#

pencil drawn

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

old-timey

#

19th century

#

pencil work

#

watercolour illustration

#

watercolor

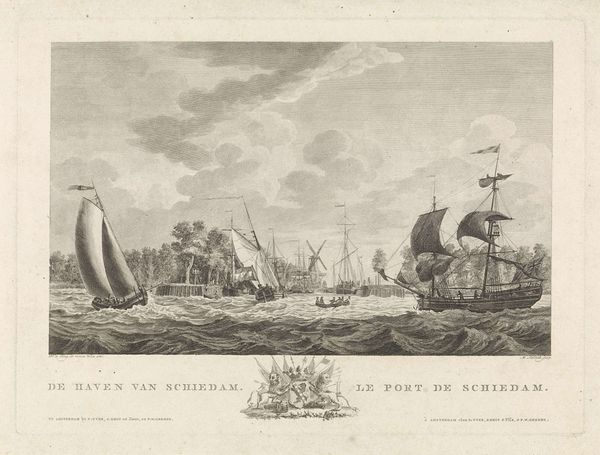

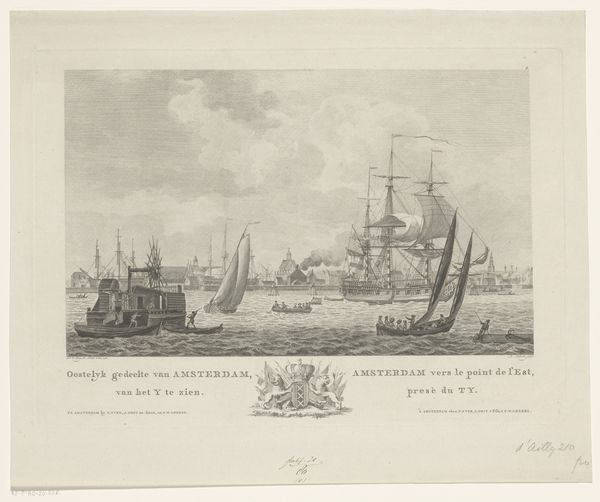

Dimensions: height 454 mm, width 588 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this print, “Gezicht op de haven van Brugge,” or “View of the Port of Bruges,” dating from 1759 and created by Noël Le Mire, I'm immediately struck by the detailed rendering of the ships. It feels incredibly busy but controlled. Editor: Absolutely! I’m immediately drawn to the interplay between the bustling harbor activity and the relatively subdued tonality of the pencil work. What paper was used, do we know? The toned surface seems integral to the overall effect, doesn't it? Curator: It does appear to be toned paper, which would have given the artist a mid-tone to work from, allowing him to create highlights and shadows with a greater range. Consider, too, that printmaking like this was not just about aesthetics. These prints served as a form of visual record, spreading ideas about architecture and engineering during a time when travel was less accessible. It becomes a vital visual document of maritime commerce. Editor: A record, yes, but also a form of propaganda. Note how the grandeur of the ships, the scale of the harbor – all of it promotes Bruges as a powerful trading hub. It’s a marketing tool crafted within a very specific economic context, showcasing Dutch maritime prowess in 1759. Also, did you notice the small human figures that adds perspective and an old-timey touch? Curator: A shrewd observation. Those figures provide scale, but also reinforce a social hierarchy. The figures on the shore seem engaged in labour, dwarfed by the vessels which facilitated their roles, reinforcing who benefits the most. Let’s also talk about the laborious engraving process and its cost, pointing towards wealth and power. Editor: Precisely. Even the aesthetic choices, like the light pencil work, speak to the cultural tastes of the period, the demand for detailed, yet refined, depictions of status. We see labor reflected in every aspect, from production of the print, to the activity represented within it. Curator: Exactly. And when we analyze its presence within the Rijksmuseum collection, it is important to see it as both a depiction of an important geographical landmark, but as a political device. A visual representation which promoted socio-political agenda. Editor: I find myself thinking differently about it now, appreciating it not just for its aesthetic value, but for what it says about the complex forces at play in 18th-century Dutch society. Curator: Indeed. A perfect illustration of how materiality and history intertwine!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.