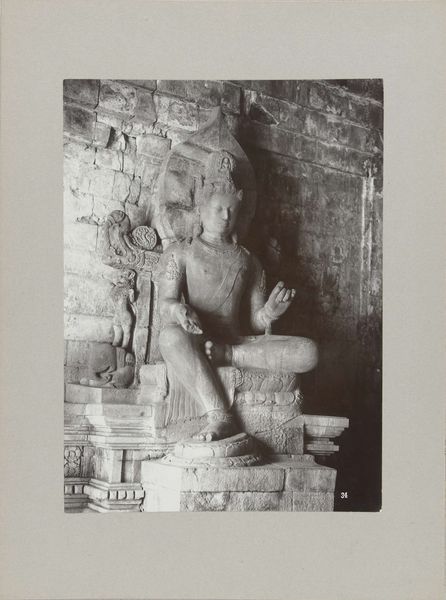

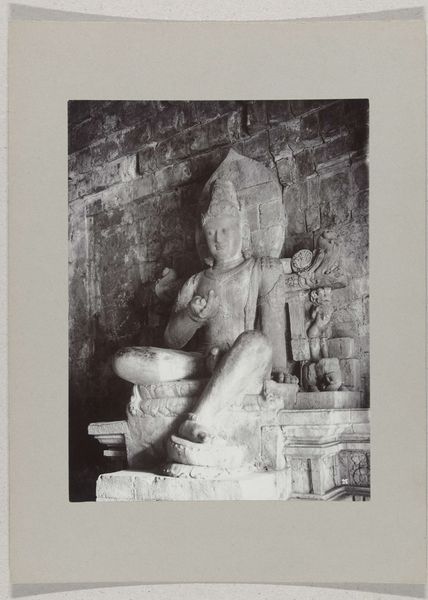

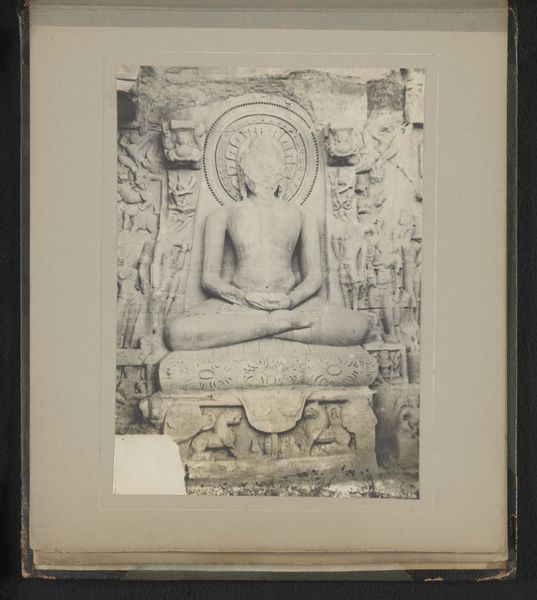

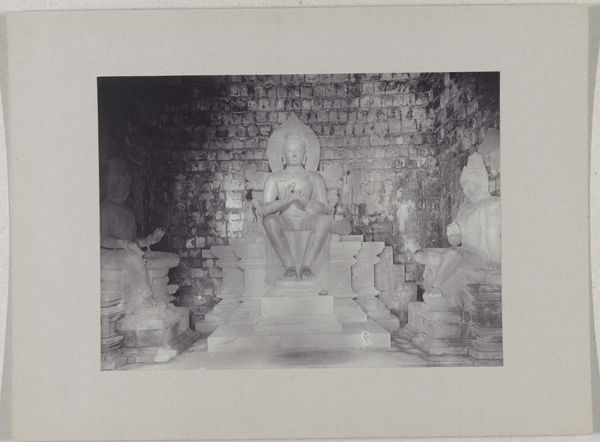

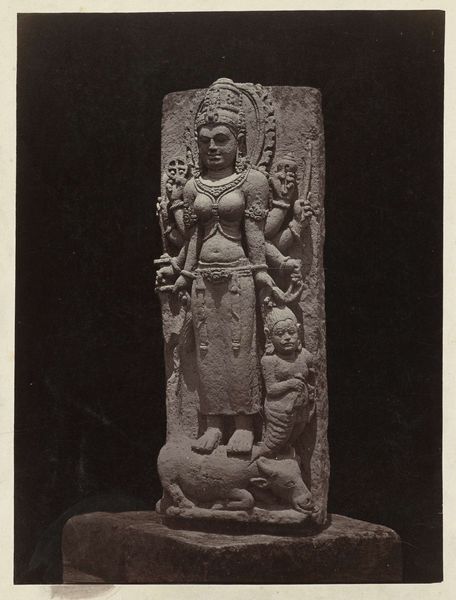

Beeld van een van de twee koningszonen in de Tempel Mendoet ten zuiden van Magelang, Nederlands-Indië. c. 1895 - 1915

