Copyright: Public Domain

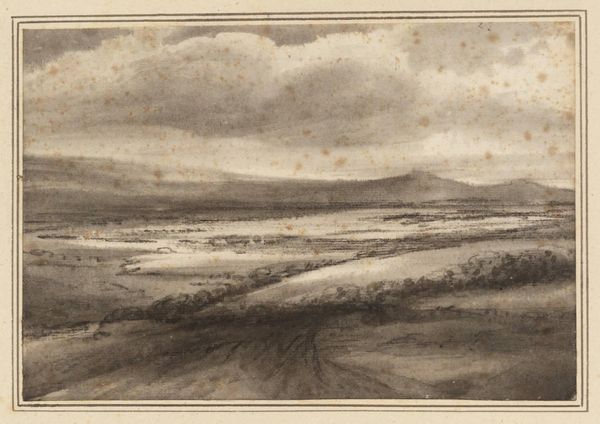

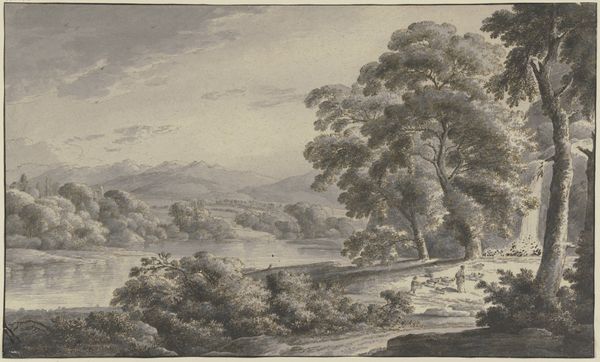

Curator: Here we have Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s "Mountain Landscape with Haystacks in Moonlight", created around 1787. It's a work rendered in ink, chalk and charcoal, currently residing at the Städel Museum. Editor: My first impression is one of serene solitude. The limited palette really focuses your eye on the textures and subtle gradations of light and shadow across the landscape. It feels very romantic, almost like a dreamscape. Curator: Absolutely. Consider the romantic fascination with nature and the sublime, common amongst artists of the late 18th century. Goethe wasn’t just a writer, but an avid student of natural science; his sketches served almost as fieldwork observations of the natural world, documented through art-making practices. Editor: So, not just an artistic endeavor, but a form of material investigation as well? It strikes me that the haystacks, these carefully constructed agricultural objects, take center stage in contrast with the distant, seemingly untouched mountain. Is he commenting on the imposition of human labor on the landscape? Curator: That’s an interesting observation. Think about the social context of the time. These agricultural scenes weren’t mere idyllic depictions of rural life; they reflect the very real labor systems in place. Also, the act of turning a natural resource—hay—into a carefully constructed form is what strikes me. How those materials are being transformed speaks of larger production economies that dictate this way of life and transform that material. Editor: It makes you wonder about the viewers, doesn’t it? This drawing likely wouldn't have been seen by the working class actually constructing the haystacks, but by a privileged, educated elite within a very exclusive circle. How does its status change through display within a museum, removed from its initial context? Curator: Precisely. It raises important questions about the circulation and reception of art and its role in shaping societal values across historical divides. Its presence here forces us to confront those contextual layers. Editor: Well, reflecting on the moonlit scene and considering all the layers, from material transformation to reception history, it provides such a richer and deeper appreciation. Curator: Indeed, seeing this as a document of production and historical artifact, rather than simply an aesthetic representation, completely shifts how we understand and value its historical importance and social legacy.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.