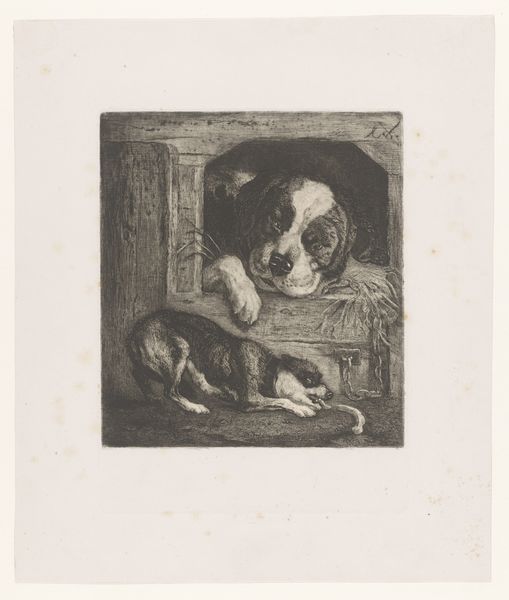

drawing, graphite, charcoal

#

drawing

#

impressionism

#

landscape

#

charcoal drawing

#

graphite

#

charcoal

#

charcoal

#

graphite

#

realism

Dimensions: height 191 mm, width 301 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What a striking piece! Auguste Danse created this drawing, "Dog in a Washtub at the Water's Edge," around 1889. It's currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It certainly evokes a mood. Somber, perhaps a touch melancholic. The monochromatic tones really amplify that feeling. Is it graphite and charcoal? Curator: Indeed. Danse employs both charcoal and graphite, mediums lending themselves beautifully to subtle tonal gradations. This work falls roughly within the Impressionist movement, yet one could argue there's a strong realism at play, especially in rendering the dog. It makes one wonder what the societal function of this drawing would have been. Did it have political intent? Editor: The image of the dog immediately grabs attention. Note how its head is hung low into what seems to be a washtub. It almost conveys a sense of weariness, perhaps symbolic of the working class, or a loyal animal reflecting the hardship of its owner's life. It's like a modern Pieta with a dog. Curator: That's a fascinating interpretation, framing it within the narrative of labor. Thinking about the history of animals in art, and indeed in society at the time, we might be seeing a symbolic representation of servitude, especially rendered in such humble, almost bleak surroundings. Dogs often stood for loyalty and servitude, right? Editor: Absolutely! The visual language suggests that, while dogs can represent positive qualities, this particular depiction subverts expectations, highlighting their dependence. And there’s a potent association between the washbasin and purity or cleansing – is Danse using it ironically, suggesting the dog or even the social order is beyond redemption? It resonates with a wider visual culture in European art that wrestles with symbolism to reflect reality. Curator: The placement on the edge of water certainly brings to mind themes of liminality, of boundaries between different worlds. We often find bodies of water acting as thresholds to symbolic meaning. And thinking about its later placement and reception, the work now resides in a national collection – what does its institutional display do to these inherent visual meanings? Editor: Precisely, does displaying such a melancholy image offer a commentary on the role and place of national heritage? This sombre representation asks profound questions, perhaps deeper than its deceptively simple imagery might suggest. Curator: It's definitely given me a lot to consider about the power of visual art to pose tough social questions, even over a century later! Editor: And for me, to keep searching beneath the surfaces, and see what we think we know from what we have been given as insight through enduring symbols.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.