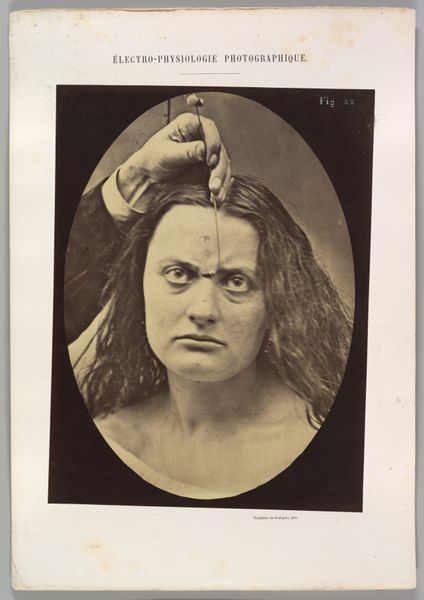

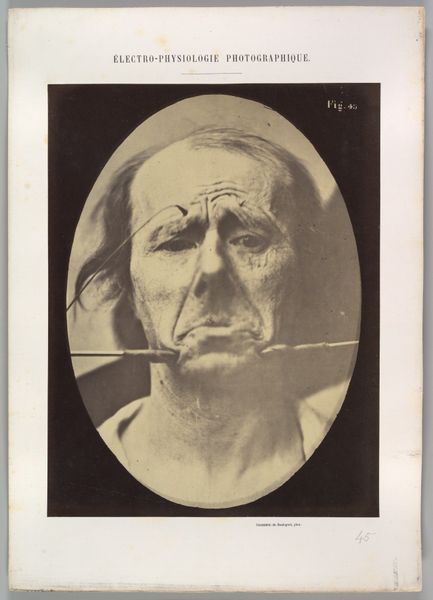

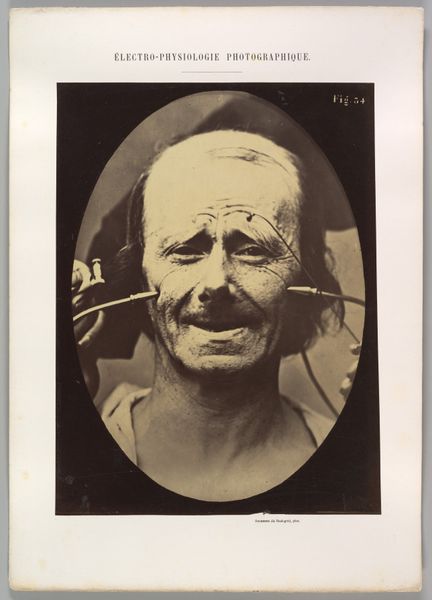

Figure 83: Lady Macbeth, ferocious cruelty 1854 - 1856

0:00

0:00

Dimensions: Image: 28.3 × 21.4 cm (11 1/8 × 8 7/16 in.) Sheet: 30 × 22.9 cm (11 13/16 × 9 in.) Mount: 40.2 × 28.4 cm (15 13/16 × 11 3/16 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

