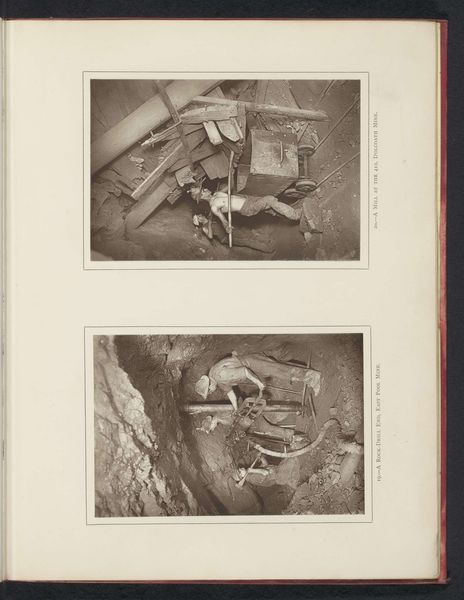

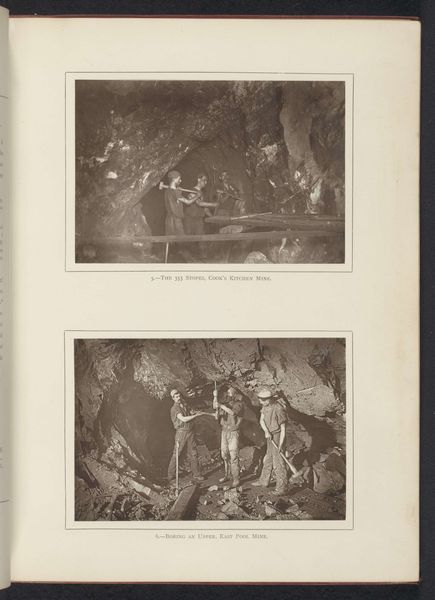

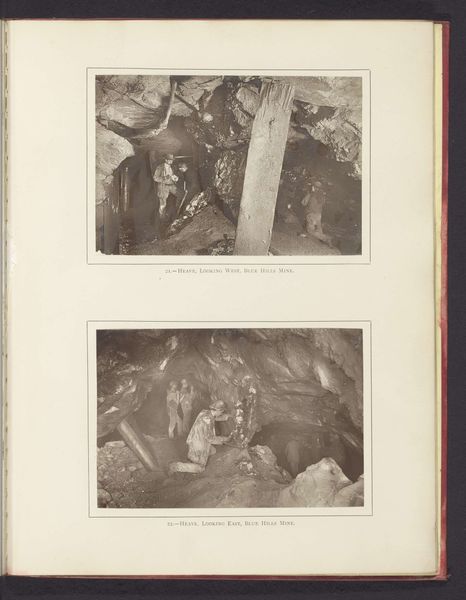

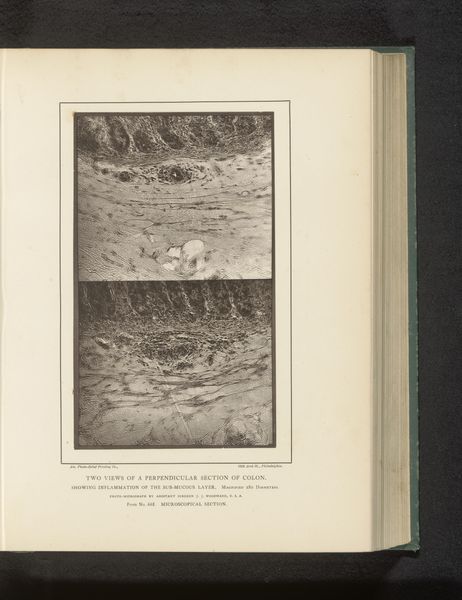

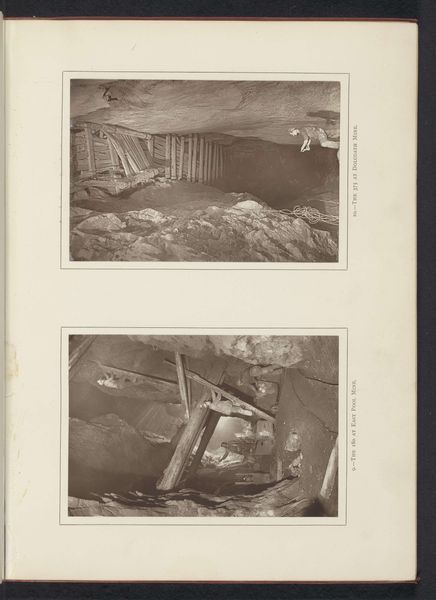

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

landscape

#

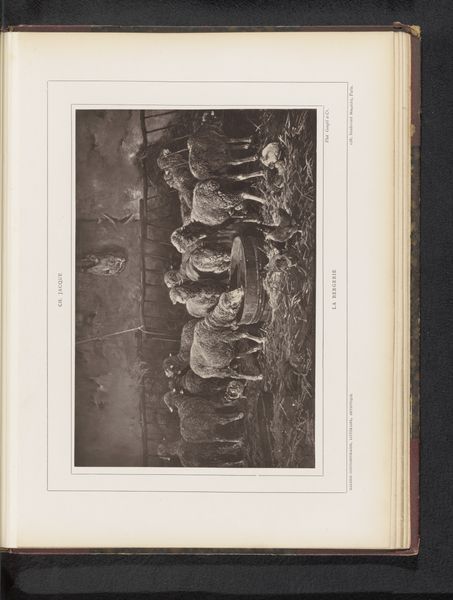

social-realism

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: height 243 mm, width 304 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

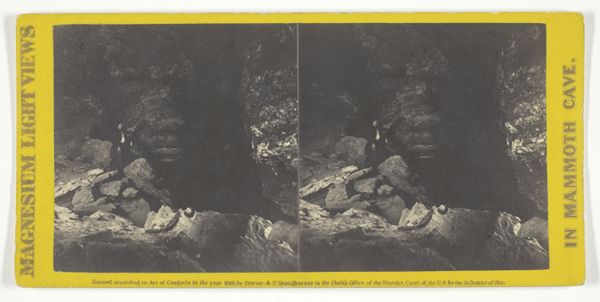

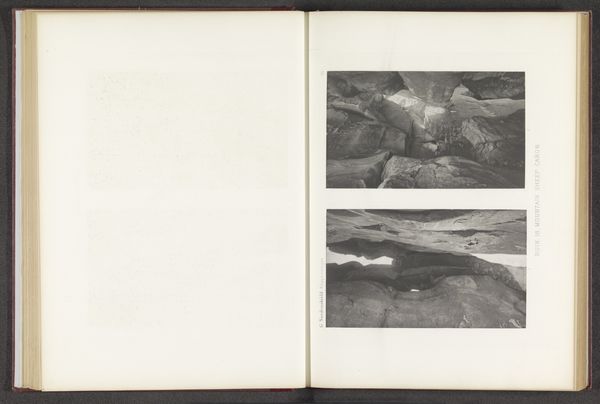

Curator: These images pulse with such palpable tension and darkness. The visual vocabulary—confined spaces, harsh light, the figures bent to their work— speaks of profound physical and psychological weight. Editor: Indeed. What we have here are gelatin silver prints by John Charles Burrow, dating back to around 1893. Titled "Delvende mijnwerkers in een mijn te Cornwall"— Cornish tin miners in a mine—they provide a rare glimpse into the dangerous world of industrial labor in the late 19th century. Curator: It’s a world defined by descent, isn’t it? Not just physically into the earth, but a symbolic descent. The ladder itself— such a primal symbol for ascension— becomes almost ironic here, offering only a temporary reprieve from the depths. The lack of distinct individual features also enhances the overall symbolism. Editor: Absolutely. Burrow’s work reflects a broader movement of social realism that sought to depict the realities of working-class life, especially its hardships. The advent of photography democratized this form of representation; It gave people like Burrow a tool with which to shine a light on unseen corners of society, influencing public perceptions about labour practices and prompting institutional reform. Curator: Looking closely, notice how the limited light doesn’t simply illuminate, it judges. Faces are obscured or cast in shadow, enhancing a sense of anonymity and emphasizing the repetitive, almost ritualistic nature of their work. We're not invited to witness their humanity so much as their subjugation. It’s deeply unsettling. Editor: Yes, and think about what Burrow, as a photographer, chose to reveal. Photography always involves choices about what to frame, what to leave out, and how to depict it. By presenting these images in a stark, unvarnished way, he’s taking a stand and prompting the viewer to grapple with ethical questions about industrial progress and its human cost. Curator: The fact that the photograph remains so visually arresting—and so uncomfortable—even now speaks to the enduring power of visual symbols to evoke powerful collective emotions. Editor: It reminds us that art plays a critical public role, both as a record and as a catalyst for social change. Curator: A potent reminder indeed of art's vital connection to life beyond gallery walls. Editor: A necessary lens, showing us both where we've been and inviting questions about where we're headed.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.