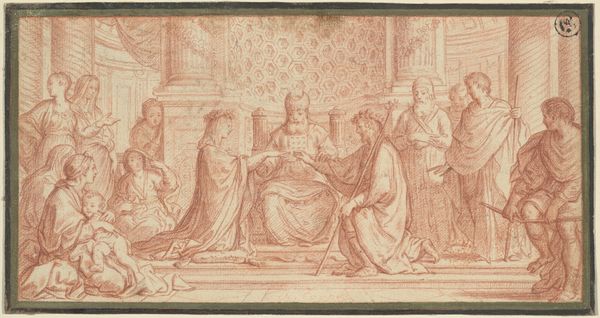

Madonna and Child with Saints Martin and Maurice (?) 1527 - 1533

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper, ink

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

ink painting

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

Dimensions: 12 1/4 x 9 3/4 in. (31.1 x 24.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This striking drawing, "Madonna and Child with Saints Martin and Maurice(?)," comes to us from Gaudenzio Ferrari, dating approximately from 1527 to 1533, part of the Italian Renaissance. It’s ink on paper, a medium that allows us to truly see the hand of the artist at work. Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by the stillness, almost a muted quality, despite the traditional religious subject matter. It’s very subtle. The lines seem delicate, vulnerable. Curator: It's interesting that you perceive vulnerability. From an art historical perspective, these Madonna and Child compositions served many purposes. On one level they certainly emphasize familial care and the divine. But further context tells us they also played a role as political imagery – signifiers of power for patrons. Editor: Absolutely. Thinking intersectionally, we can view the virgin figure not just as holy mother but as representative of idealized womanhood and associated societal constraints. Where does power lie, when this idealized figure is simultaneously venerated and confined? The presence of those masculine figures on either side really anchors that feeling for me. Curator: Yes, St. Martin and St. Maurice--or the presumed identities of these figures – also carries sociopolitical significance. We need to understand the role of these figures within religious institutions and how such organizations were perceived by a 16th century audience. Editor: The figures definitely represent power, perhaps a protective force around this mother and child. However, their gazes, or the overall flatness of the artwork seems to keep any strong emotional response in check. It is really, quite different, when one is accustomed to viewing similarly themed Renaissance works as large colorful canvases, and not on paper like this. Curator: The deliberate lines capture the essence, highlighting form and structure, don’t you agree? While maybe a work with colour or on canvas gives us a polished final image, these strokes make the thought process so readily evident to the viewer. Editor: And perhaps that access makes this drawing more interesting, in a way? Stripped down in medium, yet densely filled with sociohistorical resonance. This drawing gives us more to unpack. Curator: Absolutely. Its place in the Italian Renaissance, plus our awareness of religious and secular power structures in early modern Europe helps decode those lines of inquiry, right here, with a few lines of ink. Editor: Precisely. What appears straightforward opens into broader considerations about identity, history, faith and visibility when the viewer chooses to look beneath the surface of lines drawn in ink.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.