Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae: St. Peter's 1530 - 1580

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching, intaglio, engraving, architecture

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

intaglio

#

perspective

#

11_renaissance

#

geometric

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: sheet: 12 15/16 x 17 11/16 in. (32.8 x 45 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

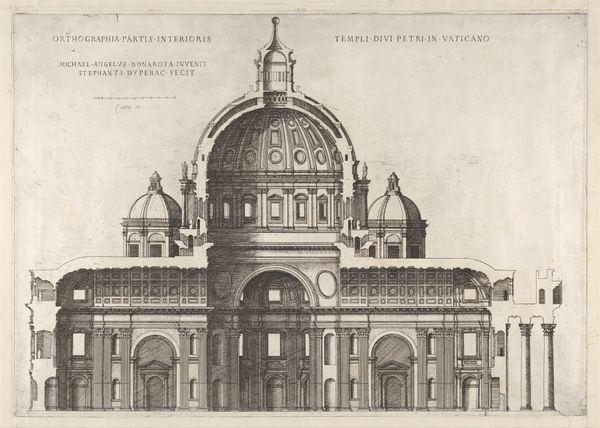

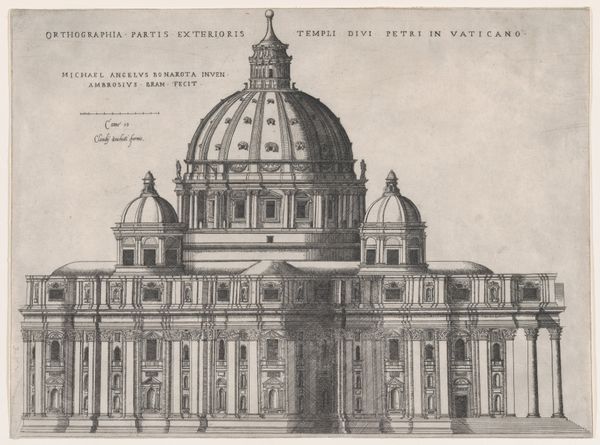

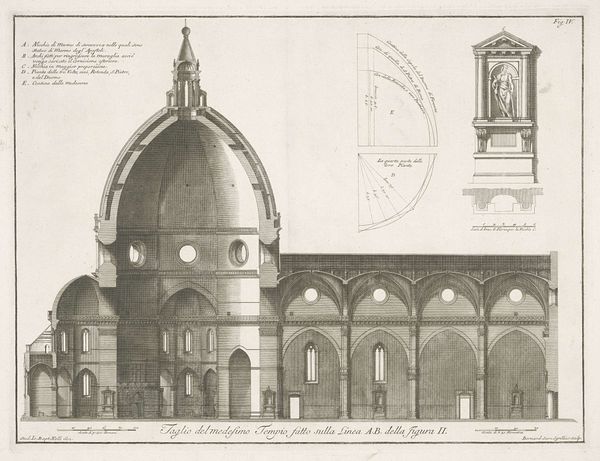

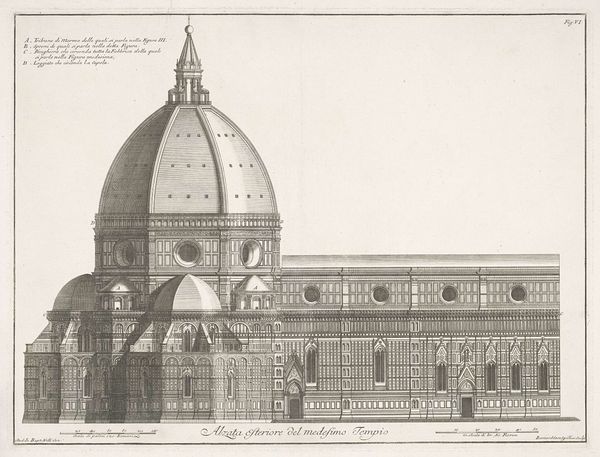

Curator: Here we have Étienne Dupérac’s engraving, "Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae: St. Peter's," likely created between 1530 and 1580. It's currently held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: It feels almost… surgical. Like a dissection. Cold, stark. There's something about the level of detail rendered in stark lines, cutting into the page with these fine etching and engraving marks that is striking, even a little unsettling. Curator: Precisely. Dupérac gives us a meticulous cross-section. The title itself, translating roughly to “Mirror of Roman Magnificence,” suggests it’s more than a mere architectural document. The “magnificence” speaks to the social and political power projected through this construction. Consider the sheer audacity of displaying interior secrets this way. Editor: Absolutely. Symbolically, the dome, so painstakingly rendered here, represents heaven's vault. Think of the emotional impact such a structure had on worshippers. This engraving isn't just about the building, it's about conveying an idea. The visual language elevates Rome, tying it to religious aspiration. Curator: And we can’t ignore that Michelangelo “invented” it as noted in the print's text – "Michael Angelvs Bonarota Invenit" and then it was realized and reproduced by Stephanvs Dv Perac as he "fecit", made it . It's a testament to the intellectual capital concentrated in the church, effectively merging artistry and spiritual authority to communicate its message and entrench a hegemonic position. Editor: Seeing the building laid bare like this—as lines and forms, but devoid of bustling figures—amplifies the underlying geometry, the faith placed in rational thought. How it conveys human capacity and capability in the face of something seemingly unknowable like faith and religion, a kind of propaganda I'd suggest. Curator: That's such an astute observation. We have to ask how it was seen by various people living during that historical period. Was the effect of it ultimately democratizing in the long-term or used as a tool of cultural expression? Editor: It's these kinds of images which enable us to interrogate how the world thought of itself then—how symbols function, still, shaping us even now. Curator: Precisely, this artwork encourages us to unpack history, dissecting how images functioned as instruments of power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.