print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

print photography

#

pictorialism

# print

#

impressionism

#

landscape

#

outdoor photograph

#

photography

#

folk-art

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

monochrome photography

#

monochrome

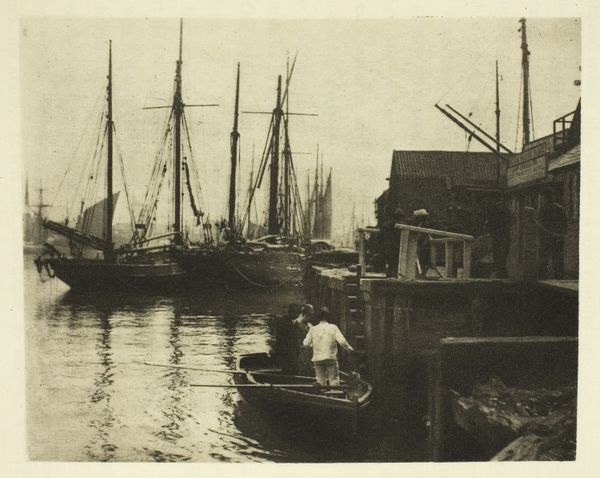

Dimensions: 14 × 26.4 cm (image/paper); 33.7 × 42.6 cm (album page)

Copyright: Public Domain

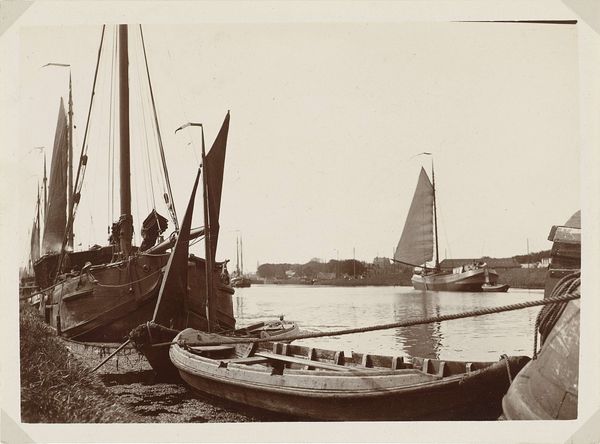

Curator: This is "Blackshore, River Blythe (Suffolk)", a gelatin-silver print by Peter Henry Emerson, dating from around 1883 to 1888. It resides here at the Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: It’s a striking image, instantly calming. The tonal range in this gelatin print creates a serene, almost ethereal mood. The softness pulls me in. It feels more like a memory than a record. Curator: Emerson was a key figure in pictorialism, advocating photography as an art form that could rival painting. His work challenged the prevailing view that photography was merely a tool for scientific documentation. How do you think the context of its creation influences how we view this work? Editor: Knowing its made by silver gelatin—you really see that depth. And think about that production; its intent! Emerson wants to demonstrate artistic skill. See how he layers elements? Dock and boats. Then you notice the large mass of sheep working with a herder. A vernacular vision of localized economy in black and white. The subject is rendered through that intent. Curator: Exactly. He often photographed rural life in East Anglia, aiming to capture what he considered authentic Englishness before it disappeared due to industrialization and the growth of cities. Some viewed his subjects, like those sheep farmers here, through an idealized lens. Editor: Perhaps. Yet even this idealization involved the labor of making prints. The gelatin silver process would have been quite involved, suggesting a real investment in transforming these humble materials and scenes into high art. Curator: And consider how photography was perceived at the time. It wasn't readily accepted into the fine art world, thus these photographic societies were built to push it forward. Editor: Yes, there’s a deliberate act of aesthetic elevation happening, which involves choosing specific landscapes and workers that resonate, given the current market. And he does an amazing job of it. Curator: Absolutely, it's a carefully constructed vision of rural England, one that speaks volumes about social and cultural anxieties of that era. Editor: Right. That tension is materially captured within the photographic surface, balancing fact and crafted visions. That labor and skill is worth contemplating.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.