weaving, textile, guilding

#

asian-art

#

weaving

#

textile

#

guilding

#

figuration

#

geometric

#

islamic-art

#

history-painting

#

decorative-art

#

miniature

Dimensions: 26.6 × 26.2 cm (10 1/2 × 10 3/8 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

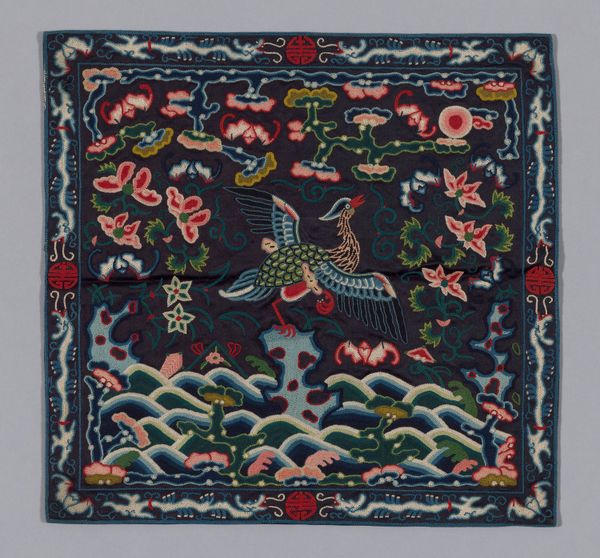

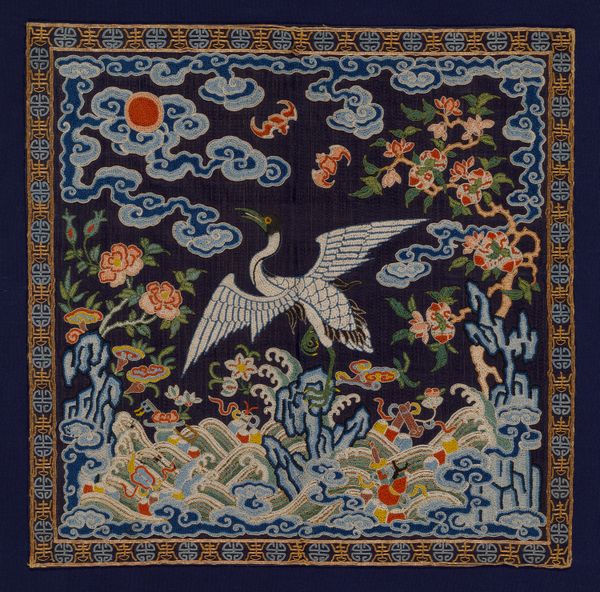

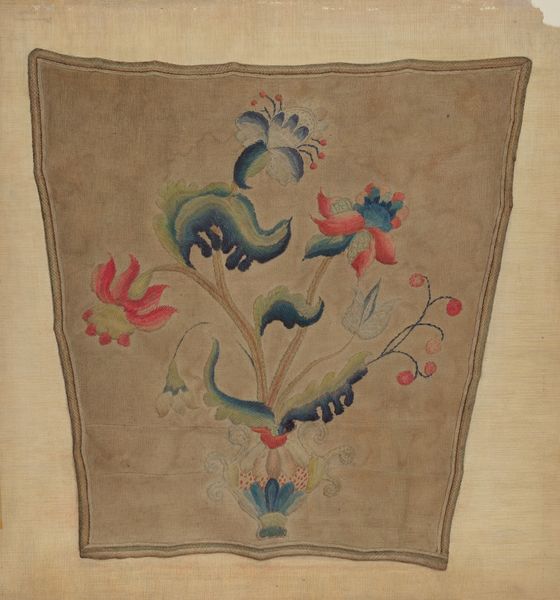

Curator: The saturated colours are the first thing I notice; they feel potent. Editor: This is a Buzi, or rank badge, dating possibly from the Qing Dynasty, which lasted from 1644 to 1911. These textiles were made in sets, intended to be sewn onto court robes, communicating the rank of the wearer. The Chicago Art Institute holds this example, and the medium involves weaving and gilding. Curator: Visually, this strikes me as a world in miniature. A stylized tiger, positioned above churning waves, set against a sky with swirling clouds and a red sun. There's a distinct symbolic stratification. The water suggests the primordial chaos from which the earth emerged, with the tiger representing earthly power, ascending to the heavens. Editor: Yes, and let's delve deeper into the imagery. The tiger itself, in this context, most likely denoted military rank. This patch speaks volumes about the structured hierarchy of the Qing Dynasty. One’s place in society was visually declared through such symbols. Curator: You're right, these aren't mere decorations but highly regulated insignias of power. Looking closely, one can appreciate the detail: the way the clouds curl, and the small flames lick from the tiger's body! Are those Buddhist emblems among the waves as well? Editor: Indeed, Buddhist imagery would not be unexpected. Rank badges were an expression of both state power and the emperor's personal taste or belief system. The degree to which the emperor's faith found expression would, naturally, shift through history. But you're pointing at the tensions these objects embodied. Curator: To think such a small square could tell such a detailed story. The imagery speaks of status and also implies deeper metaphysical levels! Editor: Absolutely, the Buzi serves as a fascinating lens to view social order, artistic expression, and belief systems within Qing Dynasty China. It encourages us to consider how societies create meaning through visual symbols.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.