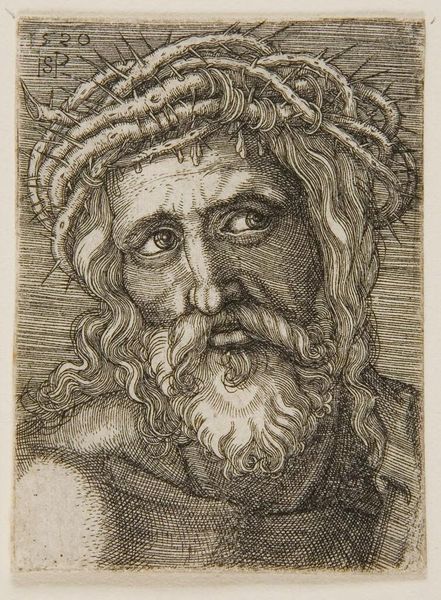

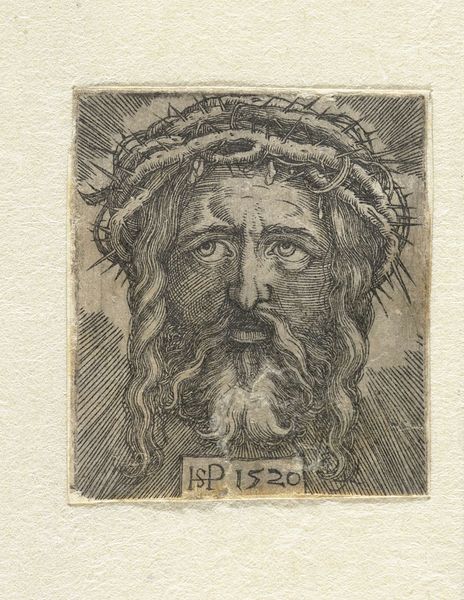

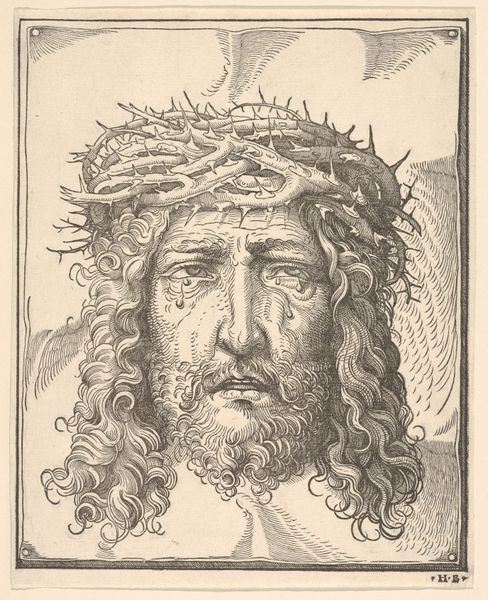

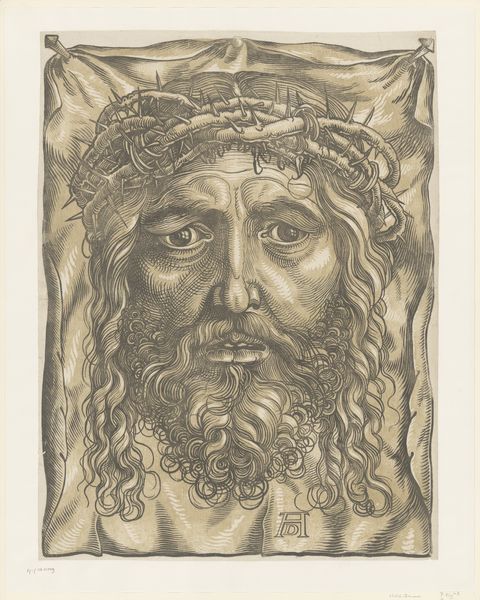

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

figuration

#

form

#

line

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 52 mm, width 38 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Sebald Beham's "Head of Christ with the Crown of Thorns," an engraving from 1520 housed in the Rijksmuseum. The overwhelming detail achieved with line work really grabs your attention. How should we think about this print? Curator: The process of creating engravings like this reveals much about the relationship between art and labor in the 16th century. Beham, part of the German Little Masters, produced small, intricate prints for a growing market. Consider the intense labor involved in cutting those lines into a copper plate. Each mark meticulously placed, creating tone and form. Editor: So, the act of production itself is key? Curator: Absolutely. How does the mass production of prints, readily consumed and traded, democratize access to religious imagery while also commodifying the suffering of Christ? Who was buying these images? What purpose did they serve in the homes of ordinary people? The material reality of this object—the paper, the ink, the engraved plate—all point to a complex web of economic and social relations. Notice, also, that while the subject is overtly religious, it also works within the popular portrait style. Editor: It’s interesting to consider the religious aspect as both a source of reverence and something that’s almost packaged for consumption. Curator: Precisely. The physicality of the print—its texture, scale, and the very act of its making—opens up avenues to discuss piety, commerce, and the changing role of art in society. I think that understanding its means of production can change our understanding. Editor: It gives a whole new layer to something I just saw as a somber image. Curator: Indeed. Paying attention to these details contextualizes both the image and its means of production, as an entry point to understanding society at the time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.