# print

Dimensions: height 89 mm, width 53 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

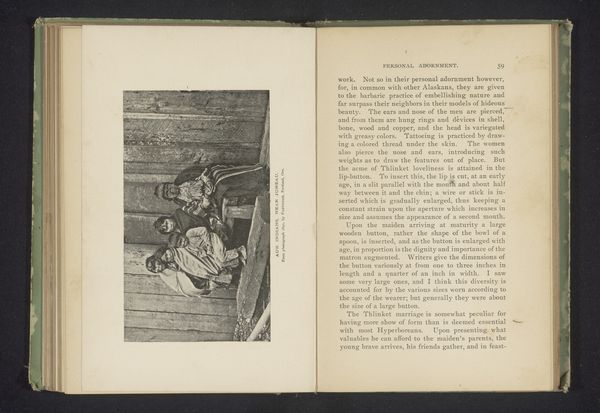

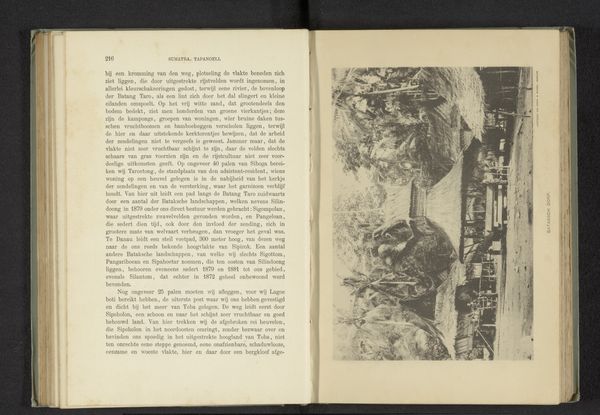

Curator: Looking at this print, “Tlingit-graven bij Fort Wrangell: de wolf en de walvis” or "Tlingit Graves at Fort Wrangell: the Wolf and Whale," dating to before 1890, what's your first take? Editor: My immediate impression is its striking visual texture and the contrast. You've got these deeply carved, weathered wooden totems sharply rendered against the backdrop of what appears to be a more recent colonial structure. The photo really captures the interplay of different worlds. Curator: Indeed. William Henry Partridge, the photographer, captures a significant moment of cultural collision. We see indigenous artistic expression—the wolf and whale carvings— juxtaposed with colonial presence embodied in the buildings. Editor: The means of production is particularly fascinating here. Carving such totems would have required immense skill, labor, and access to specific natural resources like cedar wood. These were not casual crafts. How does Partridge represent the materiality? Curator: Partridge gives us insight into the complexities of identity and resistance within the Tlingit community. The totems can be interpreted as powerful symbols of Tlingit heritage. Despite the colonial backdrop, the community asserts its presence and cultural narrative. We can explore the ways in which gender roles or societal hierarchies may be manifested. The wolf, the whale – these choices weren't accidental, they communicated very specific messages. Editor: It begs the question of labor relations, doesn't it? Who commissioned Partridge for this work, and what was the photograph meant to signify to its contemporary viewers? This piece gives insights into the indigenous craftsmanship in Alaska, the ways in which the art objects are tied to ritual and community life, as well as potential commodification within emerging markets. Curator: Precisely. It’s essential to investigate beyond the visual to uncover historical implications and connect with broader discussions on cultural heritage and decolonization in the region. These photographs acted as tools. They are pieces of social commentary and reflections of lived experiences of the sitters. Editor: So, what begins as a seemingly straightforward photograph unravels into layers of social, economic, and cultural exchanges. That is where its true value lies for me. Curator: Absolutely. By examining the subject from multiple perspectives we gain a richer, more nuanced view of the complex relations. Editor: It underscores the responsibility we bear to approach works from the past through careful and critical lenses.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.