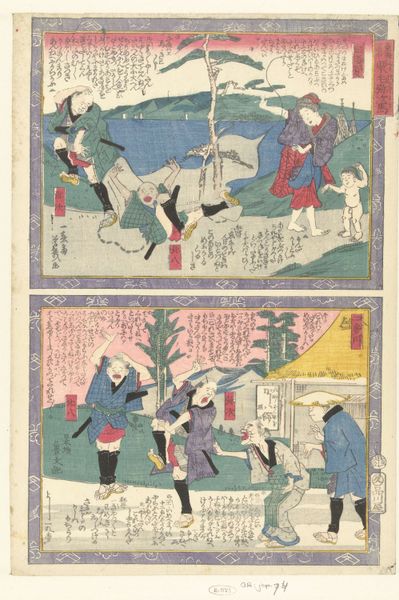

Dimensions: 7 1/4 x 9 3/4 in. (18.4 x 24.8 cm) (image, sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

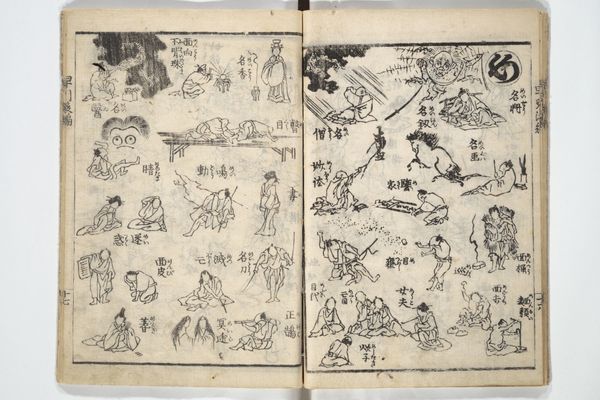

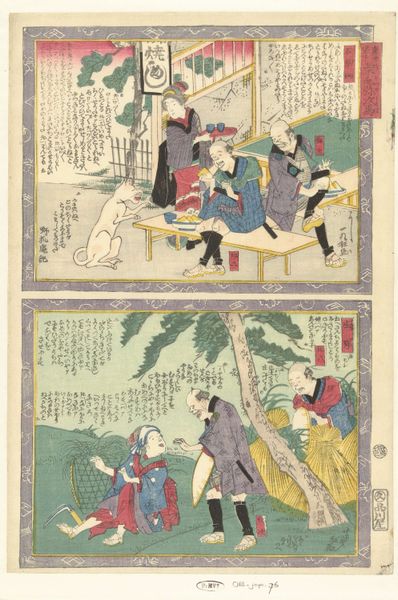

Curator: Here we have "New Year's Gift for Children," a late 19th-century woodblock print by Kuretakedō Sanboku. My first impression is its ordered chaos: twelve miniature worlds contained in neat rectangles. Editor: Exactly. It’s the sheer quantity of detail, isn't it? It feels like a material catalog of everyday life in the 1870s. Look at the processes depicted. Curator: You're right. There's such a breadth of activity represented, like workers making rice cakes, people traveling with donkeys, and kids playing—framed within scenes of landscapes that feel imbued with an Edo-period sentimentality. These all served didactic purposes. The artist likely meant to both celebrate the upcoming New Year while illustrating essential aspects of Japanese culture, thus reinforcing important elements of life. Editor: Right, because these images acted as visual texts. We're not simply viewing genre scenes. We're encountering social mores encoded into wood and ink. Observe the image in the upper right: someone is swinging a bat and wearing an eye cover; these details probably reflect not just games, but potentially wider rituals around play, work, or identity formation for the youth that the art would serve. Curator: It really encapsulates so much, and the woodblock print, as a replicable medium, reflects the expansion of knowledge in a pre-digital world. It suggests how images became more readily accessible to a wider audience beyond traditional elite circles. Also, consider the ink; you know that traditional sumi ink had a complex history. Editor: Indeed. This piece exists within the lineage of *ukiyo-e*, popular art intended for mass consumption. Thinking intersectionally, who had access to this? What labor produced it? How were these representations shaped by dominant ideologies? The seemingly simple genre painting then becomes a mirror reflecting complex power relations within Japanese society. Curator: I suppose, too, it's fascinating how relevant it remains, despite all the change; in effect, these prints are blueprints for preserving Japanese custom and, of course, marketing those ideals. Editor: Yes, these squares present not just nostalgic slices of life, but curated messages meant to instill societal values in a youthful populace as well. They have that duality: nostalgic but purposeful, artistic but manufactured for an occasion.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.