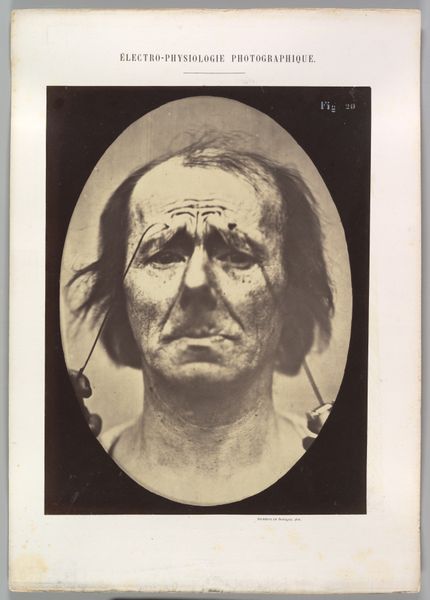

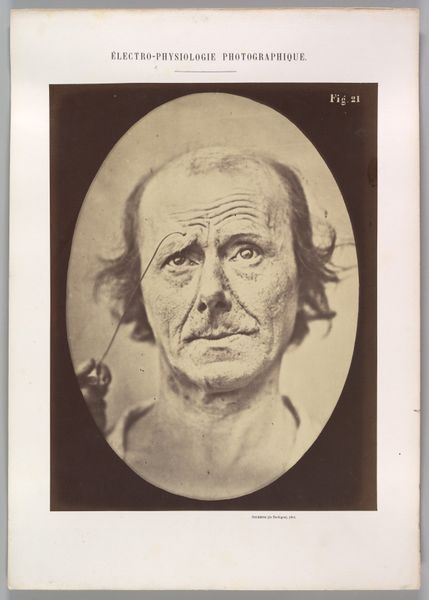

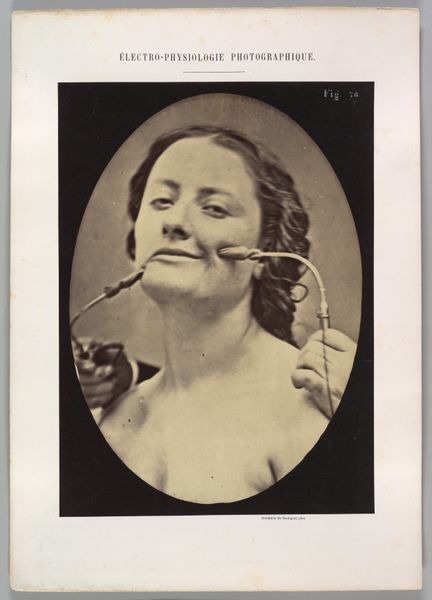

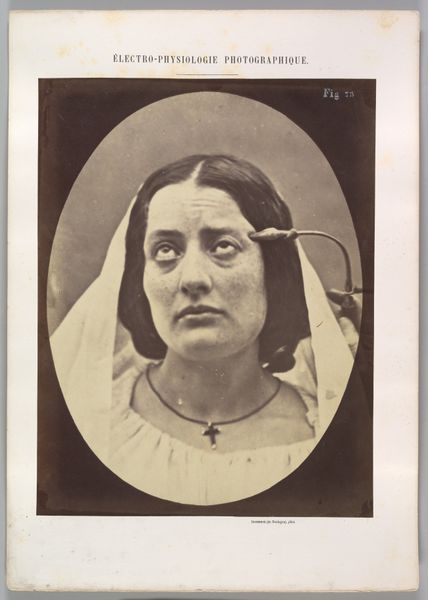

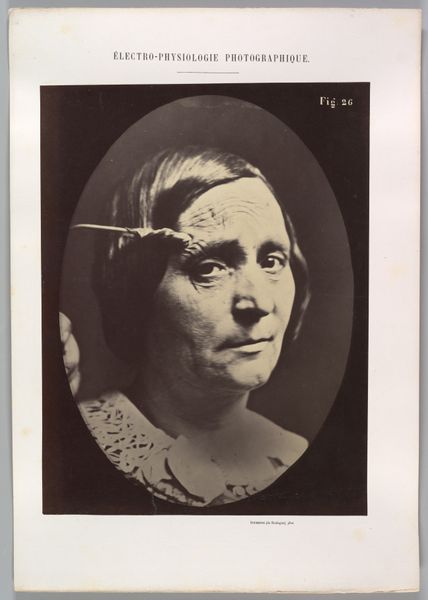

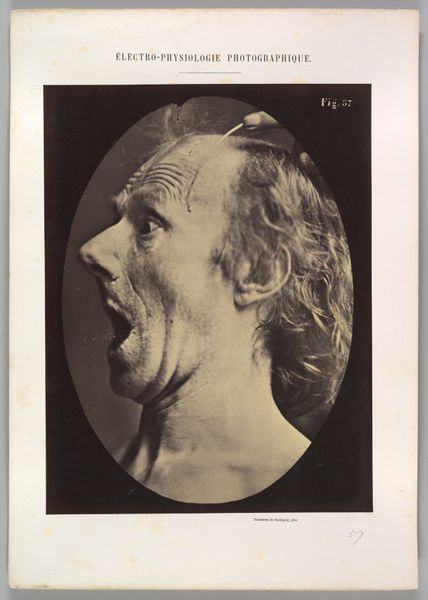

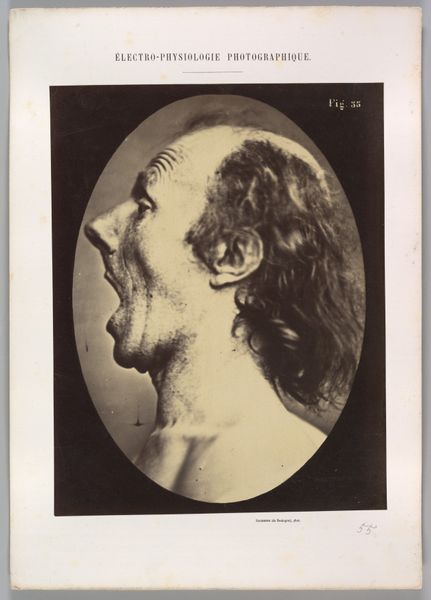

Curator: Let's turn our attention to "Figure 83: Lady Macbeth, ferocious cruelty," a photograph dating from 1854 to 1856 by Guillaume Benjamin Amand Duchenne. It resides here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: That's certainly…intense. There's something deeply unsettling about the expression. It's so raw, almost theatrical in its extremity. The dramatic shadows emphasize the exaggerated lines around the eyes and mouth, amplifying what you described as “ferocious cruelty”. Curator: Precisely. Duchenne was interested in isolating and mapping the muscular mechanics of facial expression. In this portrait, you see his effort to depict a very specific emotion, cruelty, by electrically stimulating the muscles of his subject. The aim was to provide a scientific basis for understanding emotion. Editor: The social context is incredibly disturbing when you consider that Duchenne's experiments relied upon patients at a mental institution. There’s an ethical dilemma that persists: the vulnerability of the subjects, often women, compounded with medical objectification under the guise of scientific progress. It brings into question the institutional forces that were at play here. Curator: That is certainly something that contemporary audiences consider in regards to the socio-political climate of the time. This image resonates with Romanticism through its interest in strong emotion, but as photography, it sought objectivity. It’s quite the dichotomy. The attempt to scientifically dissect and categorize inner emotional states presents a view of how art and science sought to interpret humanity. Editor: What do you think that Shakespeare and his creation of Lady Macbeth had to do with Duchenne choosing to use a reference with this historical figure for the work? Curator: Duchenne leveraged pre-existing cultural understanding by borrowing historical, fictional, or allegorical figures in the Western consciousness, thereby making them readable for the scientific, artistic, and cultural discourse of the time. Editor: Understanding that this work emerges from that era's complex interaction of art, science, and societal norms makes us reflect critically on how institutions shape what we perceive and come to accept. Curator: Yes, absolutely. Viewing the artwork as a window into that complicated dynamic—the scientific, artistic, and societal context from which it arose, offers insight that shapes what we come to learn and accept, and in our case, to question.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.