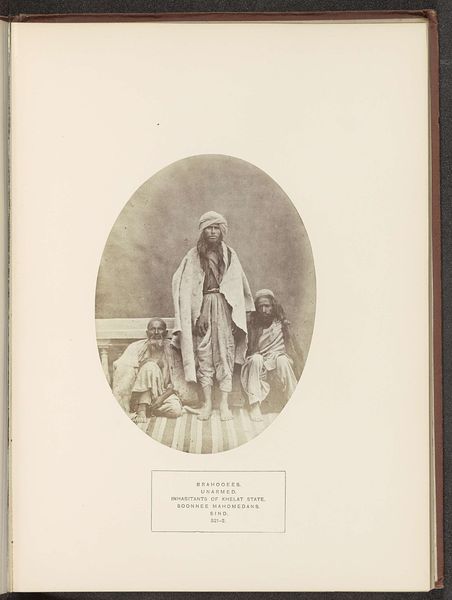

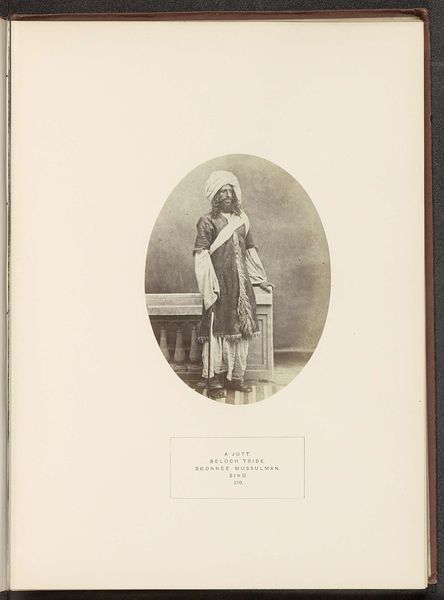

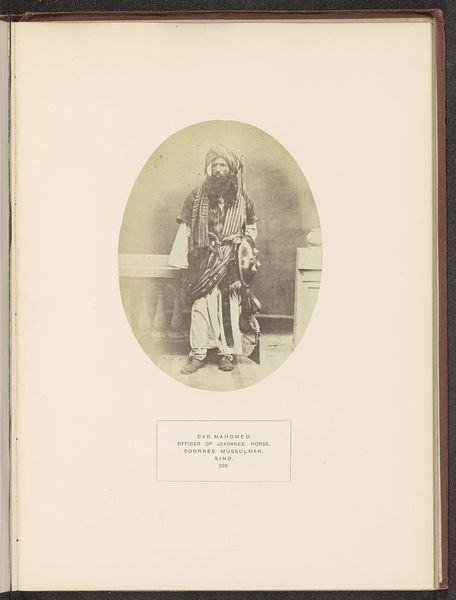

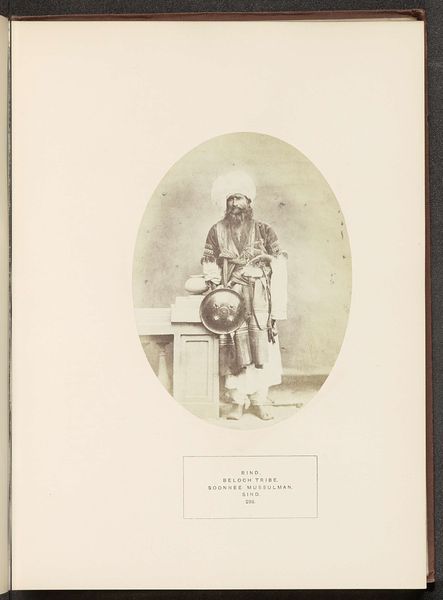

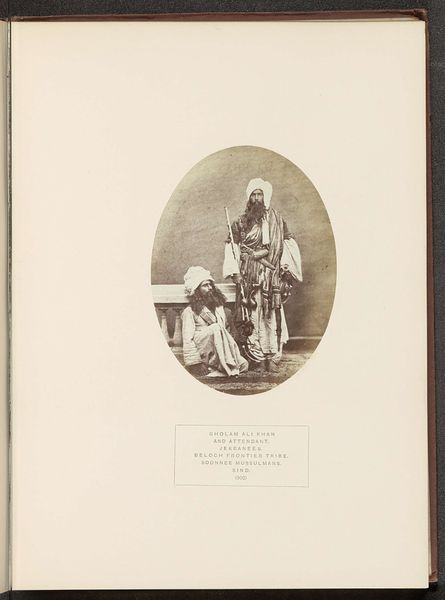

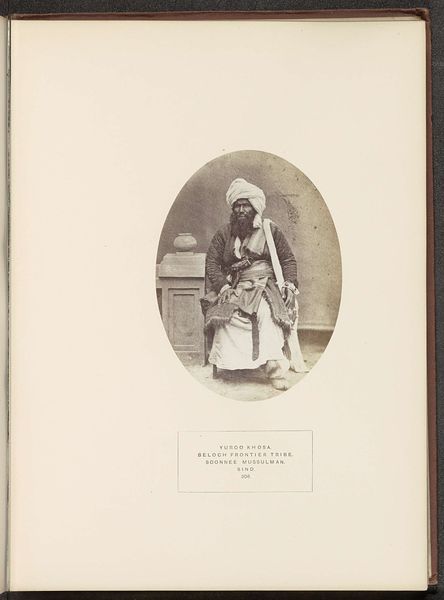

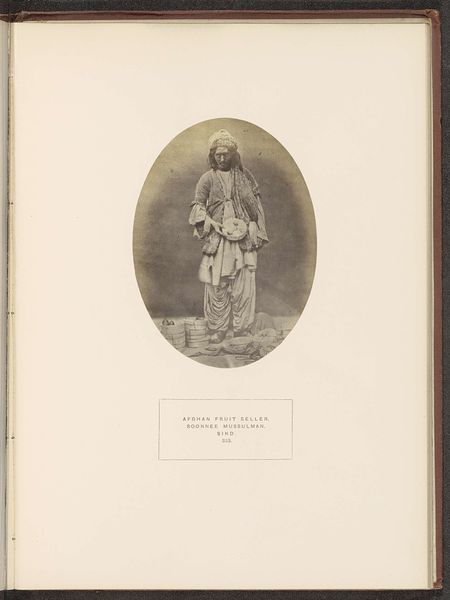

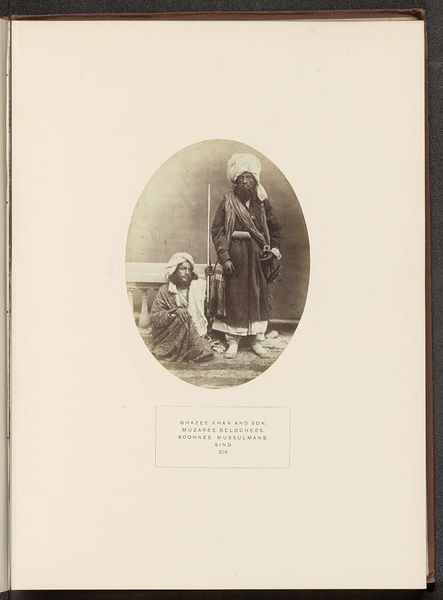

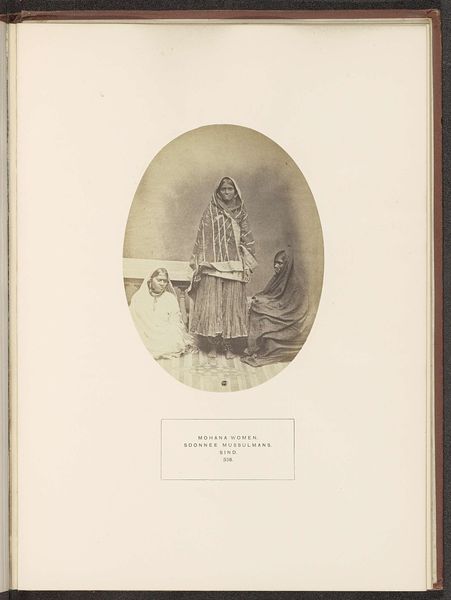

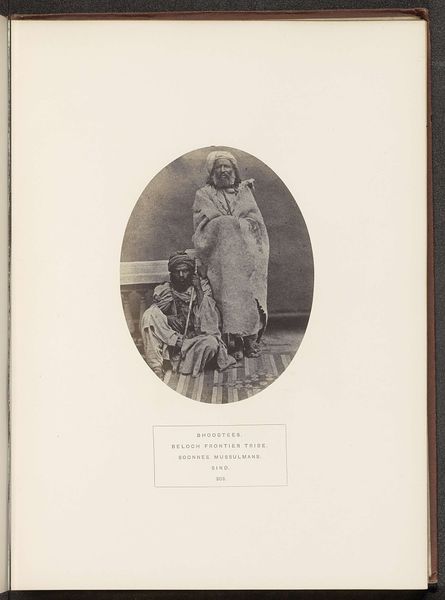

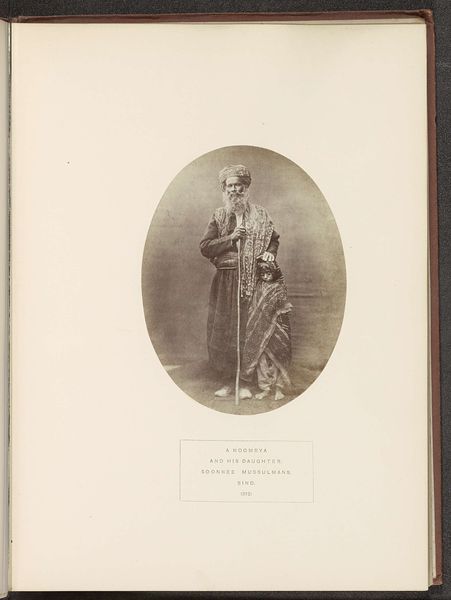

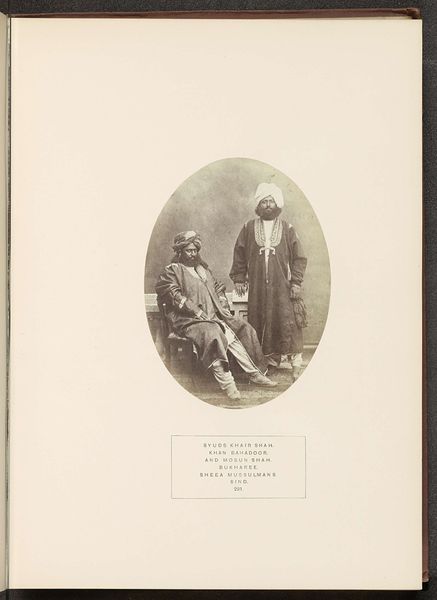

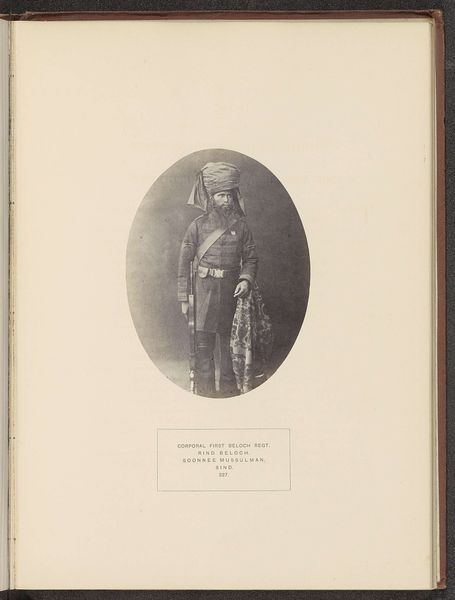

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 175 mm, width 128 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This portrait immediately strikes me as both captivating and deeply unsettling. There’s a sense of... exploitation lurking beneath the surface, would you agree? Editor: Perhaps, but before we delve into that, let's give our listeners some context. The work, simply titled "Portret van een onbekende man van de Guddra-stam", meaning "Portrait of an unknown man from the Guddra