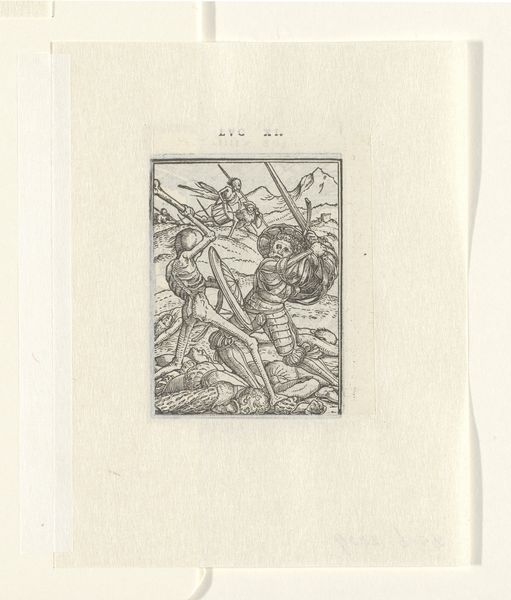

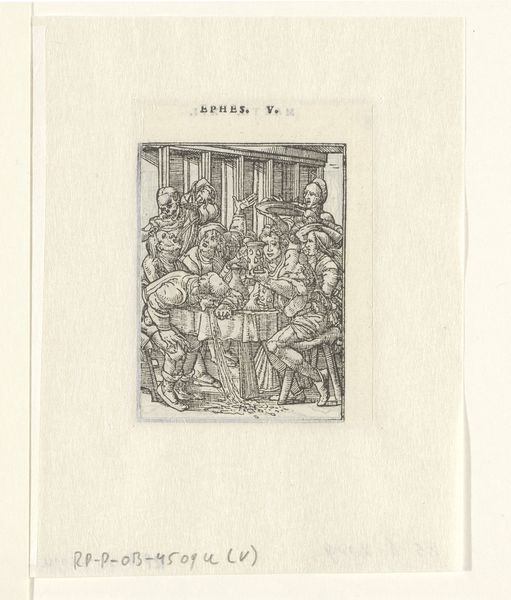

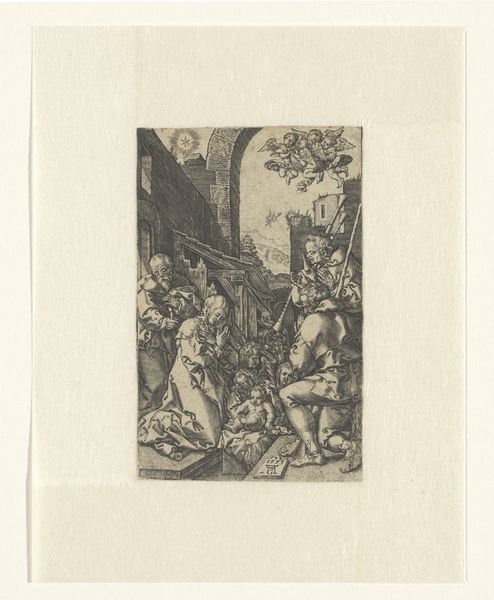

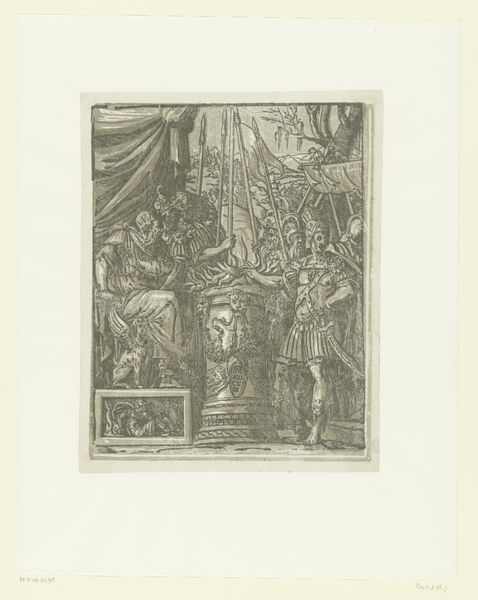

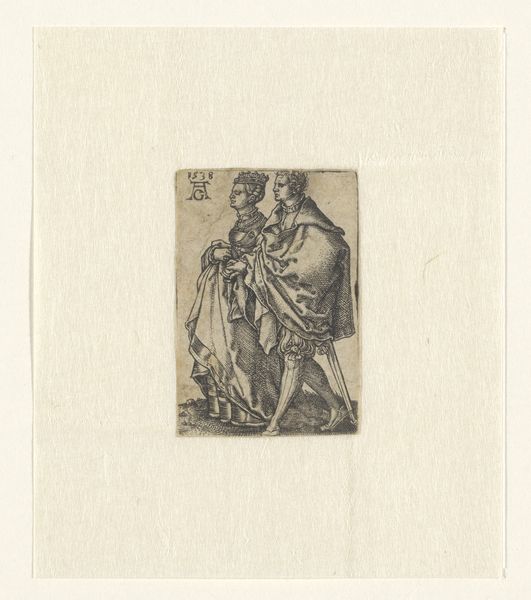

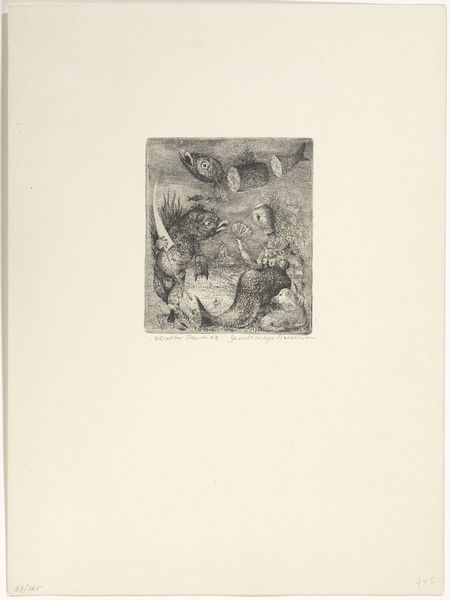

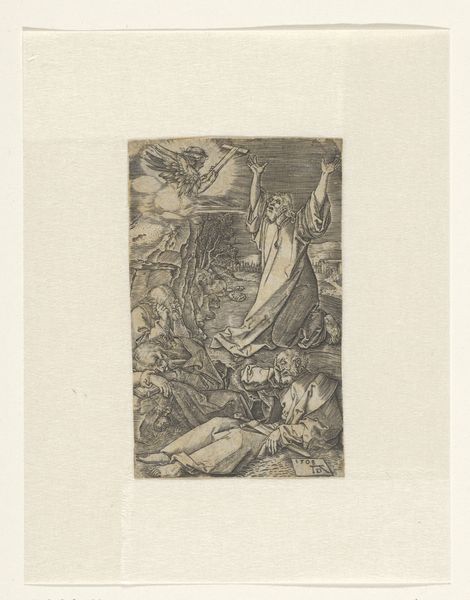

print, woodcut, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

woodcut

#

line

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 65 mm, width 50 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Hans Holbein the Younger’s "Dief en de Dood," created in 1547. It’s a woodcut, with incredibly fine lines. I’m struck by how it captures a moment of such violent confrontation in what seems like a remote, almost fairytale setting. How do you interpret this work within its historical context? Curator: This image, part of Holbein's *Dance of Death* series, speaks volumes about the social anxieties of the 16th century. Death is depicted not as a solemn reaper, but as an active participant in life, disrupting the social order by attacking a thief. This points to the period's preoccupation with morality and social hierarchies threatened by forces like disease and economic instability. The Church’s stance on moral punishment heavily influences depictions of life and death. Does the thief’s placement, set in a dense forest rather than a town, change your interpretation? Editor: That’s fascinating. It does make me wonder if the forest represents a space outside the usual societal rules, a lawless zone where even Death acts differently. So the woodcut reflects a world where the established order is constantly being challenged? Curator: Precisely! Consider the role of prints themselves during this period. They were relatively inexpensive and accessible, enabling the widespread dissemination of moral and political commentary. *Dance of Death* wouldn't have been confined to the elite; it reached a broad audience, sparking discussions and reinforcing societal norms or, conversely, inciting questions. How might the location of this image within the Rijksmuseum change our interpretation of the imagery and intention behind Holbein's creation? Editor: Hmm, placing it in a museum setting almost domesticates it, removing it from that direct socio-political battleground. It transforms from propaganda into a piece of art for contemplation. Curator: Exactly. And in doing so, the museum gives its imprimatur to a particular understanding, further shifting its significance through curation, exhibition design and this audio guide. It underlines how context radically changes an object’s meaning. Editor: I’ll definitely keep that in mind when studying art. Thanks for your insight!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.