Copyright: Public domain

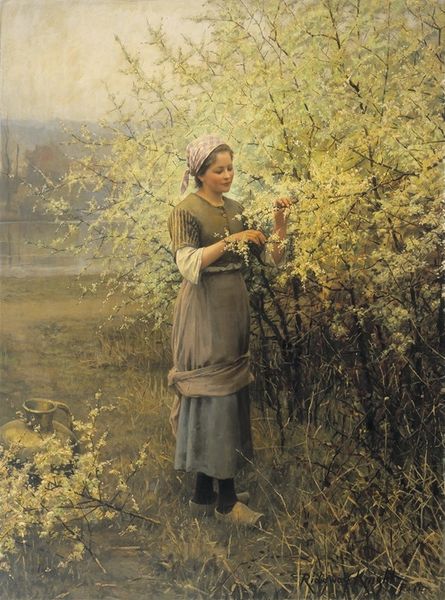

Curator: Standing before us, we have "Last Flowers" painted by Jules Breton in 1890. He's really capturing a specific feeling, I think. Editor: Yes, there is a certain melancholy isn’t there? The pale light, the snow, it all creates this quiet sense of closure as the young woman delicately cuts some final blossoms. It almost reads as a winter allegorical scene about human toil. Curator: It certainly places this very individual woman within a specific social narrative. During the late 19th century, Breton became well known for his depictions of rural life, often romanticizing peasant workers in a manner aligned with prevailing artistic trends and political sentiment. She is pretty. But who are those pretty flowers for? And in which way is the artist involved in French national ideologies? Editor: I’d say Breton shows clear control over composition; consider the light that falls across her face and how the background subtly fades. Even her pose--caught mid-action, her fingers barely touching those last blooms-- speaks to a fleeting moment, very typical of the impressionists, that elevates it above a mere genre painting. Curator: These so-called ‘fleeting moments’ were politically charged images. Academic art institutions played a role, they had the power in selecting which types of scenes, figures and colors can represent the idealized national identity. Genre scenes such as "Last Flowers" validated a sentimental connection to agricultural life, at the time when France was in the midst of political conflicts around urbanity, rural life and social change. The symbolism matters. Editor: True, but the surface quality is something to behold here, too. Notice how Breton plays with light and shadow, creating a beautiful chromatic harmony across the cold atmosphere of the snowy rose garden, that somehow warms the overall scene with its delicate touch. The material application heightens the sensory experience, it makes me cold, in a strangely pleasant way. Curator: In closing, this seemingly straightforward image reveals Breton’s role within a larger discourse of art and nationalism during the late 19th century in France, where his images became deeply woven into the national fabric. Editor: I see that. But despite that, it's this attention to form and texture and fleeting moments, more than political undertones, that allows this painting to affect us to this day.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.