0:00

0:00

photography, sculpture, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

sculpture

#

asian-art

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

sculpture

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 241 mm, width 174 mm, height 243 mm, width 329 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

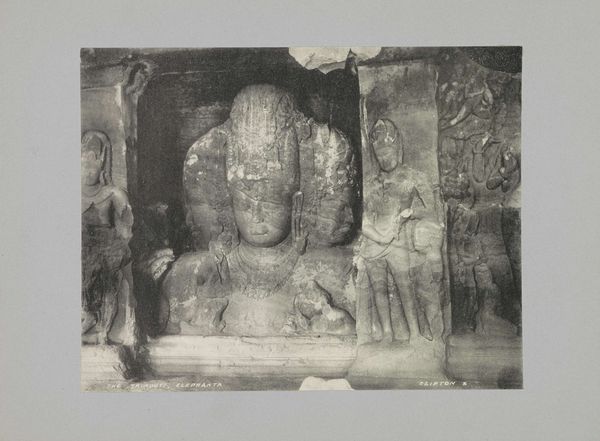

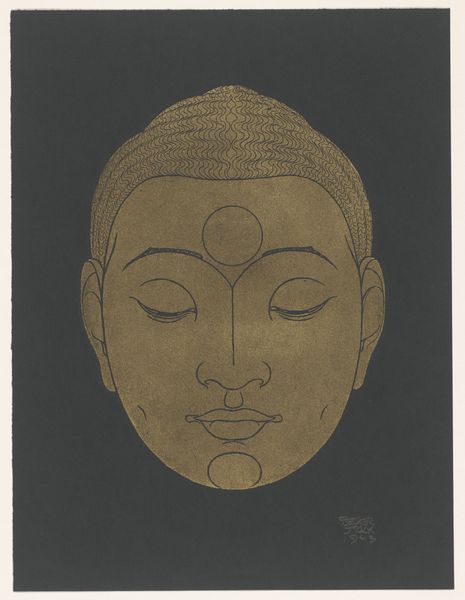

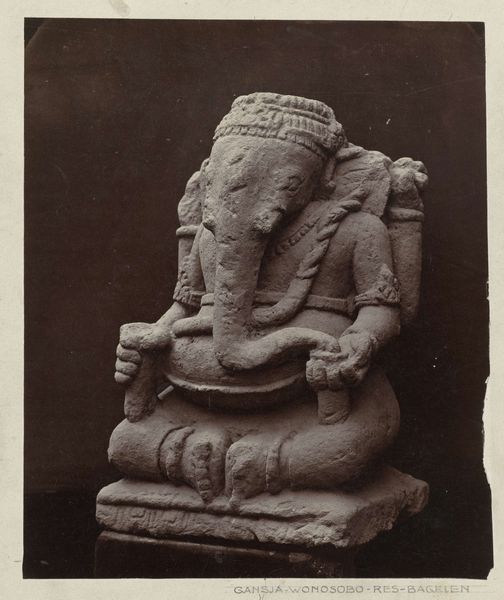

Curator: Here we have a gelatin-silver print taken sometime between 1895 and 1915, attributed to Onnes Kurkdjian. The piece, titled "Beeld van een van de twee koningszonen in de Tempel Mendoet ten zuiden van Magelang, Nederlands-Indië," depicts a sculpture in, as the title suggests, the Mendut Temple. Editor: Whoa, talk about a mood piece. It's got this eerie, almost ghostly vibe, doesn't it? The sculpture looks solid, eternal, but the faded black and white and the rough edges of the photo make it feel like it’s a forgotten dream. Curator: The photo itself serves as a cultural artifact, a kind of document that also reveals much about Dutch colonial interest in the region, immortalizing the temples in image. The artist plays with the contrast, focusing mainly on the serene face, and directing us away from the hands held in symbolic gesture. Editor: Absolutely. I am drawn to his pose. Sitting, so self-contained. And the wall behind him—those ancient bricks feel like they’re whispering stories, if that makes sense. Is this image really history, a relic of the past, or an invitation to look inwards at our own human foundations? Curator: Both, I think. Buddhist iconography in general—the lotus position, the mudras—always asks us to engage our own contemplative, historical, and psychic states, connecting this serene and unknowable king’s son to larger principles. This representation in stone certainly resonates on levels beyond historical documentation. The gesture alone invites one in. Editor: Right? I love the play of textures, too. The smoothness of the stone sculpture against the rough brick, then the way the photographic grain sort of unifies it all. You said "serene" earlier... to me the photo teases with both, that sense of calm, but also this gnawing feeling of something being lost to time. Curator: Perhaps that feeling of loss you mention is what gives the portrait of a sculpture its emotional resonance for a modern viewer. Editor: Exactly! Well, either way, this king’s son has got my imagination running wild. Curator: Indeed. It’s a powerful photograph, one that allows us to contemplate deep cultural and historical meanings within the delicate bounds of captured light and shadow.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.