Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

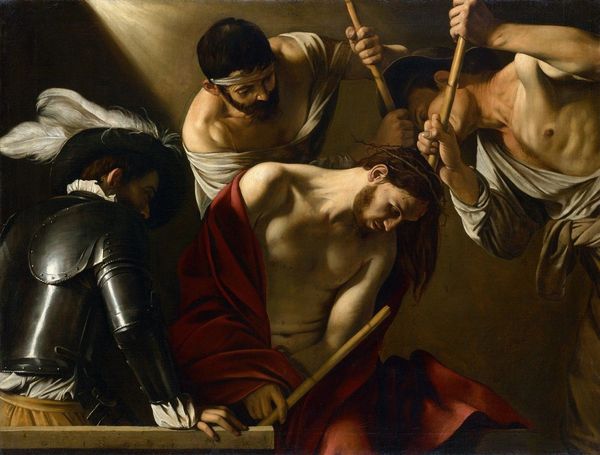

Curator: Well, let's turn our attention to this canvas created around 1600: Caravaggio’s "The Conversion of Saint Paul," a remarkable piece rendered in oil paint. What's your immediate take? Editor: Chaos, illuminated! There’s such dynamism, but it feels staged somehow. The horse's flank dominates the scene and that fallen figure... overwhelmed by divine intervention, perhaps? The lighting is dramatic, highlighting the raw physicality of it all. Curator: Indeed. It's a signature Baroque trait; the theatrical, emotional charge. But let's delve a little deeper into this pivotal moment in religious history, through a modern lens. We are faced with Paul, then Saul, a zealous persecutor of early Christians. He experiences a blinding vision en route to Damascus. How might Caravaggio be subverting or perhaps upholding prevailing power structures within the church? Editor: Interesting. For me, the symbolism hits harder initially. The horse, a recurring motif representing worldly power and strength, looms large over Saul, but he is rendered powerless. Blinded, humbled. And what about that light? A direct visual representation of divine illumination, but also a stark contrast, literally casting shadows of doubt and questioning on the figures surrounding him. I read it as humanity humbled by something greater than themselves. Curator: Absolutely, but let's also acknowledge the societal context in 17th Century Italy. Caravaggio wasn't simply illustrating scripture. How does his portrayal—a moment of absolute surrender and vulnerability—relate to ongoing religious and political upheavals? There is the obvious element of control by a "higher" power, a power that at the time was being violently fought against across social, political, and gender spectrums. This canvas feels as radical in 1600 as the man's lifestyle who created it. Editor: That’s a provocative reading! So the raw emotionality in this image carries both spiritual and sociopolitical weight, made even more fascinating when read through the iconographic implications of blindness. To be stripped bare like this implies both power and vulnerability. The figures surrounding him do look like they are protecting him from his vulnerability. They could very easily turn him on his side, but instead assist. A complicated representation of conversion on every level, personal and social. Curator: Precisely. A singular moment that reverberates far beyond its scriptural origin. It is as charged today as it was four centuries ago, and for me, in our current state of polarization, as politically potent. Editor: Indeed. It invites constant re-evaluation, both for the artist and ourselves.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.