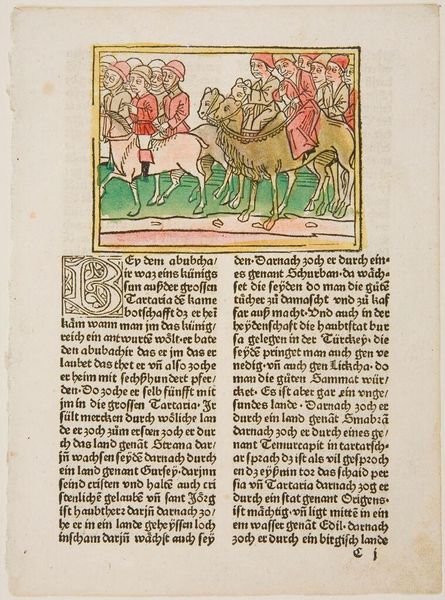

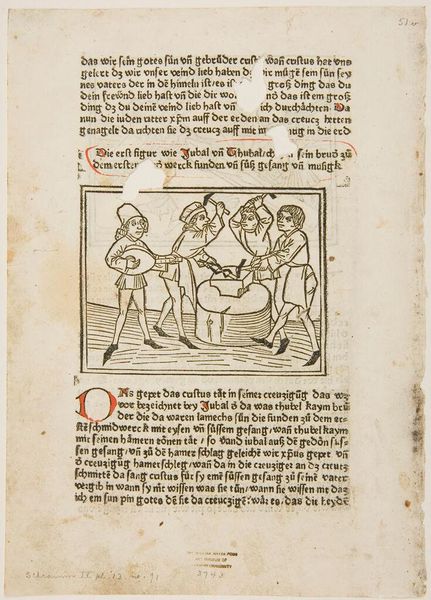

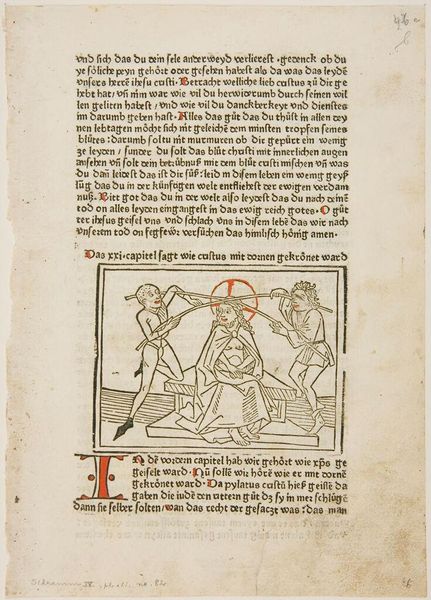

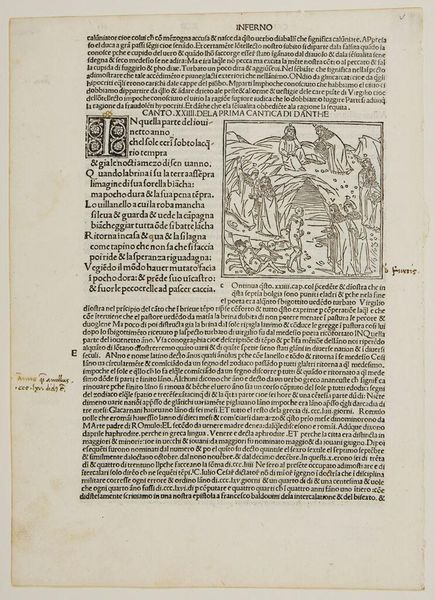

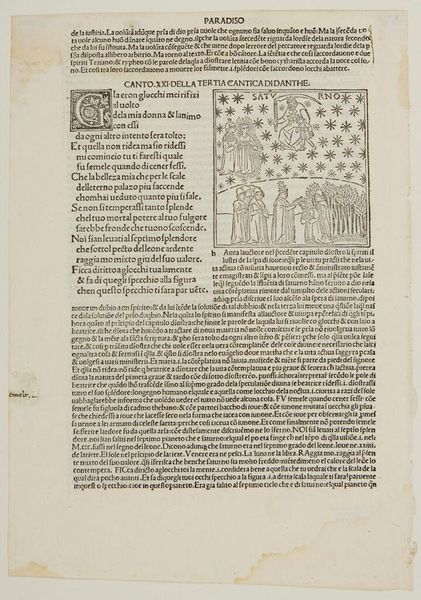

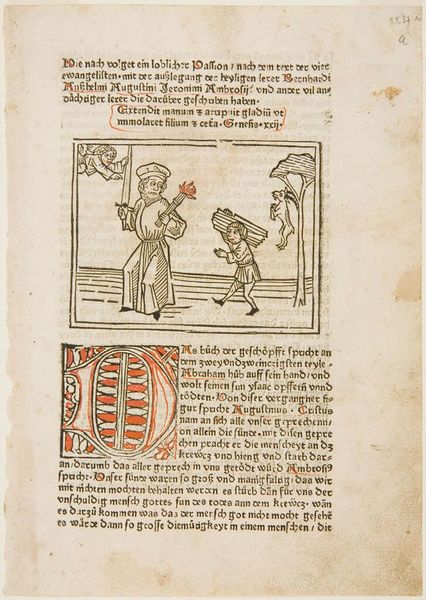

print, woodcut

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

woodcut

#

line

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

Dimensions: height 134 mm, width 88 mm, height 283 mm, width 207 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

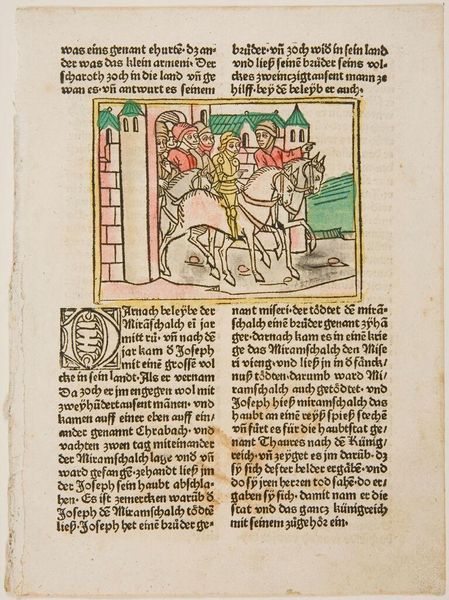

Curator: Let’s discuss this intriguing woodcut from 1499, held at the Rijksmuseum. It's titled "Keizer Constantijn de Grote te paard"—Emperor Constantine the Great on horseback. Editor: Immediately striking is the line work – it has an almost urgent quality despite depicting such a formal subject. And the colors! It's so carefully applied, lending a naive but lively touch. Curator: Absolutely. It is printed on a single sheet that also contains an extract from the history of the Roman emperors and popes, a popular and informative print medium during the Northern Renaissance. Editor: You can really feel the artist working through what an emperor even *looked* like, right? And that's coming through the specific techniques employed in production. It speaks to wider political issues in that era too—picturing authority figures became crucial in early political strategies for a more visually literate audience, making images more readily accessible. Curator: Precisely. The woodcut as a process allows for reproducibility and wide circulation of these images, but, materially speaking, wood imposes specific limits. The bold lines, the deliberate hand-coloring… each adds to the print's function as a medium through which knowledge and ideology can spread. What’s your take on the depiction itself? Editor: Well, Constantine and his retinue feel surprisingly *domesticated*. Their horses are sturdy but small, trotting over simple greenery, unlike the idealized equestrian statues of the classical era. It pulls away from established propaganda, maybe? Or simply signals something different from antiquity... Curator: The limitations and creative possibilities of working with wood may actually add to this sense. But, if the artist has any propagandistic motivation, it's to remind the viewer that images of authority—be they Roman Emperors or church figures—should be widely available to access and engage. The choice to pair the image with textual narrative reinforces the notion that art exists alongside knowledge dissemination in Northern Renaissance culture. Editor: And perhaps that tension – the formal and the domestic – really illustrates the socio-political landscape of the time, bridging the classical and contemporary, which adds so much intrigue to this print. It really is like an intersection where political, historical, and practical perspectives can be brought into one view. Curator: It is an instance of how printmaking democratized access to classical history, so viewers had greater control over their own perspectives of their place in society, allowing them more individual control of understanding authority and political power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.