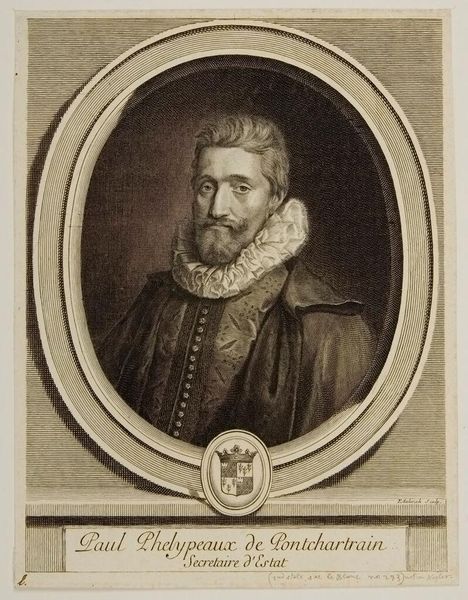

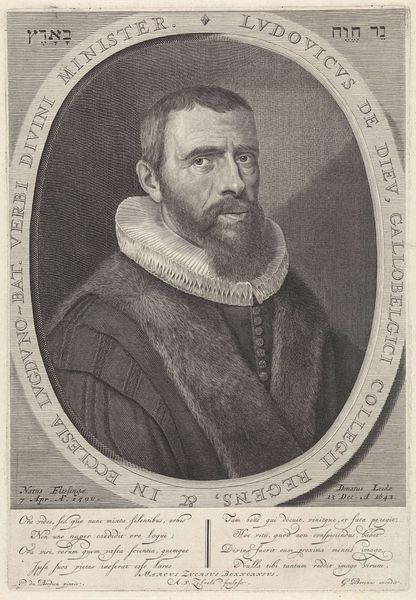

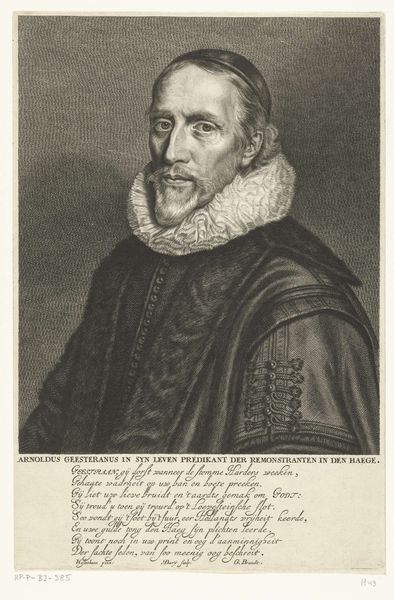

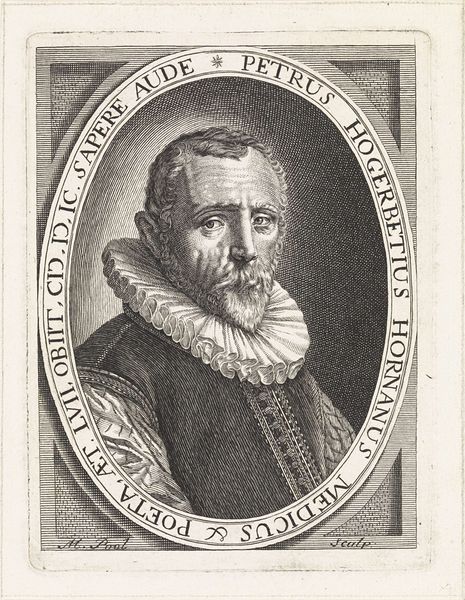

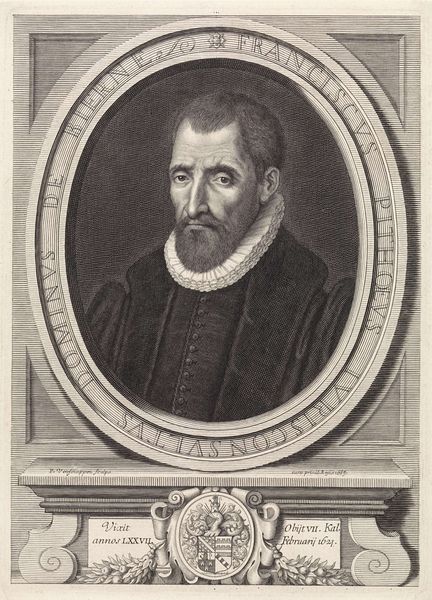

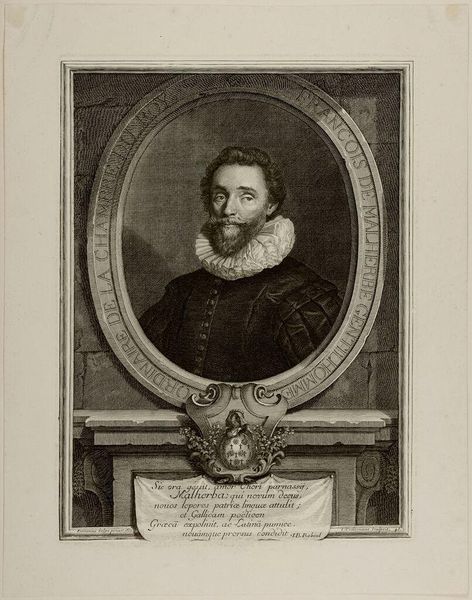

intaglio, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

intaglio

#

old engraving style

#

historical photography

#

line

#

portrait drawing

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 252 mm, width 193 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Immediately, I'm struck by the sheer *control* evident in those lines. So deliberate. Editor: And it would need to be! We are standing before Gėrard Edelinck’s engraving of Paul Phėlypeaux, a portrait made sometime between 1652 and 1707, now housed here at the Rijksmuseum. What is the first impression you get from this piece? Curator: Honestly? Austerity. It feels incredibly formal, stiff even. You can tell this Paul guy, with his giant lace collar, was someone of great importance, Secretary of State no less! Everything seems so meticulously placed. Editor: Meticulous is right. Edelinck was a master of intaglio, cutting into that metal plate with such precision. I find myself considering the labor. Imagine the hours spent just on that ruff, the way it frames his face. Curator: True, there’s a certain dedication... a craft. But I can't help but think of the man, Phélypeaux himself. His gaze... distant, thoughtful, a little sad? It goes beyond mere likeness. He seems burdened by something, some grand historical weight, as you put it, a bit tragic and strangely endearing, isn’t it? Editor: I think more about the engraver, Edelinck, how he translates flesh and fabric into lines and cross-hatching. Consider the baroque era’s obsession with ornamentation – the labor is a visible symbol of wealth. Look at how the lines coalesce, a whole universe conjured by the tools in an artist’s hand! Curator: Well said. It brings me to wonder: if this engraving speaks of a certain era’s priorities and even obsessions, perhaps art itself can hold up a mirror, not just to powerful figures, but to a whole era and maybe the ones to come. Editor: And perhaps that mirror reflects less about "great men" and more about the conditions under which images, and ultimately histories, are made.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.