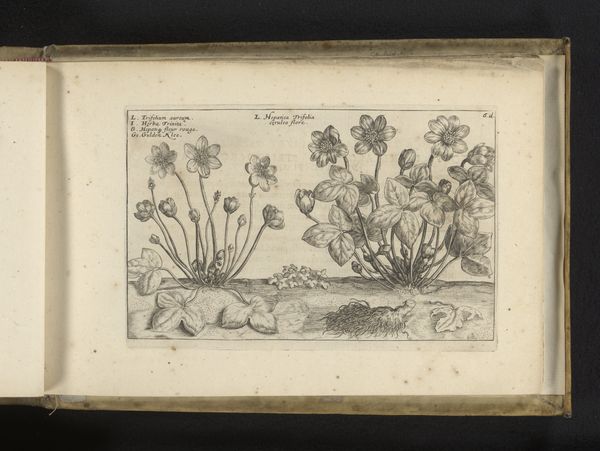

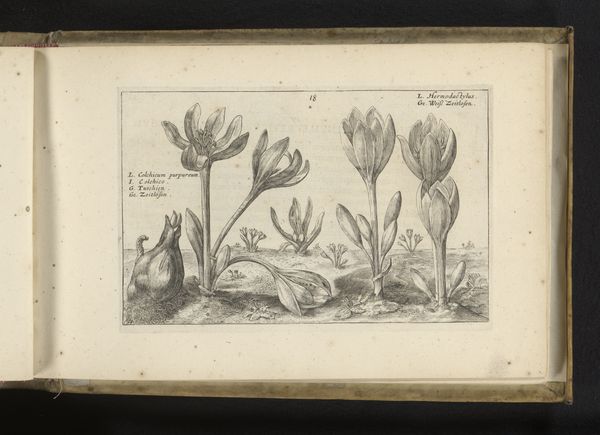

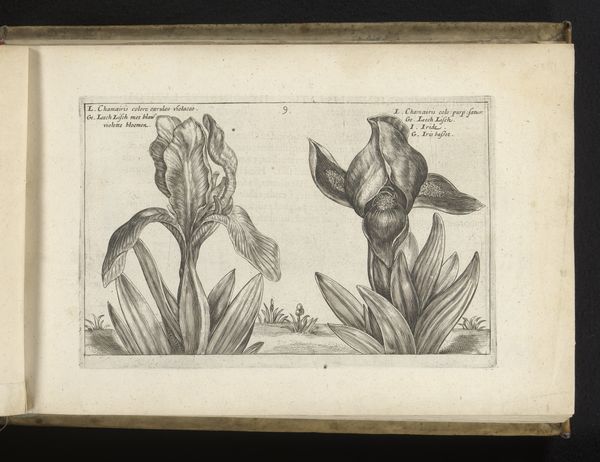

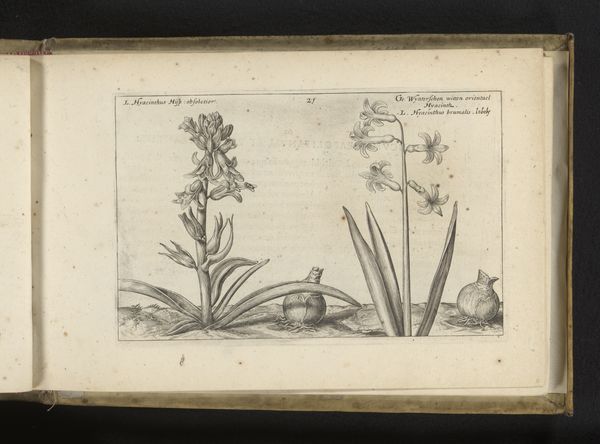

drawing, print, paper, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

flower

#

paper

#

ink

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 135 mm, width 205 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

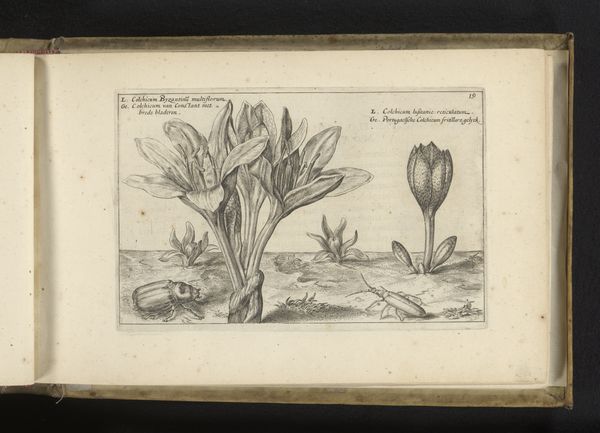

Curator: This engraving, "Twee herfstbloeiende soorten Colchicum," or "Two Autumn-Flowering Colchicum Species," was created by Crispijn van de Passe (II) in 1617. Editor: There’s an intriguing starkness to it, a blend of delicacy and almost scientific precision in how these plants are rendered. What really catches my eye is how tactile it feels, especially the detail given to the earth surrounding the blooms. Curator: The Colchicum flower held varied symbolic meanings in the 17th century. Though admired for their beauty, their association with autumn, a time of decay, made them symbols of mortality and transience. These botanical illustrations often found their way into emblem books, conveying moral lessons about life's fleeting nature. Considering this context, these particular representations engage in complex negotiations of science and societal narratives around women in Northern Renaissance Europe. Editor: Absolutely, and that materiality resonates deeply with the societal moment, right? Consider the engraver’s labor—each line, each dot etched into the plate, is a deliberate act of making visible. These materials--ink, paper, and metal--aren't neutral; they are testaments to the skill and technology of the time and shaped by early capitalist print culture. Were prints such as this aimed at wealthy landowners eager to enhance their estates? Curator: I agree; their mode of production absolutely intersects with its circulation among wealthy patrons. Van de Passe's illustrations appear rooted in early modern studies of natural philosophy and medicine, often used within aristocratic circles as a way of expressing intellectual virtuosity, in an effort to assert agency and control within hierarchical settings. Editor: Precisely. It brings into question our assumptions of art versus craft in its mode of production and consumption. How would the engraver have thought about labor when creating such things, or those who owned this print? It all adds to its meaning. Curator: This is why analyzing these images beyond the pure aesthetics is so essential. Approaching them as sites of cultural meaning offers an avenue into grasping not only the botanist's or artist’s perspective but how scientific and creative endeavors in turn informed wider social understandings of gender roles in that era. Editor: That reframing gives such weight to this delicate image. I won’t be able to look at another botanical print without asking about who created it and why it was made and its social life in printmaking, production, labor, and exchange.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.