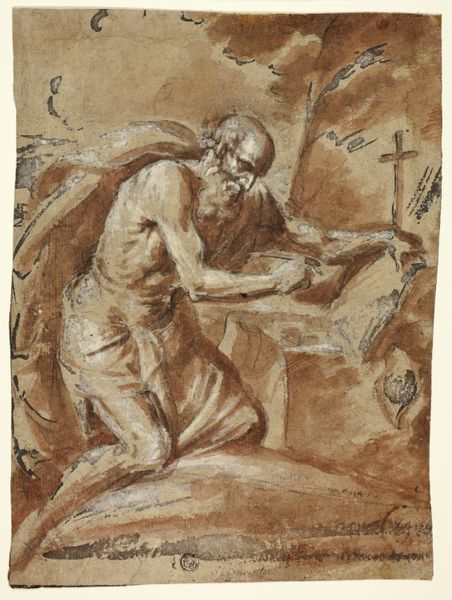

drawing, ink, pen, charcoal

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

ink

#

pen

#

portrait drawing

#

charcoal

#

history-painting

#

portrait art

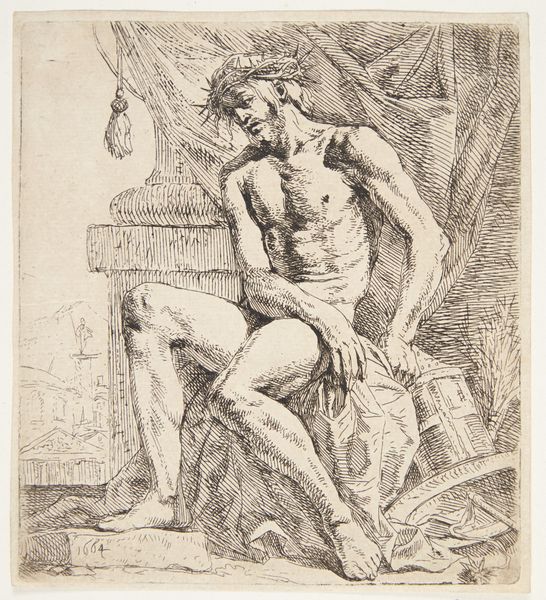

Dimensions: overall: 18.8 x 14.4 cm (7 3/8 x 5 11/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

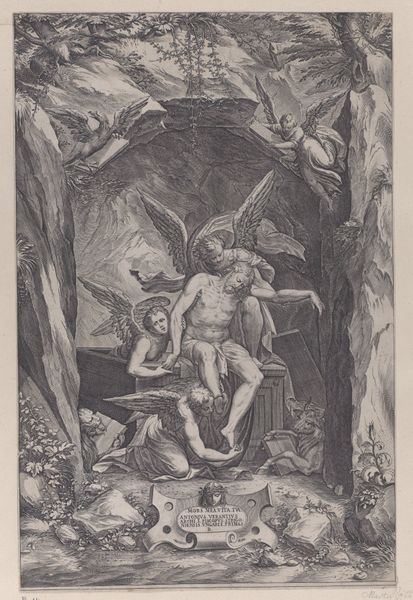

Curator: Let's turn our attention to "The Good Thief," a pen and ink drawing possibly by Karel van Mander I. Immediately, what strikes you about this piece? Editor: It’s a surprisingly intimate portrayal of suffering. The thief's resignation, and perhaps a hint of hope, seem palpable despite the medium's starkness. Curator: The use of pen and ink, especially in preparatory drawings like this, underscores the artist’s direct engagement with the subject. We see the labor—every hatch, every stroke contributed to its final appearance. This isn’t about illusion; it's about process and skillful labor in service to communicating religious doctrine. Editor: And the doctrine is essential. Situated against the distant crucifixes and watched over by those chubby cherubs, this depiction is steeped in its time. We need to consider that during the Reformation, imagery played a key role. Van Mander seems to negotiate Protestant and Catholic sensibilities about representing salvation and damnation in art. Curator: Exactly. Consider how this drawing would have served as a reference. Details, proportions, maybe even the expression, all meticulously crafted for eventual reproduction. Van Mander and his contemporaries were keen on the commerce of images, disseminating them widely for various commissions and art markets. Editor: Beyond its immediate devotional use, it speaks volumes about human suffering in its time. Is this a drawing for the elite? Or intended for broader didactic access in an age deeply divided along religious and class lines? And what about that city—a hopeful new Jerusalem or another center of corrupt power? Curator: Those are crucial points. What does this object tell us about craft? That in drawing upon existing cultural forms—visual motifs associated with salvation, justice and punishment—the artist reifies religious hierarchy, class division, the powerful economy around spiritual artworks. Editor: True, but the material simplicity of ink on paper democratizes access, symbolically leveling hierarchical access. Even now it invites reflection about power, privilege, and human capacity for compassion—even in criminals! Curator: Indeed. It shows us the artist engaging with these contradictions embedded within devotional objects meant for popular dissemination. Editor: It’s a reminder that art can be both devotional object and political statement. Its simplicity hides layers that reveal much about artistic production. Curator: Precisely. Every line of ink speaks to a rich cultural conversation of the time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.