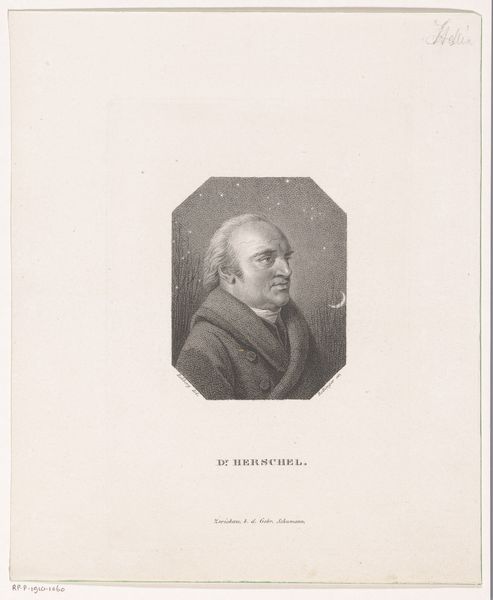

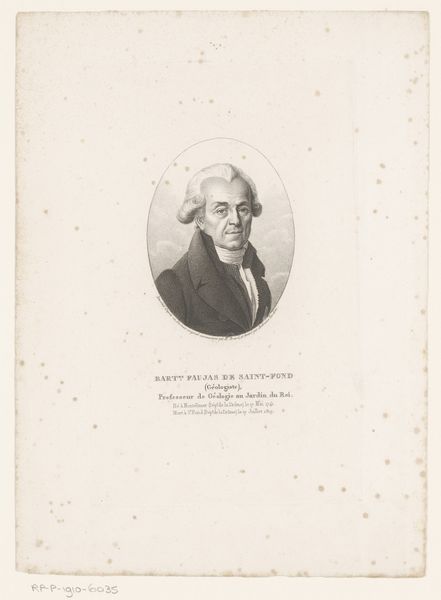

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

form

#

pencil drawing

#

line

#

pencil work

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 207 mm, width 119 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have "Portret van Pierre François Keraudren" made sometime between 1818 and 1832 by Charles Aimé Forestier. It's an engraving, so a print. The precision of the lines is quite striking. What's your perspective on how the medium influences the message here? Curator: Considering it's an engraving, we need to examine the labor involved. Think about the painstaking process of carving those lines into a metal plate. This isn't some quick sketch; it's a deliberate act of production. How might that affect our reading of Keraudren's status? Editor: Well, it certainly suggests he was someone important, deserving of that level of skilled labor and material investment. Was engraving a common medium for portraiture then? Curator: Yes, but think further. Who had access to engravings? This image, existing as a print, would have circulated, making Keraudren's image accessible to a wider, though still relatively elite, audience. This process of reproduction impacts his social visibility and perhaps even his perceived authority. Are we looking at a democratizing effect here or simply a broader distribution of power? Editor: That’s a great point. The act of reproduction changes the meaning itself. It's not just about Keraudren anymore, but about how his image is consumed and distributed. I hadn't considered that. Curator: Exactly. And considering Neoclassicism's emphasis on order and reason, how does the very *act* of engraving, a highly controlled and precise process, reinforce those values materially? Editor: So the material and the process aren’t just secondary to the image; they actively shape our understanding of the subject and the values of the time. Thanks, that makes me think about prints in a whole new way. Curator: Precisely. Analyzing the materiality encourages us to question what stories the artwork tells beyond its surface representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.