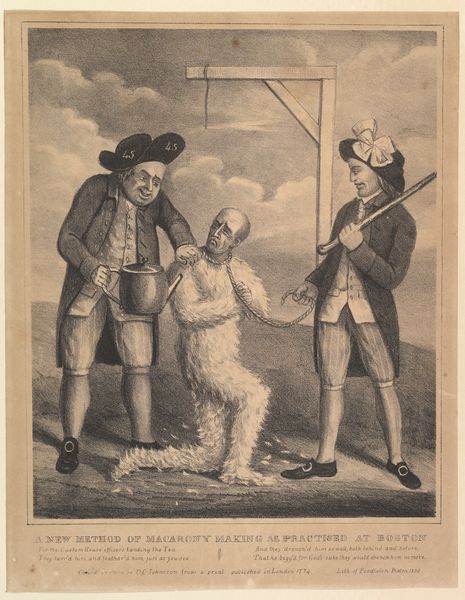

A New Method of Maracrony Making as Practised at Boston in North America 1769 - 1779

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

caricature

#

men

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: plate: 6 x 4 1/2 in. (15.2 x 11.4 cm) sheet: 9 3/16 x 5 7/8 in. (23.4 x 15 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

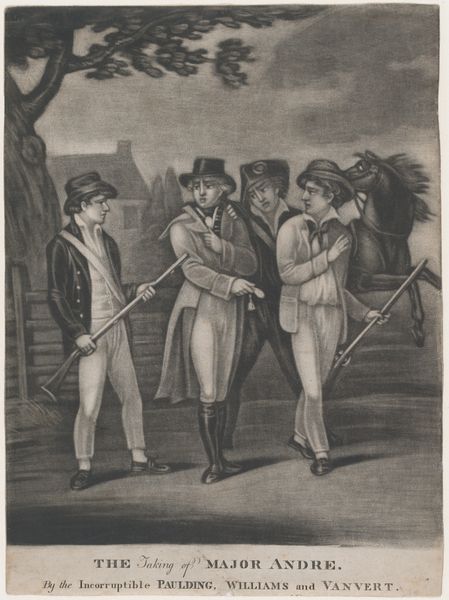

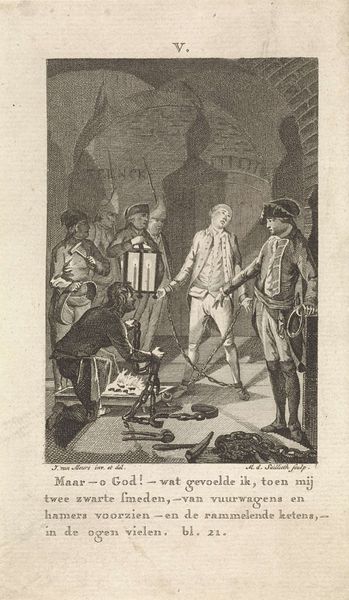

Editor: This print, titled "A New Method of Macarony Making, as Practiced at Boston in North America," dates to around the 1770s and is by Carington Bowles I. It's… unsettling. The scene depicts men seemingly torturing someone covered in feathers under a makeshift gallows. What do you see in this piece? Curator: It’s powerful, isn’t it? Immediately, I'm drawn to how the print utilizes satire to comment on power dynamics between Britain and America during the lead-up to the Revolution. Note the number '45' on one of the men’s hats; this is a reference to John Wilkes, a British politician who supported American colonists. Wilkes became a symbol of resistance against perceived tyranny. Do you see how that rebellious number connects with the scene of punishment depicted here? Editor: So, the "macarony" in the title—that's not pasta, right? I thought "macaronis" were a term for foppish men? How does that tie into Boston? Curator: Exactly. "Macaroni" was a derogatory term for British men perceived as overly concerned with fashion and continental European trends, often associated with effeminacy and perceived moral corruption. Consider how the print conflates this decadent British identity with violence being inflicted on what seems to be a colonial figure, the individual being “tarred and feathered” and in distress beneath a symbolic gallows. We need to ask, what is the artist saying about the supposed refinement and authority of the British Empire? Is it civilized or barbaric? Editor: Wow, I didn’t pick up on that at all. It makes me wonder how the print was received then. Was it simply anti-British propaganda? Curator: Perhaps. But good propaganda usually resonates with existing social anxieties. Consider also the potential xenophobia embedded in caricaturing difference. It speaks volumes about the anxieties and justifications fueling a revolutionary climate. What did *you* take away from considering these historical layers? Editor: I initially just saw violence, but now I recognize this print is filled with complex socio-political commentary. It really makes me think about how we interpret satire today! Curator: Absolutely. And understanding its historical context adds a crucial layer of depth.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.