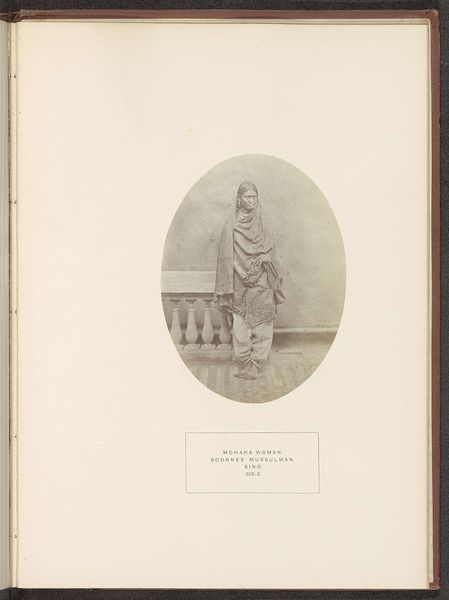

Portret van drie onbekende courtisanes van de Mohana-stam before 1872

0:00

0:00

photography

#

portrait

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

islamic-art

Dimensions: height 157 mm, width 118 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

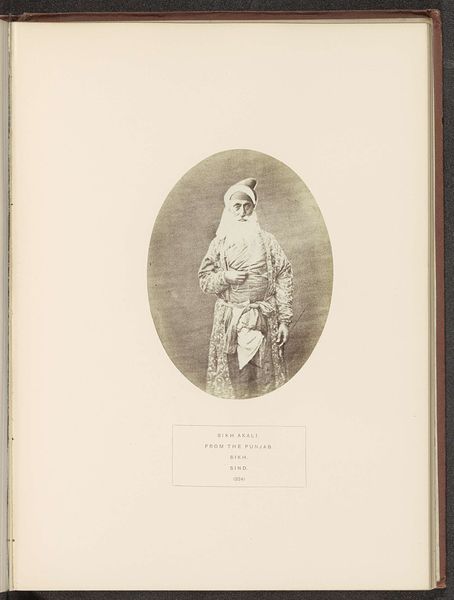

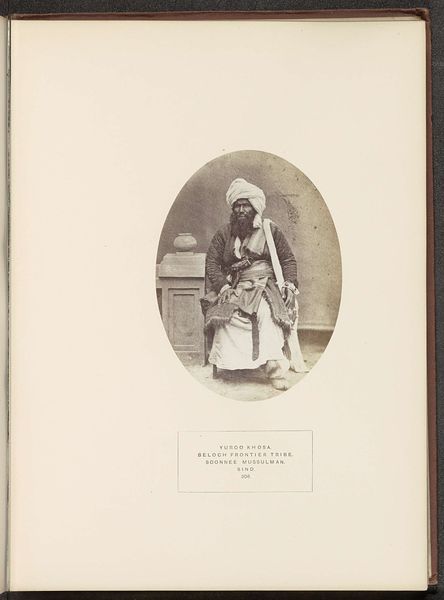

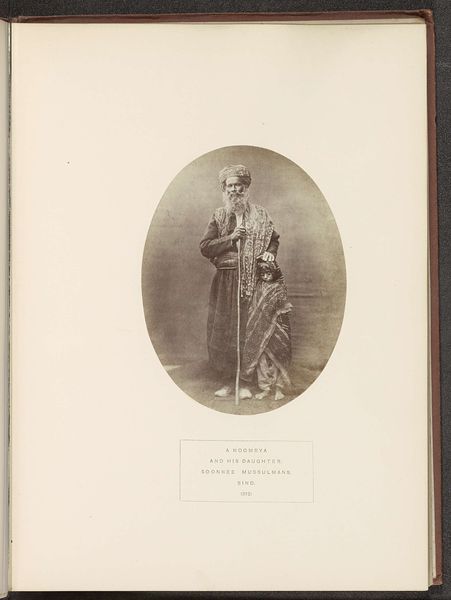

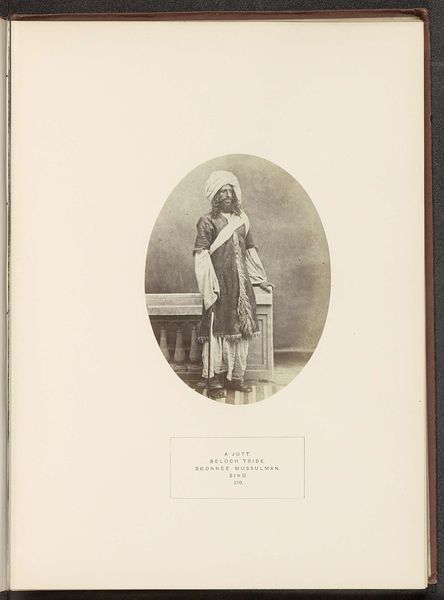

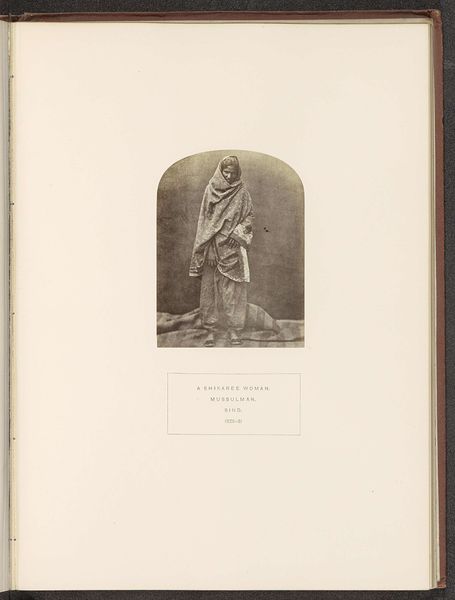

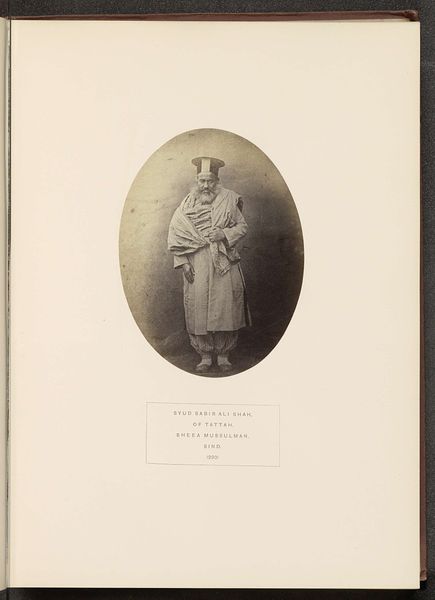

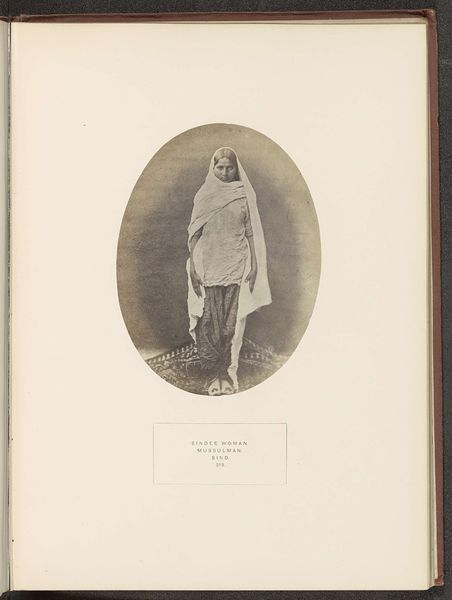

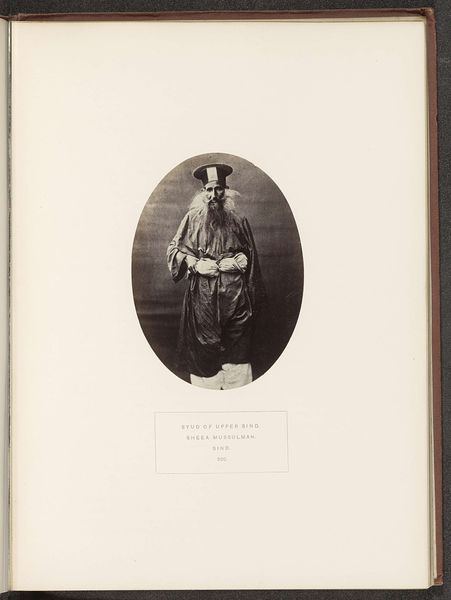

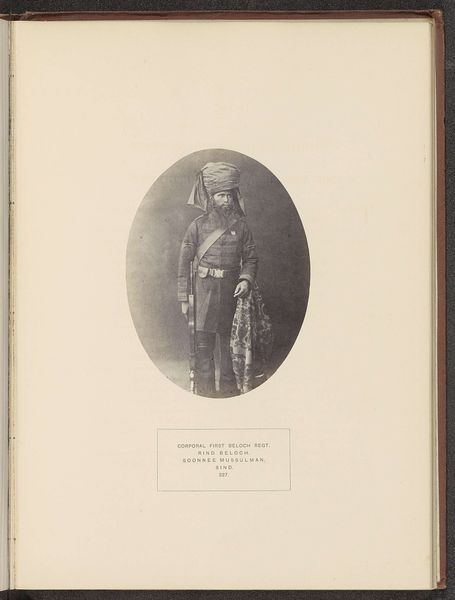

Curator: The mood here is certainly striking; a sepia-toned photographic print, almost spectral. A softness throughout makes it feel timeless, yet immediately it evokes questions of colonialism and representation. Editor: Absolutely. Let's delve into some context. What we're observing here is a work entitled "Portret van drie onbekende courtisanes van de Mohana-stam", created before 1872 by Henry Charles Baskerville Tanner. It's