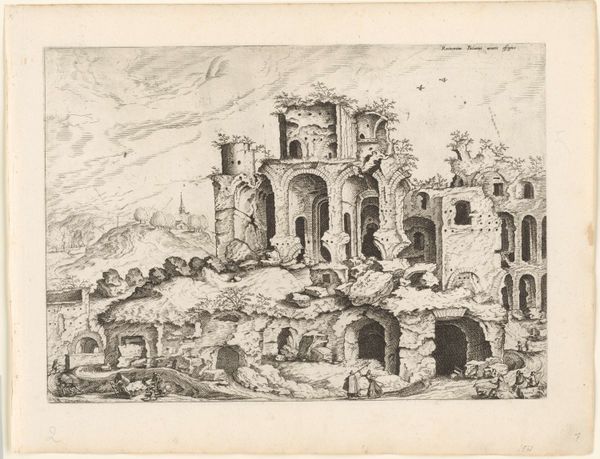

Massive Ruins with Many Figures in the Foreground from the series Roman Ruins and Buildings 1562

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: Sheet: 6 15/16 × 9 3/4 in. (17.7 × 24.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This is “Massive Ruins with Many Figures in the Foreground from the series Roman Ruins and Buildings,” an engraving dating back to 1562, credited to Johannes van Doetecum I. Editor: It’s intensely detailed. So much line work! And yet, there’s something delicate about it, almost fragile. The way the ruins are overtaken by nature is captivating. Curator: It certainly speaks to the passage of time, doesn't it? Ruins like these were potent symbols in the 16th century. They represented not just the physical remnants of ancient civilizations, but also the cyclical nature of power and the transience of human achievements. Editor: Transience, yes! Look at the material reality, though. An engraving requires careful labor. Someone had to meticulously carve these lines into a metal plate, repeatedly inking and pressing it to transfer the image. That act feels almost defiant in the face of inevitable decay. Curator: And who was this "someone?" Van Doetecum’s workshop produced prints for a wide audience. These images circulated as both artistic works and as visual records. Prints like these informed how people imagined Rome and its history. The engraving aesthetic also added a layer of classicism, shaping perception. Editor: The social element extends further, right? Prints become accessible artifacts, democratic depictions of ancient structures previously known mostly to a privileged class of travelers. This image flattens and packages, commodifies really, a cultural narrative to wider consumers. Curator: That is undeniable, plus consider how this circulation perpetuated ideas, intentionally or unintentionally. The visual choices Van Doetecum made - composition, tone, scale - influenced what and how audiences understood Roman antiquity. Was it inspiration, regret, or just information? Editor: The layers of labor—the engraver, the people implied by these “massive ruins,” plus all the implications of circulation, consumption, all leading us, the contemporary viewer to further participate by absorbing these embedded and multiple interactions with these ruined stones…it’s astonishing. Curator: Astonishing, yes. Thinking about art in its social and historical context makes even a simple print a powerful mirror. Editor: And understanding the making expands it to understand the social landscape in both material and labor conditions that have produced and sustained the image.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.