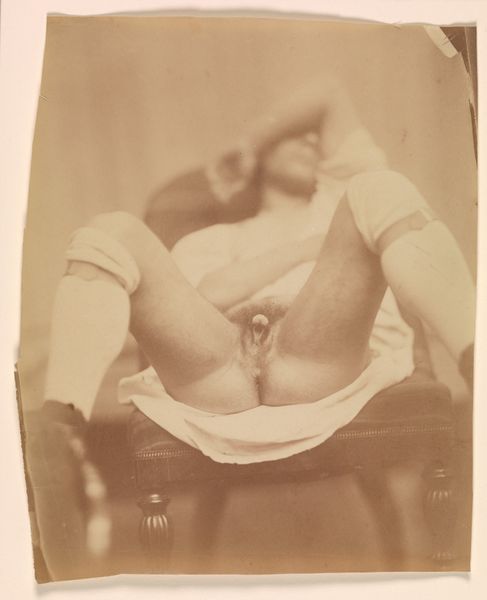

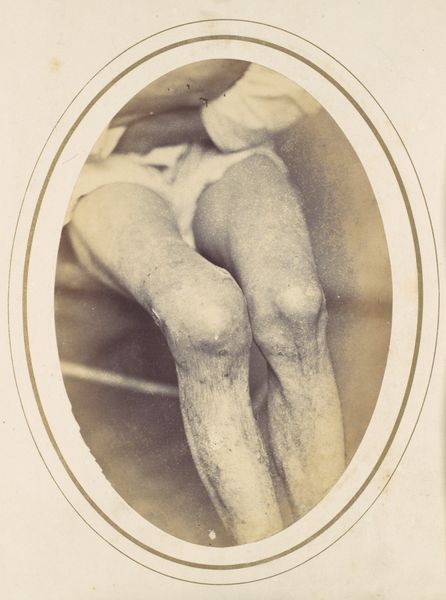

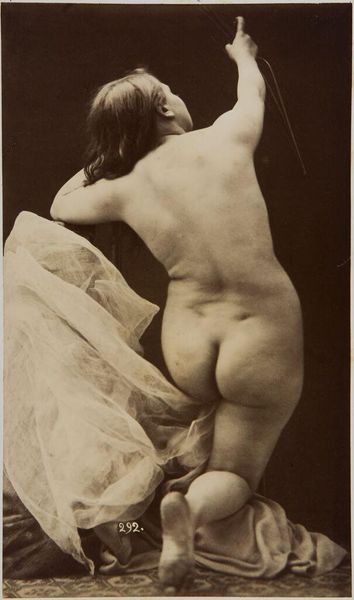

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

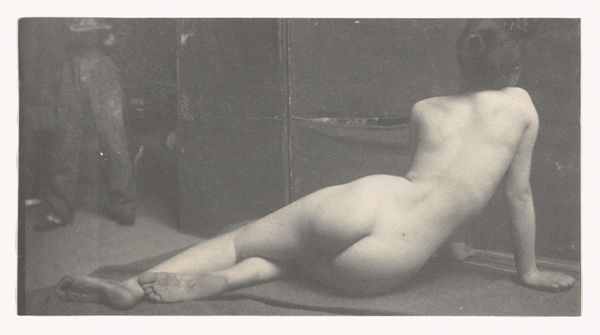

photography

#

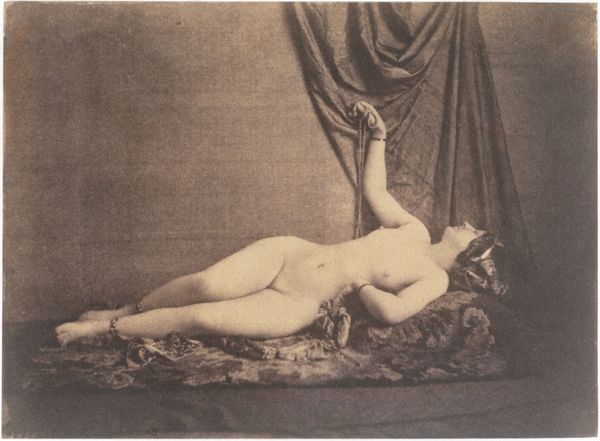

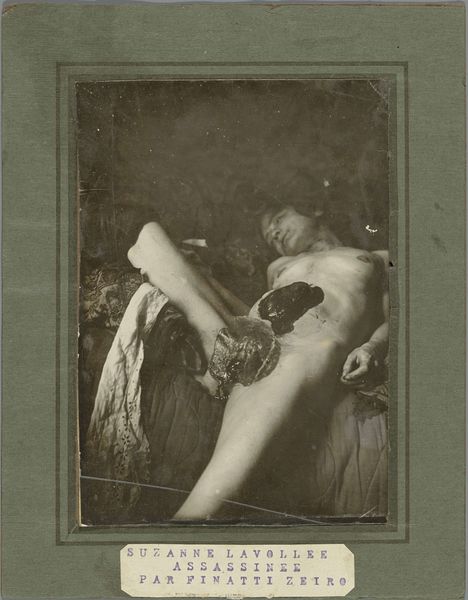

history-painting

#

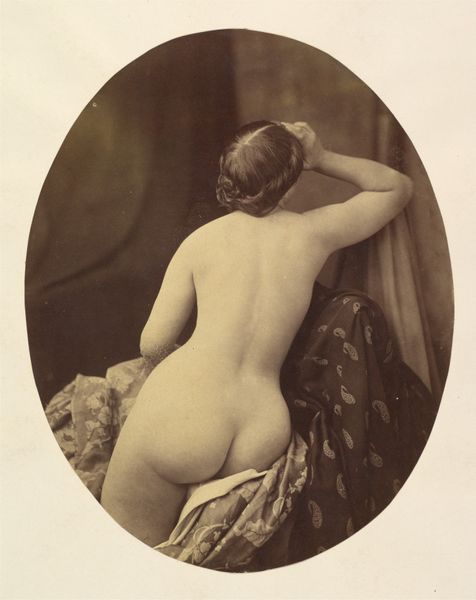

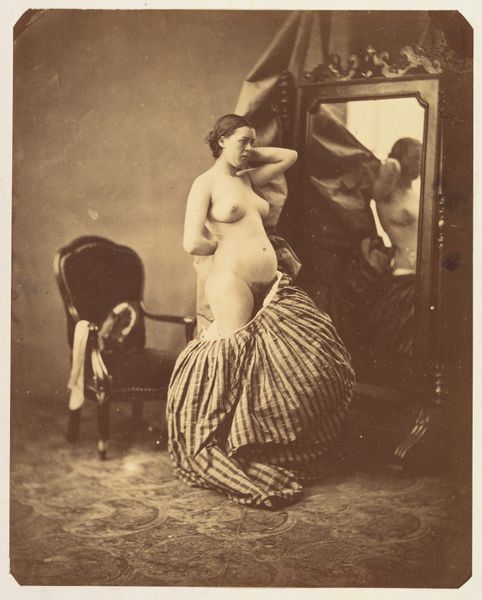

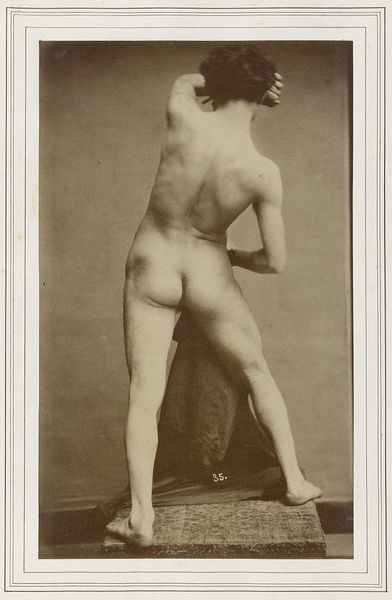

academic-art

#

nude

#

erotic-art

Copyright: Public domain

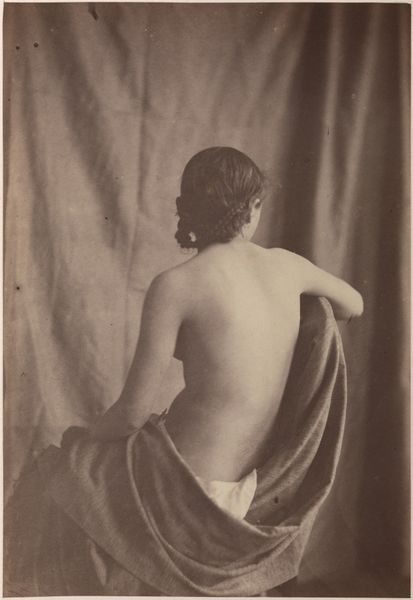

Curator: This image is a photograph titled "Hermaphrodite," taken around 1860 by Félix Nadar. It's a daguerreotype, which was a very early photographic process. Editor: Oh, wow. Okay. My immediate feeling is...vulnerability. It's so stark, so... raw. The limited tonal range makes it feel almost like a faded memory, and it evokes... discomfort, to be honest. Curator: Discomfort is a fair reaction, considering the complex issues of gender, representation, and power dynamics involved. It is impossible to look at it today without thinking of the colonial and patriarchal structures that produced images like these and how they fit within art historical frameworks. We have to look at how gender non-conforming bodies have been exoticized throughout history. Editor: Yes. It's this tension, isn't it? This sense of a hidden narrative trying to break free. It looks posed; like the person was an actor for somebody else’s script. And who gets to decide what a "hermaphrodite" is? How they’re seen? You just feel them staring out from the photo asking, “And what do YOU think you're looking at?” Curator: Precisely! The photographic process itself needs examination. It was an emerging technology at this point, lending an aura of scientific objectivity. But even the "objective" eye is socially conditioned. In viewing this image through today’s lens, one can’t escape questioning the power structures implicit in creating it and its problematic place within visual culture. This brings the crucial importance of approaching the artwork in its socio-political time, and also from today’s theories that allow a space of revisionism. Editor: Right, it’s all layers of looking, isn’t it? The original photographer, the subject, us looking at them now... It becomes a conversation, albeit a complex one. You wonder, did the subject understand the future implications of being rendered this way? Curator: Those ethical questions around consent and representation become even louder with time. What does it mean to preserve and display an image with such a loaded history? The photo prompts crucial discussions that require a sensitive, ethical lens. Editor: It’s haunting, I think. Sad. But maybe that's part of why we *need* to look at it, not turn away. To understand our history of objectification. It gives pause. I wonder how we might begin to deconstruct that… Curator: It all starts with critical engagement—by bringing intersectional theory to bear upon these historical works, and continuing that conversation as we work to promote representation that challenges social constructs. Editor: Okay, good place to start.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.