor, understanding where the money came from? Curator: But what about the artistry? Look at the skill required to capture that level of detail! Every line meticulously placed to create the illusion of texture, of depth, of life...that in itself has value. Editor: Absolutely, technically it's brilliant! But as viewers, aren’t we obligated to see beyond the technique and grapple with the ethical questions the subject embodies, like war, imperialism, colonization and questions about national identity? Curator: Yes, both are essential I believe. Recognizing beauty doesn’t erase the difficult history but allows us to reflect on it in a different light. It adds another dimension to our understanding. Editor: Right, we have to confront what the image silently perpetuates or normalizes about wealth and social inequality in 17th and 18th century Netherlands. Curator: Food for thought as always, as we confront our inherited legacies and narratives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.