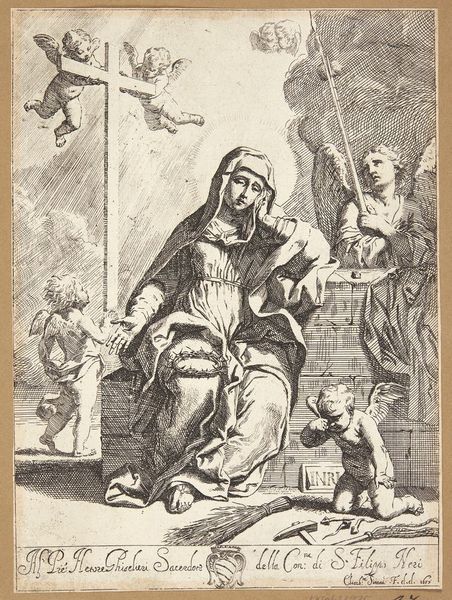

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

pen illustration

#

figuration

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 220 mm, width 197 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving, crafted around 1530 by an anonymous artist, is titled "Henoch met zijn vrouw en kinderen"—Enoch with his wife and children. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: It's remarkably lively, especially for an engraving of that era. The figures of the children have such a tactile quality. There's an almost chaotic energy despite the somber expressions of the adults. Curator: Absolutely. Consider the role of family portraits within the social and religious contexts of the Northern Renaissance. Works like this weren’t simply domestic scenes; they actively communicated a family's identity and status in the world, and especially their place in the religious world. Editor: It does seem intent on portraying a righteous, God-fearing family, doesn't it? Yet there’s this sense of contained anxiety that ripples through it. I wonder how intentional that contrast might be? And who this Henoch was meant to represent at the time? Curator: The Old Testament figure Enoch was indeed a patriarchal exemplar. Now, think about the politics of image making in the 16th century, particularly within domestic spaces. Who had access to this engraving? How would its presence in the home shape societal notions around family piety? And how are women represented? The mother here looks less joyous. Editor: Exactly! There’s a definite separation—almost an imposed one—between her role as a caregiver and her husband’s presumed authority and connection to the divine. The weight of societal expectation seems visually embedded in her form, wouldn't you say? Curator: It underscores the prevailing patriarchal norms where women are defined almost exclusively within domestic roles and the reproduction of the family line. That these roles are portrayed with so much care is part of the dynamic the piece invites to interpretation. Editor: And it prompts a discussion about the artwork’s original viewer—whose perspective are we meant to adopt? It leaves me pondering the lived experiences of women during this time period, so drastically different, yet, on a patriarchal level, perhaps, also connected to current power structures. Curator: Exactly. By understanding these power dynamics, and their visual representation at the time, we can appreciate the print as both an object reflecting a specific culture and historical moment, but also, importantly, we get a view of ourselves. Editor: An exercise in perspective—both backward and forward. Fascinating!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.