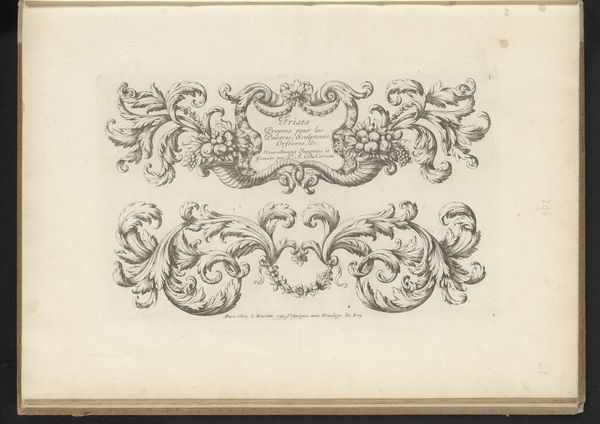

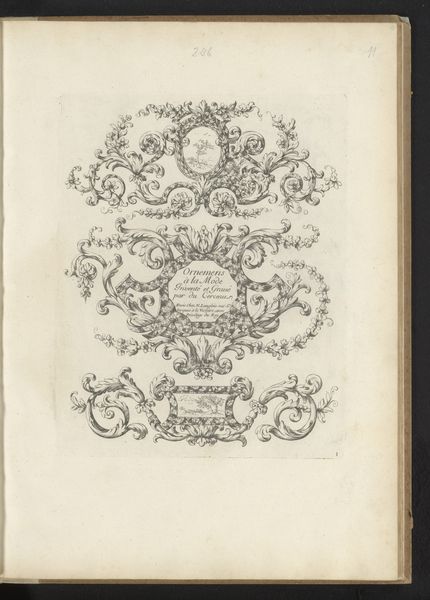

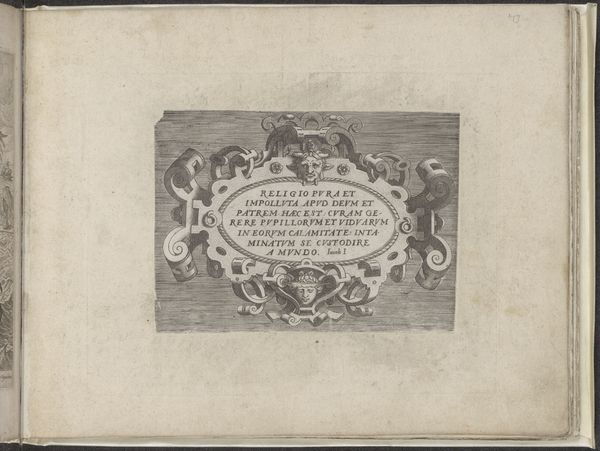

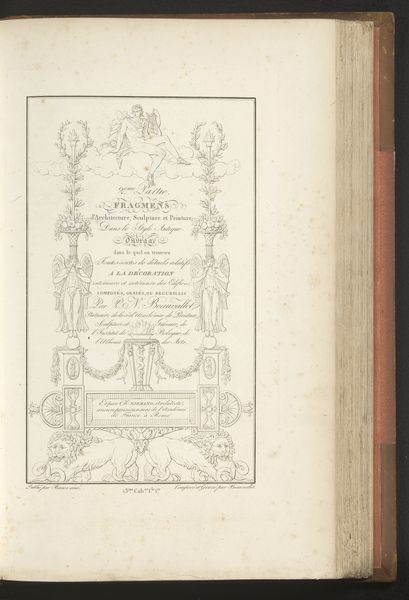

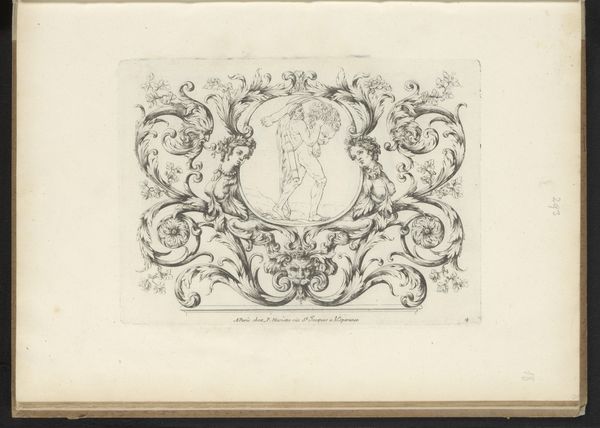

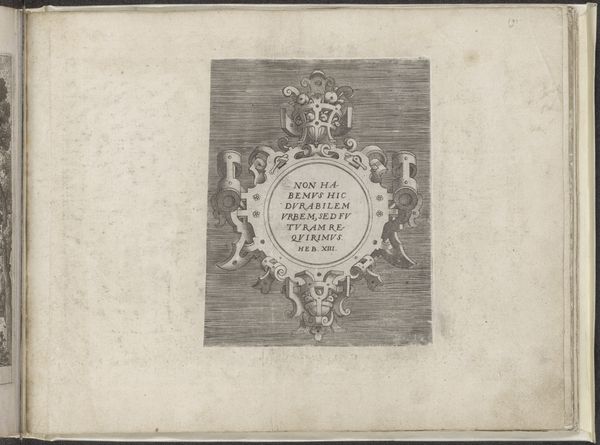

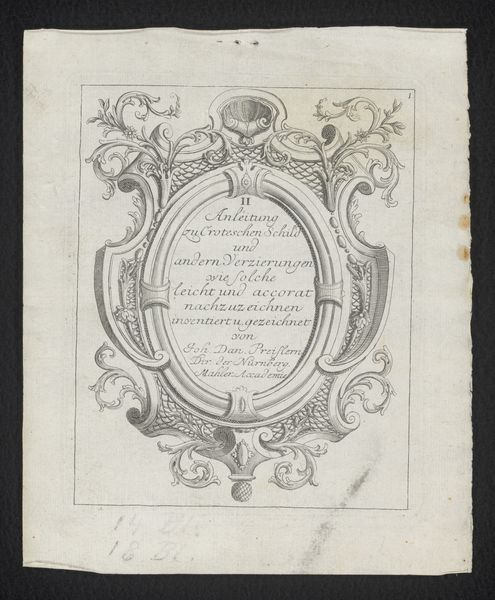

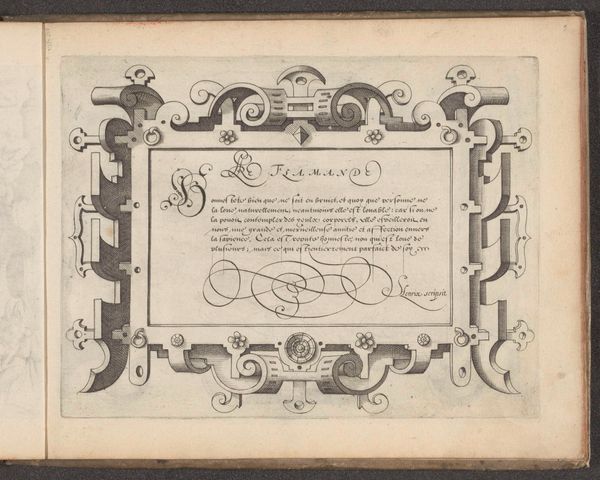

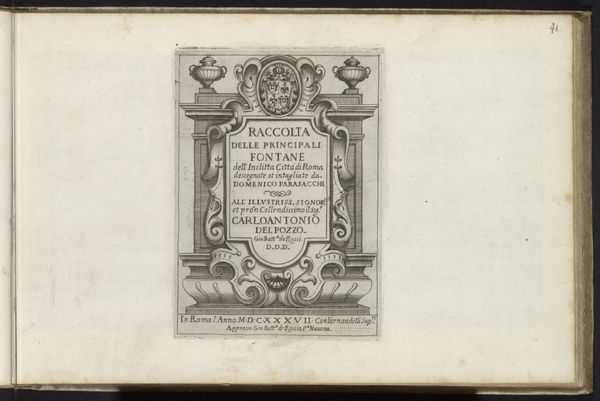

drawing, ornament, print, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

ornament

#

baroque

# print

#

ink

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 259 mm, width 189 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Paul Androuet Ducerceau’s “Titelprent met saters en vrouwelijke hermen,” created sometime between 1660 and 1690. It’s a drawing using ink and engraving, currently held at the Rijksmuseum. I find the detailed linework and fantastical figures captivating. What catches your eye? Curator: What immediately interests me is its function as an ornament. It is important to recognize the print *as* an object of material culture, designed for a specific market. Who was buying these kinds of ornamental prints in the late 17th century, and how did they use them? Editor: So, it wasn't necessarily seen as high art, but more as a functional design? Curator: Exactly. Think about the labor involved. Engraving was a skilled craft, and this print was likely intended as a source for other artisans – furniture makers, tapestry weavers – who would incorporate these designs into their own products. The "Aux Privilege du Roy" indicates it was officially sanctioned and protected against unauthorized reproduction – pointing to the value placed on this sort of design knowledge. How do you see the print speaking to consumer culture at that time? Editor: I hadn’t considered the mass production angle, that it could be disseminated to many different craftspeople! So, the value wasn’t necessarily in the original artwork itself, but in its ability to be reproduced and influence other works. Curator: Precisely! Considering it this way changes our entire perspective on the print and the artistic practices of the period, showing how art was intricately linked to the burgeoning markets of design and decoration. Editor: This really broadened my understanding of its cultural context. Thank you!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.