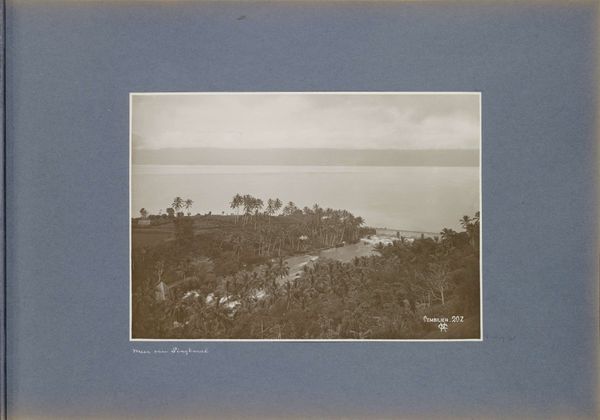

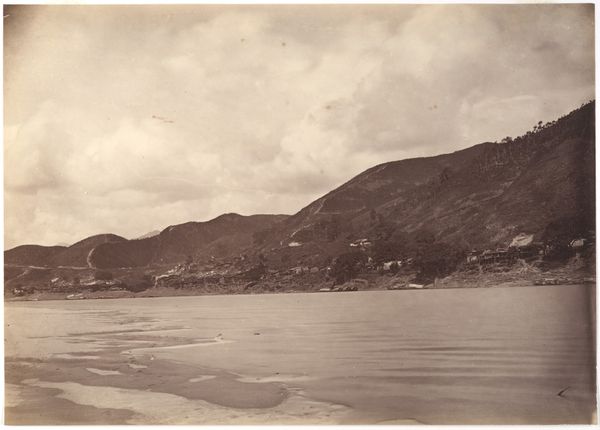

Palmenkust gezien vanuit de lucht, vermoedelijk in Nederlands-Indië c. 1930 - 1940

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

photography

#

landscape

#

photography

#

realism

Dimensions: height 272 mm, width 395 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

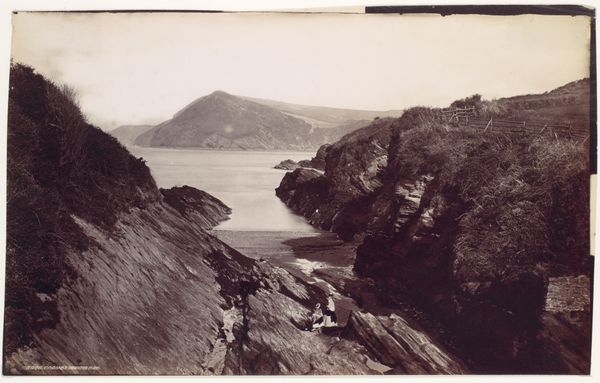

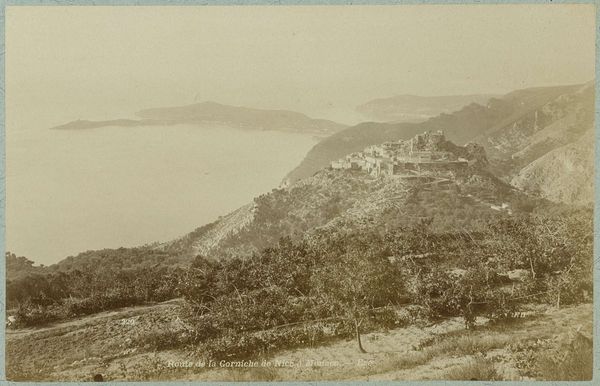

Curator: This black and white photograph, whose title translates to "Palm Coast Seen From Above, presumably in the Dutch Indies", captures a coastline sometime between 1930 and 1940. Its creator remains unknown. Editor: My first impression is one of quiet industry. It’s a document, almost clinical, yet the array of textures – water, rock, foliage – pull you in. Curator: Yes, it speaks of its time, doesn't it? Beyond the realism, I see colonial symbolism—the cultivated paradise, a land both exotic and tamed by the implied European presence. Editor: Precisely, it presents that era through photographic means: silver gelatin perhaps, highlighting light manipulation in revealing this landscape and inviting speculation about photographic processes of the period. The tonal range hints at a deliberate emphasis on texture too, rather than atmosphere. Curator: Absolutely. Consider the visual language: the strategic high vantage point signifies power. Even the palms, icons of leisure, seem almost regimented. Is that a car I spot in the top right? It is subtle, but seems to denote human dominance and control in an untamed tropical setting. Editor: Yes, and that hints towards an emerging tourist industry and infrastructure disrupting and encroaching this ‘natural’ scenery, and with that raises questions around consumption, mobility, and resource management within the colonial setting of that time. It becomes less about untouched nature and more a study in land use. Curator: It prompts reflection on the act of viewing. Are we positioned as detached observers, or are we implicated in this power dynamic through the very act of looking? The visual symbol of colonialism’s legacy invites critical engagement. Editor: I see what you mean, the act of looking itself becomes part of the artwork's context. Overall, what starts as an attractive scene pushes to question and consider colonial imprint upon landscape, people and even the artwork’s own production. Curator: Exactly, and that realization perhaps alters our perception and appreciation of the whole image, from surface to symbol. Editor: It certainly shifts our engagement, from a scenic image to a photograph laden with colonial associations, both material and symbolic.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.