Dimensions: height 103 mm, width 155 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

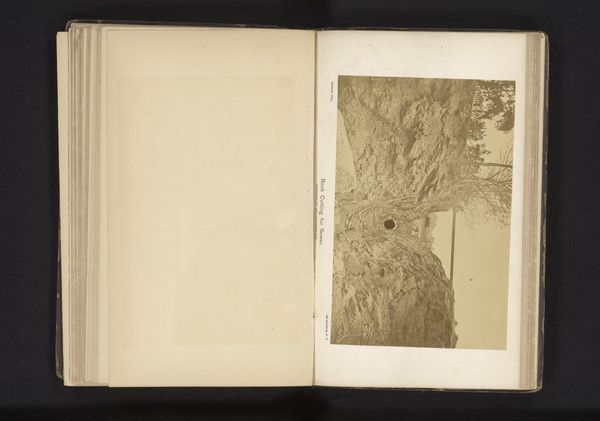

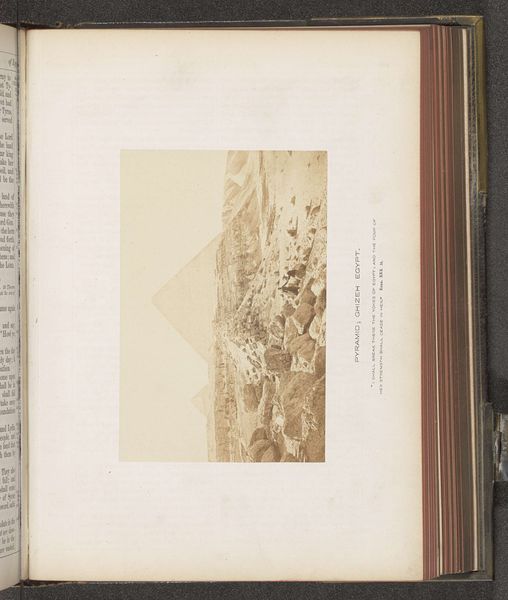

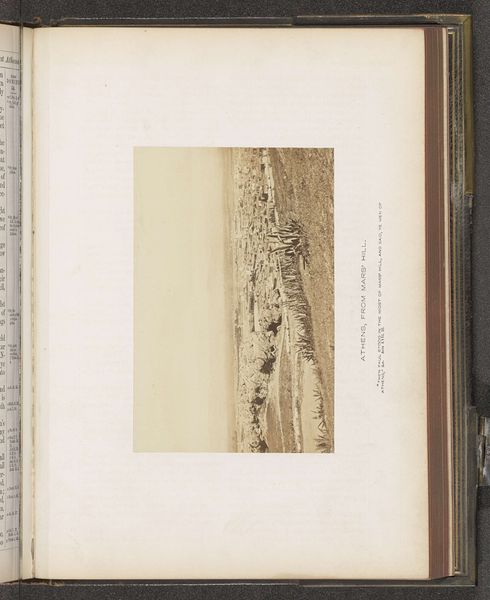

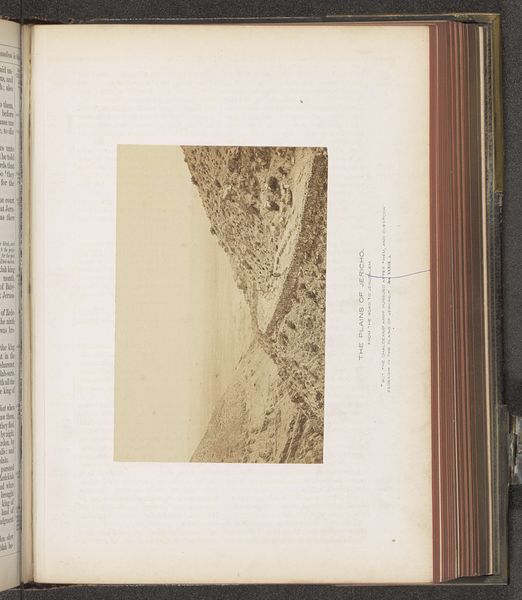

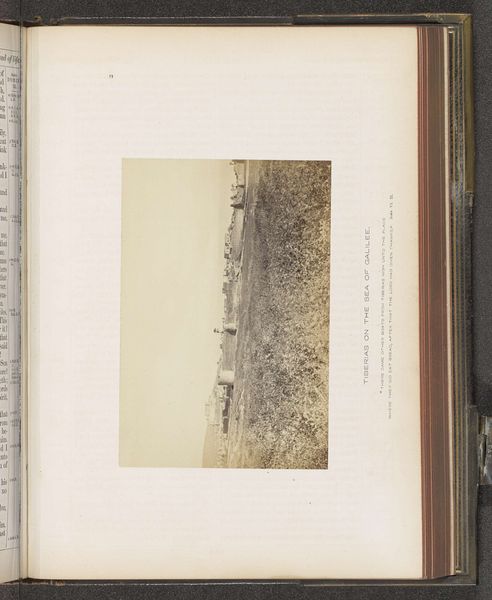

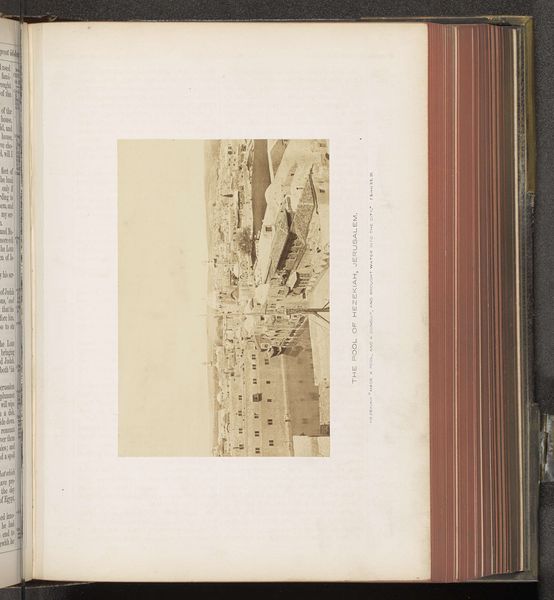

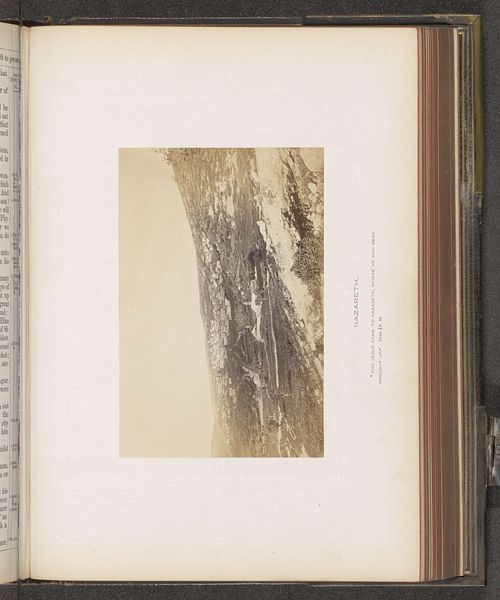

Editor: Here we have Francis Frith's photograph, "Gezicht op een berg, aangeduid met Hor," or "View of a mountain, designated with Hor," created sometime between 1850 and 1865. It's a gelatin-silver print. There’s a captivating stillness to it; almost meditative. The way the mountain face fills the frame is incredibly powerful. What do you see in this piece? Curator: Oh, Frith. He could find poetry in the dust of forgotten places, couldn't he? It's more than just a mountain, this. It's a monument to time itself, etched in stone. Do you see how the light catches those rugged edges, almost whispering stories of windswept plateaus and sun-baked earth? He's playing with orientalist themes, capturing a kind of biblical grandeur, but there's also this very modern quest for… accuracy, shall we say, that clashes with those romantic aspirations. What kind of emotional chords does it strike for you? Editor: Definitely a sense of permanence. A timeless, almost spiritual quality, yet I also detect that tension you mention—the weight of history versus the objective record. But what did viewers think when photography like this first emerged? Curator: Astonishment, my dear! Imagine seeing places deemed 'holy' with your own eyes – rendered so faithfully. Photography gave tangible form to long-held religious imagination. It blurred boundaries, collapsing space and time. Suddenly, the Levant wasn't some distant land in biblical tales, but a very real place... even if tinged with European sensibilities. Editor: That makes perfect sense. It’s really eye-opening to consider the impact of photography in that historical moment and context. Curator: Precisely. Each little sun-baked shadow, each rocky projection becomes part of something far bigger: a shift in how the world saw itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.