a fascinating artifact. Curator: Fascinating is one word for it. I’m immediately drawn to the materiality. What kind of paper, what kind of development process created these hazy, almost indistinct figures? Were these women actually rendered this way, or did the photographic process soften and exoticize them? What was Baskerville Tanner's role in all of this? Editor: Those are critical questions. Tanner was, after all, an outsider. These images participated in the broader Orientalist movement, exoticizing the "East" for Western audiences. Consider how this photography would have been viewed back in Europe—as a depiction of exoticized women but also as a visual record documenting far-flung peoples. Curator: The garments, too, catch my eye. It’s all we have in terms of physical description – layers of draped fabric obscuring the figures, creating visual interest and contributing to this exotic atmosphere. Editor: Right. And let’s not forget the label associating these women with the Mohana tribe and the designation "Soonnee Mussulmans", emphasizing religious identity alongside ethnicity. The captioning is itself a powerful act of defining the other, influencing its reception, as this portrait becomes a kind of ethnographic document to Western eyes. It plays into pre-existing perceptions, and likely prejudices. Curator: I am interested in how photography’s unique attributes -- its indexical relationship with the "real"-- contributed to solidifying and concretizing cultural perceptions. After all, a painting would elicit less assumptions about "accuracy" from the audience than photography did and does! I keep pondering how labor practices were organized surrounding these colonial photographic ventures. Editor: I agree entirely. The photographic endeavor had a distinct, documentarian tone, that helped the imperial social machine perpetuate. I find the very existence of a piece like this so powerful in illuminating the public perception of art. The ways it intersects with broader history makes the conversation never run out. Curator: Right, it really invites critical examination beyond just the surface aesthetic appeal. Thanks! Editor: My pleasure.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.