tribe," is an albumen print dating back to before 1872. The photographer is Henry Charles Baskerville Tanner. Curator: The term "unknown" feels significant here. It’s part of a larger historical trend where Indigenous bodies were displayed without agency or even basic acknowledgement of their individuality, particularly when looked through the lens of orientalism. He's staged, and for what purpose? Editor: That's precisely what I find so intriguing. Tanner’s image needs to be understood within the visual culture of the 19th century, when photography became instrumental in constructing narratives about "otherness." Albums like this often served a quasi-ethnographic function for colonial administrations. The politics of the image here hinge on the power dynamics inherent in this kind of representation. Who is looking at whom, and why? Curator: Absolutely. The composition itself frames him as exotic, even passive. His clothing, the fabric draped next to him – all curated for the Western gaze, right? It becomes another artifact within the colonial project, obscuring the man's lived experience. Editor: There’s also a level of complexity that cannot be denied. While we must address its colonial undertones, Tanner’s work could be argued as presenting its subject with an air of dignity despite it all. It raises complex questions around portraiture, power and the ethics of visual representation in colonial contexts. Curator: It does. His direct gaze is somewhat defiant, forcing us to confront the historical imbalance of the encounter. Thinking critically, maybe his stance allows him at least an act of agency, of bearing witness. Editor: Ultimately, this work serves as a powerful reminder of the crucial role art institutions have in unveiling the layers behind historical representations, promoting dialogue that acknowledges their complex legacies. Curator: I concur. It is precisely this kind of dialogue that enables us to reckon with our past, interrogating whose voices were muted and seeking to amplify them in the present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.