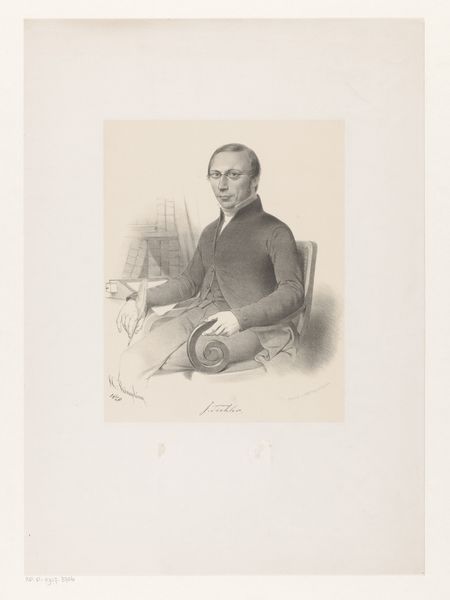

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

pencil work

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 365 mm, width 275 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

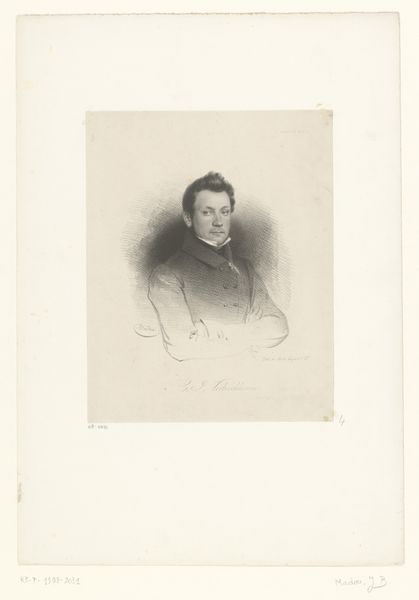

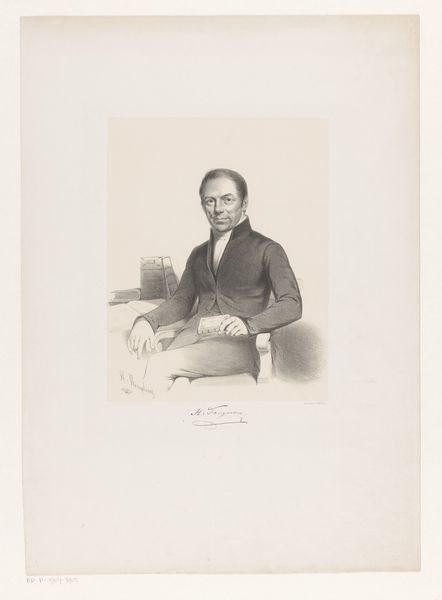

Curator: Standing before us is "Portret van Jacobus Leunis van der Vliet" crafted between 1842 and 1851 by Carel Christiaan Antony Last. It’s a pencil drawing, currently residing here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first thought is the incredible stillness and contained energy—almost a Victorian-era austerity rendered so softly through pencil. Curator: The medium itself is key here. Consider pencil as a relatively accessible material, widely used in academic studies. Its ability to render subtle tonal variations enabled artists like Last to achieve incredible realism without the need for expensive paints or a large studio setup. This also hints at its circulation in different levels of Dutch society, from student workshops to elite patrons. Editor: Precisely. And looking at Jacobus Leunis van der Vliet himself, we can speculate about his position and aspirations. The sharp tailored jacket, eyeglasses… He seems to embody the emerging professional class. The artist makes it clear through sharp sartorial choices. His attire could even indicate belonging to some sort of intellectual or social organization; these clues contribute to the larger picture of his era. Curator: Indeed, this wasn't just about portraying likeness but projecting a certain image aligned with specific social roles. The details we can grasp through materiality are really stunning! Looking at the surface of the paper, we can surmise much of how popular paper as a material has evolved in that time. What do you suppose this tells us about a society with an exploding need to classify the image in an accurate fashion? Editor: Absolutely. His reserved expression reads like a conscious performance—a deliberate construction of identity meant to be conveyed and interpreted within certain social and political confines. It calls us to critically examine constructions of masculinity. Curator: So, as a relatively affordable means of visual documentation, pencil allowed the rising Dutch middle-class to participate in, and consume portraits and art in new ways. In this regard, accessibility, in a raw materialistic approach, drives consumption, self-representation, and consequently representation of gender and political standing! Editor: Thinking about his place now, here in the museum, it compels us to constantly question the power dynamics inherent in display, preservation, and ultimately, how his representation here at the RijksMuseum either amplifies or obscures his identity. Curator: Absolutely. Materiality is key! I have learned that understanding what drives human society and art-making is also tied to material realities of a specific period! Editor: I have realized that it requires looking at the man himself and questioning what is truly captured or projected onto paper by both sitter and the artist!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.