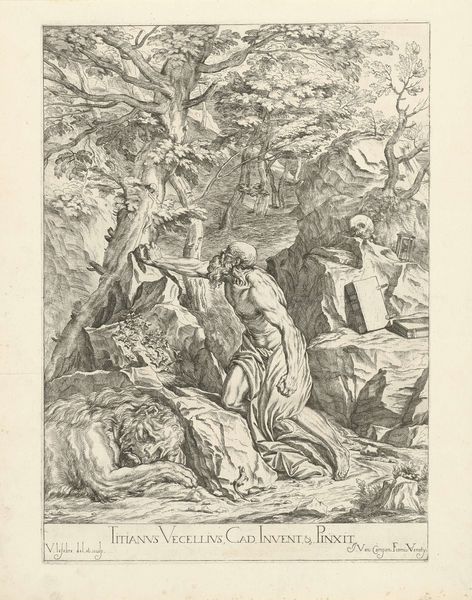

drawing, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

baroque

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

history-painting

#

sketchbook art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 193 mm, width 146 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is "The Sacrifice of Isaac," a pen and ink drawing by Arnold Houbraken, created sometime between 1681 and 1699. It depicts Abraham about to sacrifice his son. The landscape is beautiful, but the overall tone feels unsettling, almost like a nightmare. What do you see in this piece, beyond the literal representation of the biblical scene? Curator: I see a potent commentary on power, faith, and the vulnerability of marginalized groups. Consider the social structures of the 17th century. Divine right was still very much a leading ideology. How does this image interrogate patriarchal authority and the demands placed upon those who are subjugated to it? Editor: You're right, it’s a very patriarchal scene. The power dynamic is obvious, but I hadn’t thought of it in the broader context of societal power structures at the time. Do you think Houbraken was critiquing religious dogma? Curator: Perhaps not overtly, but the visual tension is palpable. The etching forces us to confront the ethics of blind obedience. Look at the expressions, or lack thereof, on Abraham and Isaac’s faces. Think of it from a feminist perspective - how many times in history has a similar narrative, demanding subjugation and self-sacrifice from women and other oppressed groups, been perpetuated in the name of religious or societal expectations? Editor: It's a difficult but necessary viewpoint to take. Examining power dynamics, especially in historical artworks, helps contextualize the artwork, especially since "religious freedom" often carried complex caveats regarding who was truly "free". Curator: Precisely. Analyzing artworks through intersectional lenses—race, class, gender, religious affiliation—allows us to challenge conventional art historical narratives and engage in more equitable, meaningful discussions about art's role in society. Editor: This has completely shifted how I view the drawing. It's no longer just a depiction of a biblical story but a mirror reflecting the enduring struggles against oppressive power structures. Curator: And hopefully, this awareness will fuel future investigations that are crucial to any engagement with this piece, so, this allows us to understand that history has repercussions in the present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.