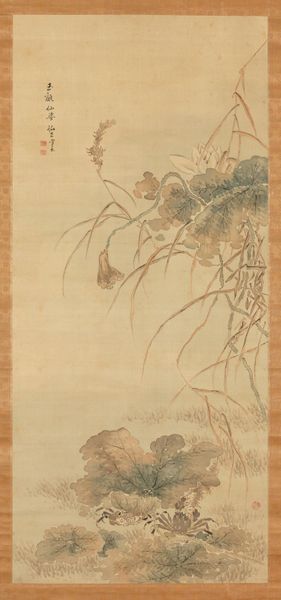

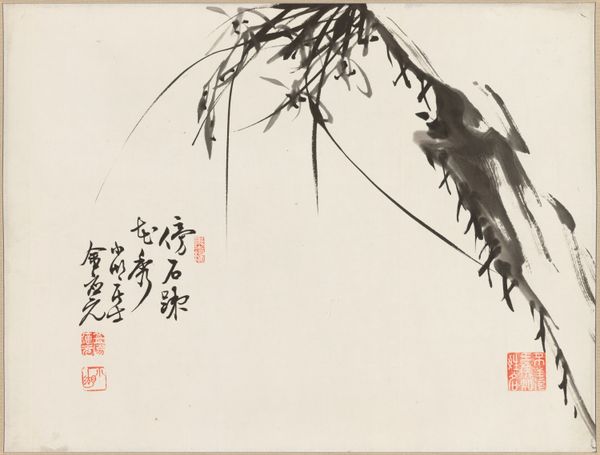

drawing, ink-on-paper, hanging-scroll, ink

#

drawing

#

asian-art

#

form

#

ink-on-paper

#

hanging-scroll

#

ink

#

line

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: Here we have Gao Fenghan’s "Ink Lotus after Bada Shanren," created around 1727. It’s an ink on paper hanging scroll, and immediately strikes me as a very deliberate study in form, with so much blank space around the lotus plants. How do you interpret this work? Curator: It is a fascinating work when we consider the materiality and process of its creation. Think about the paper itself – where did it come from? Who made it? How did the availability and quality of paper influence artistic production during the Qing Dynasty? Editor: That’s interesting; I hadn't really thought about the paper itself. So, it’s not just about the artist's skill, but also about the entire system of production that allows the art to exist? Curator: Precisely! And consider the ink: How was it manufactured? Was it locally sourced, or imported? The very act of grinding ink transforms raw materials, engaging the artist in a process connected to wider economic and social networks. Even the brushstrokes – rapid and expressive, but made possible by tools crafted through specialized labor. How does that affect the feel of the artwork? Editor: That shifts my perception a lot! The empty spaces now feel less like deliberate artistic choices, and more like inherent features in art limited by material realities and social contexts. I guess even the imitation is a reference to other works of art in the marketplace... Curator: Exactly! We’re considering production. We must ask how traditional methods continue to inform, or even limit, artists’ creative choices today. Editor: This makes me want to study more deeply into how the economic conditions impact what an artist produces! Curator: Agreed! Thinking through production allows a richer appreciation of Gao Fenghan's creation, acknowledging art not as isolated genius, but also art tied to larger realities.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Born in Shandong province, Gao Fenghan passed a special government exam in 1728 and was appointed to office in Anhui province, where he met many scholars, officials, and artists, including several from Suzhou, Nanjing, and Yangzhou. The model for this painting is the great individualist painter, Zhu Da, or Bada Shanren (1626-1705), who had a tremendous impact on Yangzhou area painters and influenced Chinese artists well into the 20th century. Wet ink has been applied in spontaneous washes that effectively capture the lushness of the lotus leaves and a wet, humid atmosphere. The formal and abstract interests of the artist, as well as his personality, are expressed in a visual performance that emphasizes the immediate emotions of the painter in spontaneously rendered images. Gao became a good friend of the eccentric Yangzhou artist Zheng Xie

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.