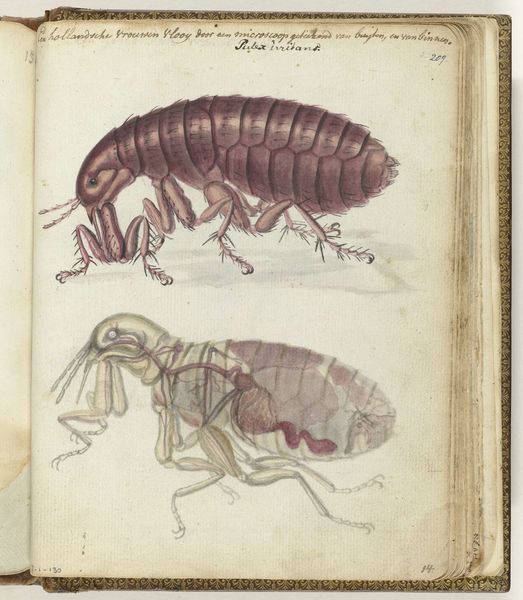

drawing, coloured-pencil, plein-air, paper, watercolor, ink

#

drawing

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

coloured-pencil

#

plein-air

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

watercolor

#

ink

#

coloured pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

watercolour bleed

#

watercolour illustration

#

naturalism

#

sketchbook art

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 195 mm, width 155 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

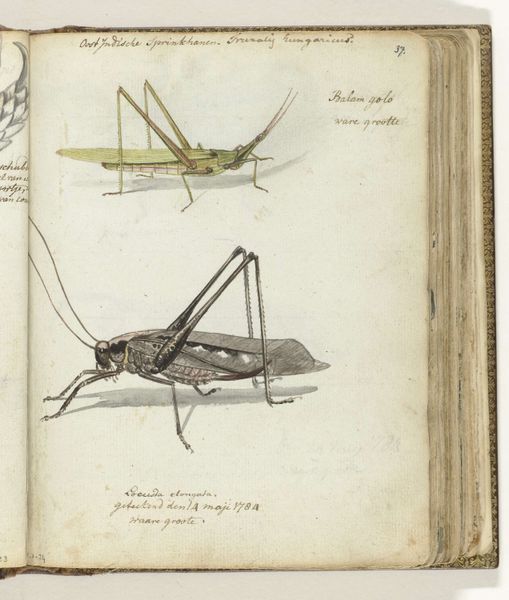

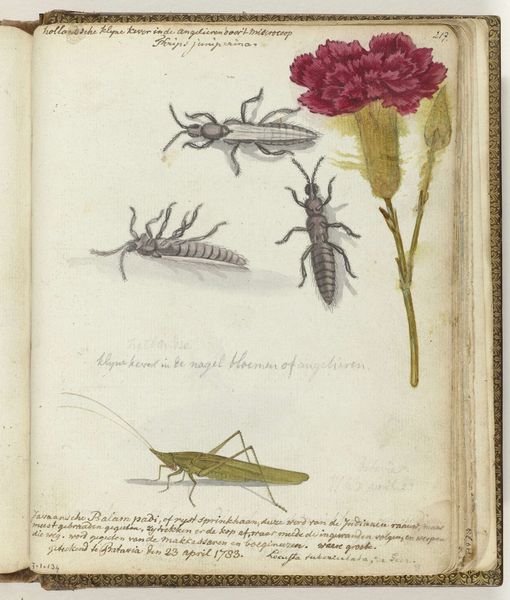

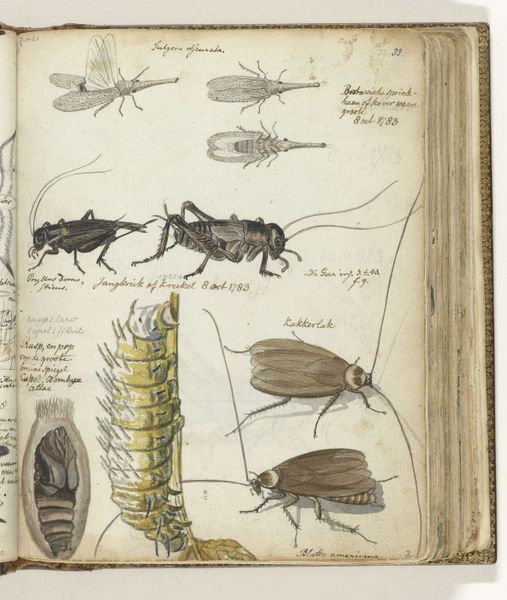

Curator: Here we have "Javaanse bijen en sprinkhaan," or "Javanese bees and grasshopper," possibly created between 1783 and 1787 by Jan Brandes, rendered in watercolor, ink, and colored pencil on paper. The delicate lines and faded pigments give it a sense of aged elegance. How do you see this work? Editor: The drawing feels like a page torn straight from a naturalist's field journal. I’m struck by the way the artist meticulously depicted these insects, but I'm wondering about the social or cultural context in which Brandes made it. Why preserve such detailed depictions of insects? Curator: A vital question. Consider Brandes's presence in Java during that period. The work is less about pristine "high art" and more about the labor of observation, documentation, and knowledge production within a colonial context. These weren't just pretty pictures; they were specimens, data points within a larger system of resource extraction and scientific categorization. How does recognizing that shift your perspective? Editor: That reframes the image. It's no longer simply a charming natural study; it's a record embedded in the history of colonial science. The labor is embedded into the artistry, transforming how these materials operate. What did Brandes intend to do with this cataloguing? Curator: Exactly! And what impact do you think it would've had back home, where they consume the product of that system? What kind of knowledge did such imagery produce, and whose interests did it serve? Thinking about these sketches in that light makes you rethink the boundary between art and labor and material consumption. Editor: I see it now! Thanks to your perspective, I see how Brandes’s sketches aren't separate from economic activity, colonial politics, and how he used common media like pen and ink, plus personal notebooks to catalogue resources for a far away public. It ties the seemingly innocent with its connection to exploitative and historical conditions of possibility. Curator: Precisely! Recognizing these connections reveals the complex story embedded within seemingly simple artworks and our own participation as its audience and beneficiary.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.