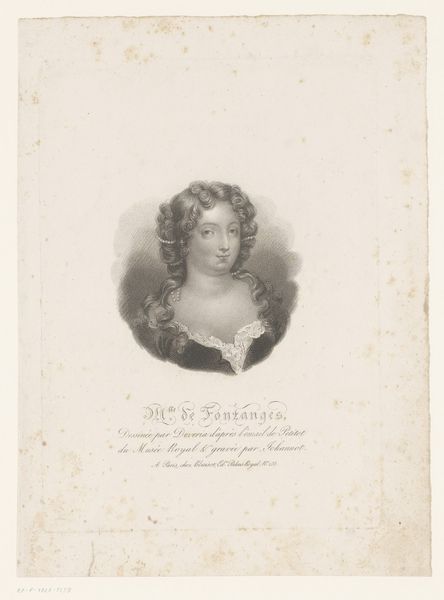

drawing, print, paper, pencil, chalk, graphite

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

paper

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

chalk

#

graphite

#

academic-art

#

realism

Dimensions: 196 × 130 mm

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Looking at this pencil and chalk drawing of Mlle de Fontanges by Eugène Devéria, created around 1832 and currently residing here at the Art Institute of Chicago, I'm struck by the direct gaze and the elaborate coiffure. It’s a fairly straightforward portrait, yet it suggests a powerful persona behind those eyes. Editor: Indeed. The image immediately evokes a sense of fleeting beauty and perhaps even impending tragedy, given what I know of Fontanges. There's a melancholic softness to the features, emphasized by the wispy rendering of her hair and the delicate lace. It feels almost ethereal. Curator: Devéria's decision to render the subject in pencil and chalk rather than paint lends it a sense of immediacy. It also hints at the role of the portrait within the court—often distributed and copied, this portrait plays on the economy of images which were tied to displays of wealth and class. Editor: I'm especially drawn to the choice of the medallion format itself. Medallions, historically, have conveyed power, remembrance, and often, the idea of enduring legacy. However, given Fontanges' relatively short and tumultuous life as a mistress of Louis XIV, the medallion feels ironic, doesn’t it? It’s as though Devéria is consciously playing with the viewer's awareness of history, contrasting the intended symbolic weight of the format with the subject’s actual fate. Curator: Perhaps. It’s worth noting the broader cultural fascination with figures like Fontanges in the 19th century. During the July Monarchy in France, there was a growing fascination with past eras as legitimizing precedent, including the figures who populated earlier courts. A portrait like this might then evoke nostalgic connections with powerful French monarchs, using their likenesses to convey legitimacy and power. Editor: I agree; it does echo earlier periods and styles, in spite of being made much later. Thinking about Fontanges, the extravagant hairstyle, typical of the Louis XIV period, acts as a symbol of both beauty and status. It represents the elaborate artificiality of courtly life, almost a fragile edifice built upon transient favors. It emphasizes both her perceived beauty and that superficial world. Curator: The context of 19th-century France is key here; this is more than a simple portrait of an alluring woman from a distant past. Rather, it's an engagement with a carefully curated narrative. This places this portrait in conversation with French debates about monarchy and national identity during a period of tremendous transformation. Editor: Absolutely. What initially struck me as a purely aesthetic depiction becomes a layered symbol of power, memory, and societal norms. The subtle tension Devéria creates makes us reconsider how we understand symbols over time. Curator: It certainly speaks volumes about the role of portraiture in shaping collective memory and projecting authority within specific political landscapes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.