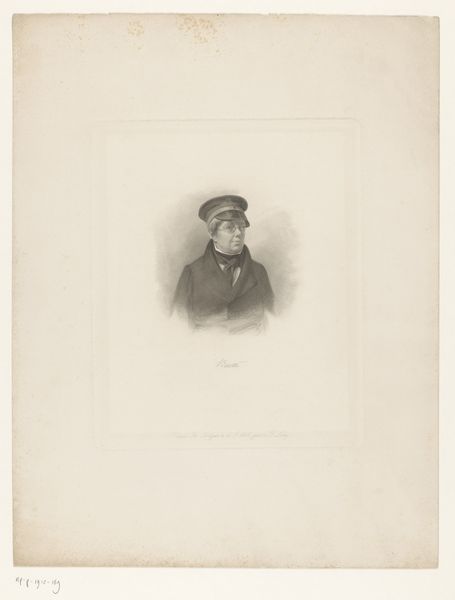

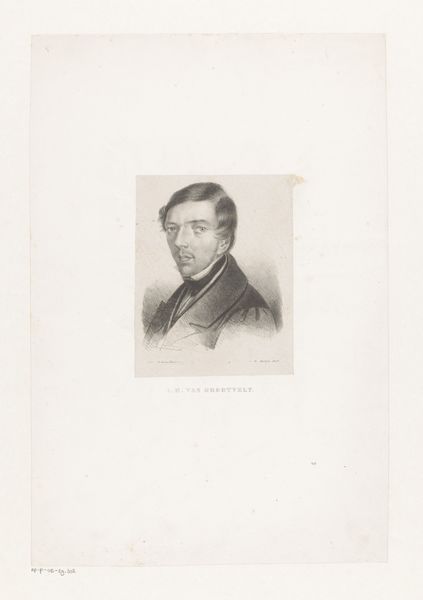

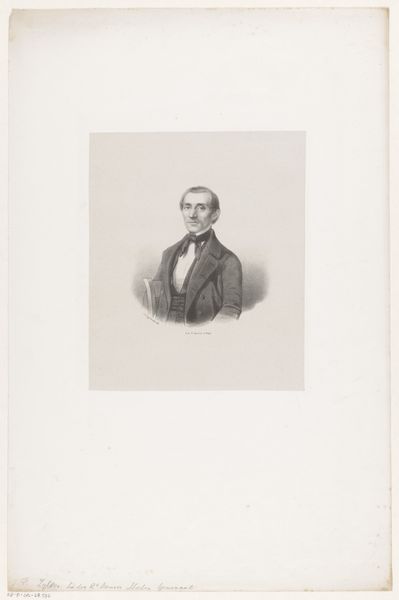

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

pencil drawing

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 245 mm, width 156 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

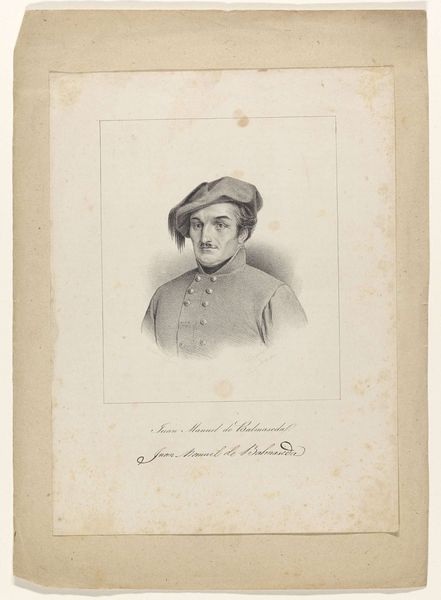

Curator: This print presents a portrait of Louis Brune, realized sometime between 1827 and 1843, attributed to Ephraïm Conquy. It’s executed through engraving, lending a certain crispness to the depiction. Editor: My immediate impression is a quiet intensity. The subject’s gaze is direct, yet there's also a hint of melancholy in his expression, heightened by the monochromatic palette. Curator: Considering the timeframe, portrait engravings like these served a vital role. They helped disseminate imagery, allowing likenesses of prominent individuals to circulate within society and reinforce social hierarchies. Editor: Absolutely. You can almost read it as a form of early social media— curated depictions crafted for public consumption. How do we think his position in society is constructed and then conveyed in this work? The sitter's attire and decorations certainly speaks of status. Curator: Indeed. His uniform suggests military or governmental service, reinforced by the decorations he wears. These details acted as visual cues, communicating his position and achievements to a wide audience and contributing to a construction of national identity. Editor: I'm particularly drawn to the artist's treatment of texture – you can almost feel the nap of his cap. It's such a controlled medium, yet within that constraint, the artist achieves a striking sense of realism. Curator: And it underscores the power of printmaking as a democratic medium, capable of representing power and privilege to an expanding public. It also prompts us to consider who had access to these images and how that access might reflect the prevailing social inequalities. Editor: It really allows one to consider art's relationship with historical context. The way artists then and now used realism to convey not just surface, but deep complex identity. It almost functions as a silent narrative, inviting interpretation but still subject to the gaze of history. Curator: Yes. By engaging with these types of images, we can enrich our understanding of history, while also investigating how societal structures are subtly woven into even seemingly simple images. Editor: I'll certainly think about the complex narrative implicit within what seemed to be a very clear, simply rendered piece when I leave here today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.