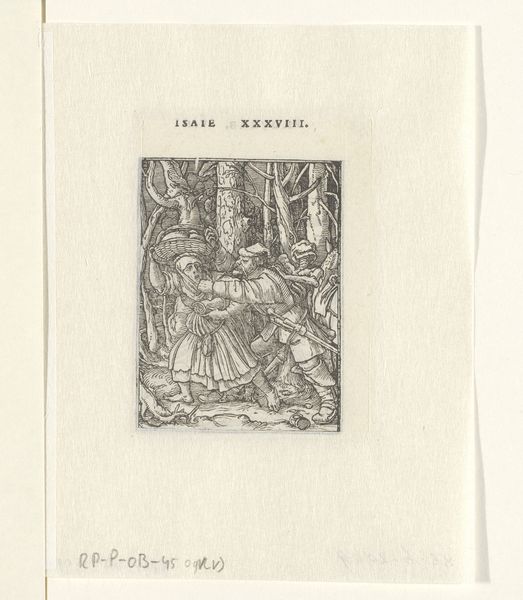

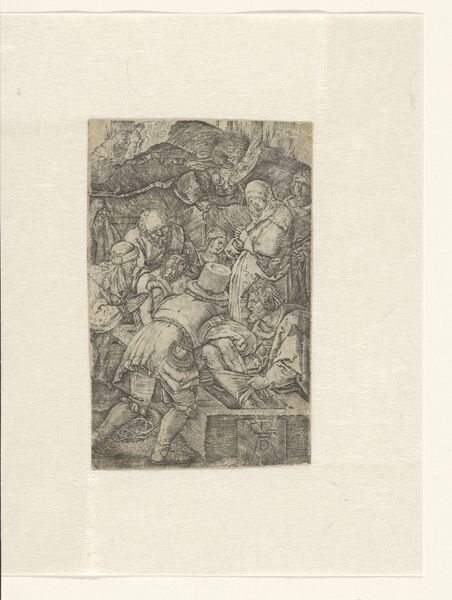

print, woodcut, engraving

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

woodcut

#

line

#

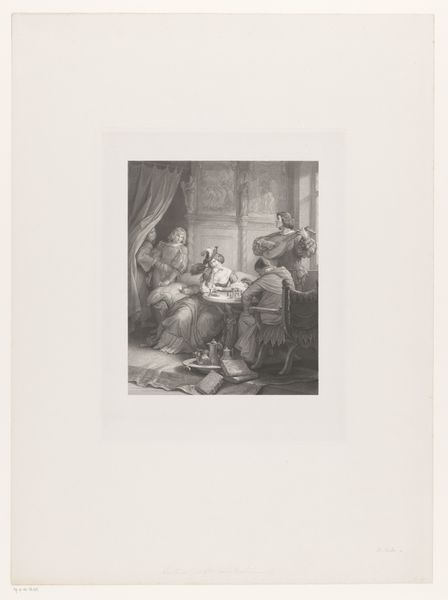

genre-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 65 mm, width 50 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

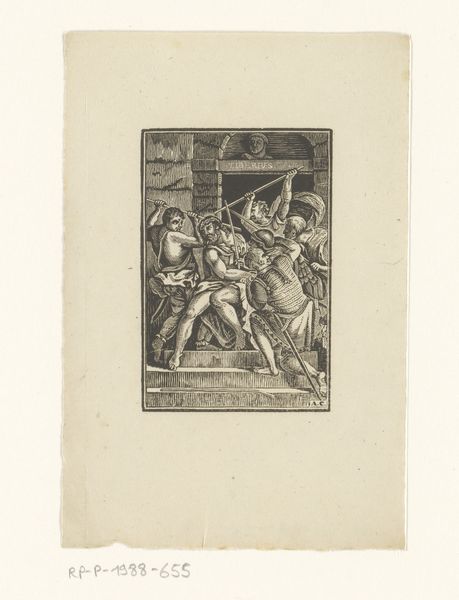

Curator: This engraving by Hans Holbein the Younger, titled "Dronken man en de Dood," which translates to "Drunk Man and Death," dates back to 1547. It’s a rather small print, currently held in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My immediate impression is a stark, almost grim atmosphere. The linework is incredibly precise, creating a scene overflowing with bodies, food and drink, and a palpable sense of unease despite the seemingly celebratory setting. Curator: Absolutely. Holbein, working within the Northern Renaissance tradition, frequently engaged with themes of mortality and social critique. This work serves as a visual commentary on the pervasive presence of death amidst life's fleeting pleasures. He questions the period’s socio-economic reality, class differences, and, most critically, how death equalizes all irrespective of social rank. Editor: You're right. Seeing Death standing among them, but seemingly unacknowledged by most, introduces a critical lens. The drunken man is clearly the focus, oblivious and overwhelmed by sensory indulgence, unaware of the grim reaper hovering nearby. It highlights a kind of willful ignorance, perhaps representative of society’s broader denial of mortality. Are we reading this piece as a political act or one addressing society’s blindspots? Curator: I would say both elements coalesce. During this period, visual art was strategically deployed to disseminate sociopolitical commentary and morality. Considering that this image likely circulated widely through prints, it could catalyze discussions about the intersections between mortality, indulgence, and broader societal well-being among a varied audience. The stark figures underscore the urgent social and religious issues of the time, a powerful call for self-reflection. Editor: Indeed, reflecting on what societal consumption and privilege costs is perpetually critical. Curator: Looking closer, what this piece tells us about life during the 16th century remains striking. Editor: A very timely observation as always!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.