print, metal, ink, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

metal

#

old engraving style

#

portrait reference

#

ink

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

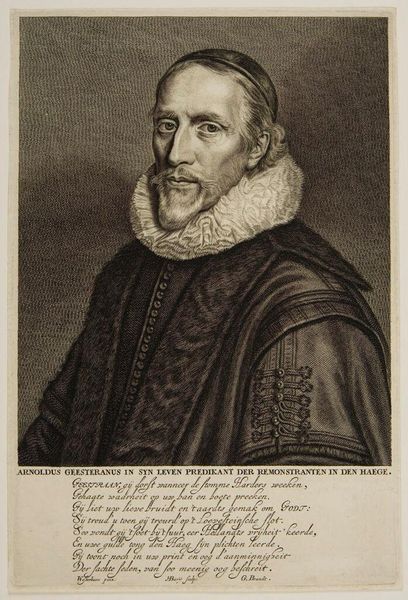

Dimensions: height 293 mm, width 195 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

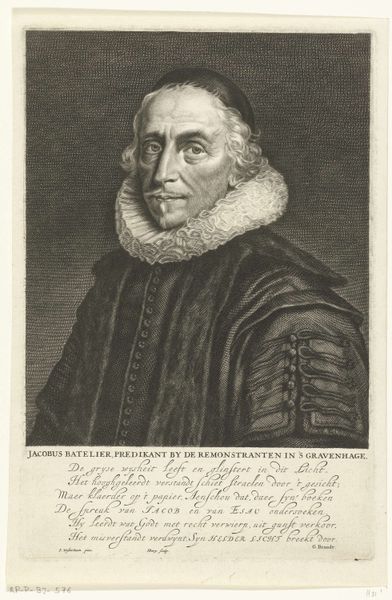

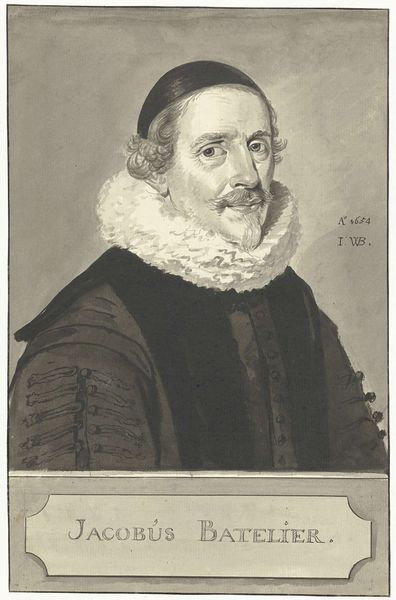

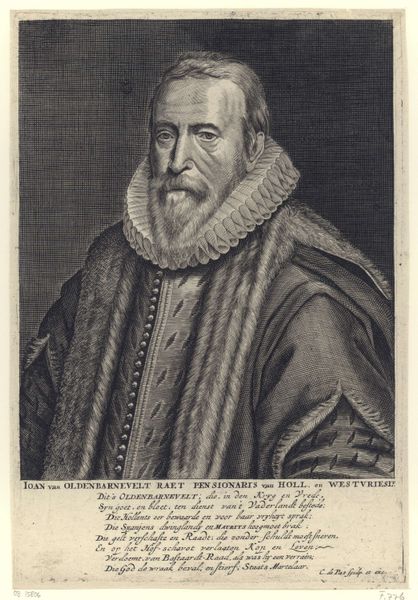

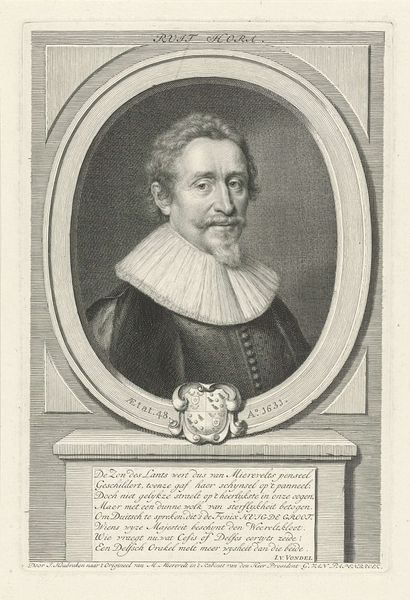

Editor: Here we have "Portret van Arnoldus Geesteranus," an engraving by Hendrik Bary, sometime between 1657 and 1707, housed at the Rijksmuseum. It's incredibly detailed. I'm struck by the textures—especially the ruff collar and the almost severe expression of the subject. What aspects of this work stand out to you? Curator: The most interesting part of this work for me is its role as a public image in the context of the Dutch Golden Age. Portraiture in this period wasn't just about capturing likeness; it was about constructing and projecting identity, especially within religious and political circles. The inscription at the bottom gives us key context. Knowing Geesteranus was a Remonstrant preacher tells us a great deal. Editor: So, the choice to create and distribute this engraving would have been a deliberate statement? Curator: Exactly. Think about the printing press as a form of social media in its day. Engravings like these circulated widely, shaping public opinion. It allowed Geesteranus to broadcast his image and, by extension, the values and beliefs of the Remonstrant movement. Do you notice anything about his clothing and overall presentation? Editor: It's quite formal, almost somber. The dark coat and the meticulous ruff suggest a man of importance, but also a certain restraint. Curator: Precisely. Restraint, seriousness, piety – these were all virtues prized in certain segments of Dutch society at the time, and communicating those ideals was essential in that time's politics of imagery. In what ways might his followers have received this engraving? Editor: It provided a visual representation of their leader. A symbol of their beliefs in a time of religious conflict. This would serve as propaganda in a way. I had never thought about art serving this specific purpose before. Curator: Seeing it as a constructed public image shifts our understanding of it from a simple portrait to a powerful tool of communication and persuasion. I never considered engravings to be propaganda. It seems clear in retrospect.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.