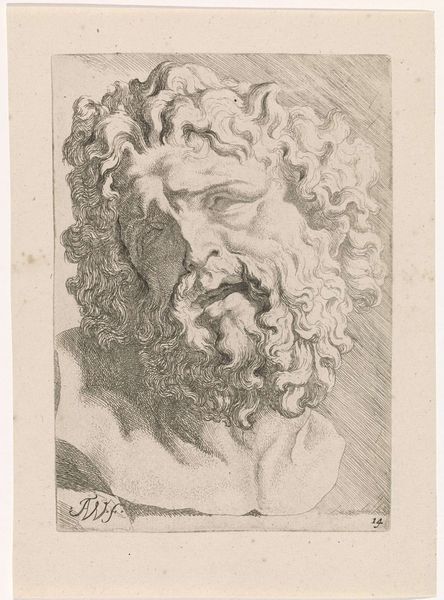

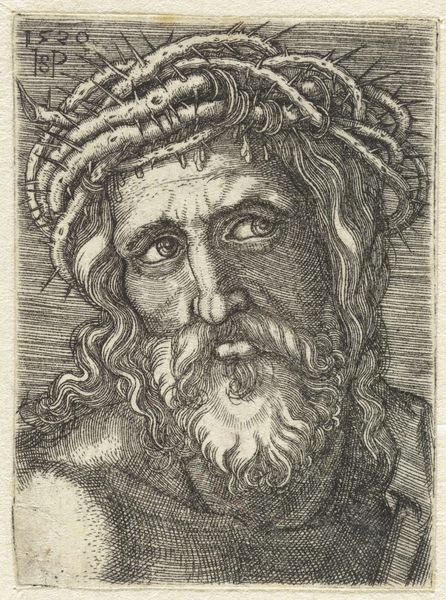

engraving

#

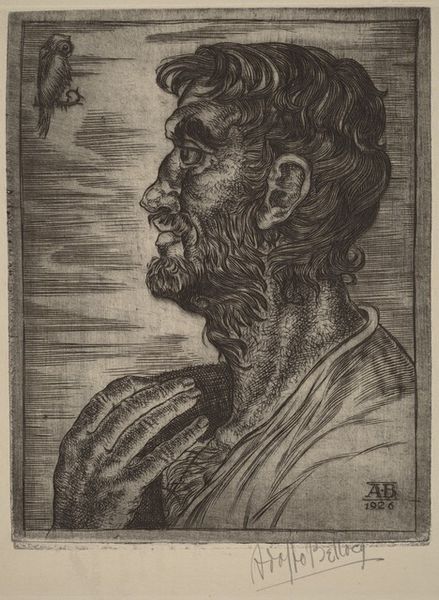

portrait

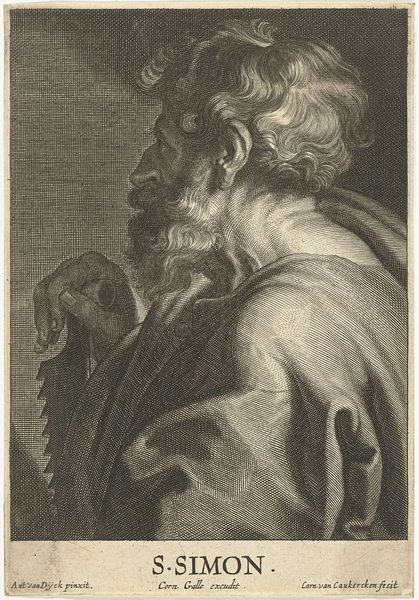

#

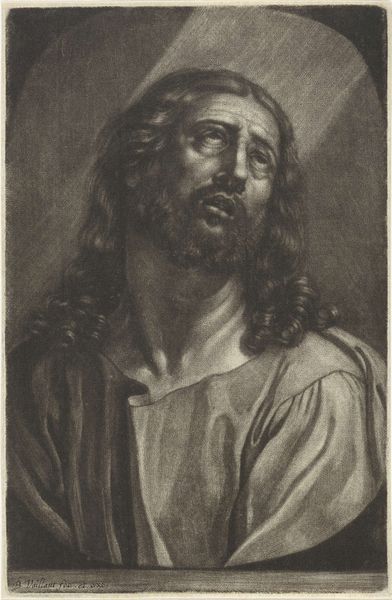

baroque

#

figuration

#

line

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 113 mm, width 93 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Pieter Lastman's "Bust of a Praying Man," created sometime between 1593 and 1633 using engraving. The linear detail is quite striking, but what's most compelling is the subject's implied emotional state. What stands out to you about this piece? Curator: I am particularly drawn to how Lastman, through the material act of engraving, democratizes representation. Traditionally, portraits of the praying were reserved for elite patronage, manifested through costly oil paints and large canvases. Here, the relative affordability and reproducibility of engraving open up the possibility of portraying religious figures and their emotional states, potentially to a wider audience. Consider the physical labor involved in creating these dense networks of lines, etched into a metal plate. How does that labor shape our understanding of the man depicted and his act of prayer? Editor: That’s fascinating! So you're saying the medium itself challenges the traditional power structures surrounding religious art? How does the context influence your reading? Curator: Absolutely. And looking at the proliferation of such engravings, what social functions do they perform? Were these prints meant for personal devotion, circulated as devotional aids? Consider also the economic implications of printmaking. Were they a source of income, offering Lastman an independent avenue for production outside traditional patronage models? This is baroque art produced in an easily consumable format. Editor: I never considered how the act of engraving could be interpreted as a social commentary itself, challenging those elitist art circles! Curator: Precisely. The focus isn't simply on aesthetic appreciation but also on interrogating the means of production, circulation, and social function. It gives "Bust of a Praying Man" so much new value when you begin to recognize how this choice of engraving adds cultural and material layers. Editor: Thanks! Thinking about its material context makes me consider who owned these and what their lives may have looked like, too.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.