print, photography

#

black and white photography

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

black and white

#

orientalism

#

monochrome photography

#

cityscape

#

monochrome

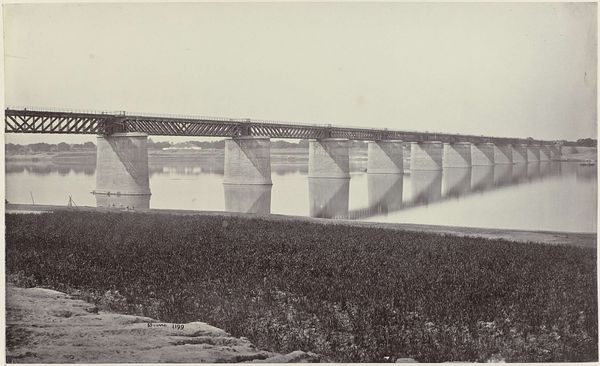

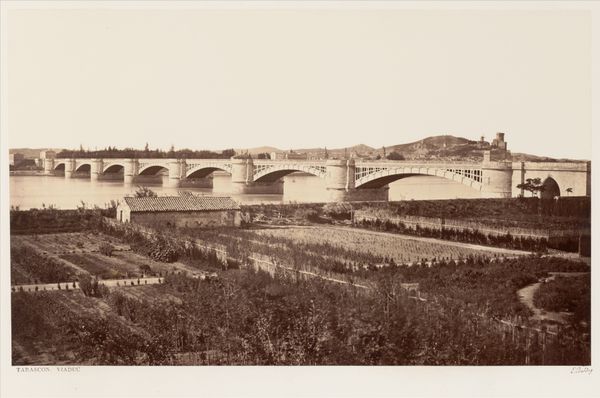

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 140 mm, height 124 mm, width 184 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have A.G.A. van Eelde's "Bridge over the River Zendeh Rud, Isfahan, Persia," a black and white photograph, likely from 1925. It's a striking cityscape, almost dreamlike in its simplicity. How do you interpret this work? Curator: I see this image through the lens of orientalism and colonial power dynamics. These photographic depictions of Persia, now Iran, were often framed by Western gazes. Consider how the photograph emphasizes the “exotic” architecture while potentially eliding the complexities of local life. To what extent do you think it reinforces or challenges stereotypes prevalent at the time about "the East"? Editor: I hadn't really considered that aspect. The photo itself seems quite objective, simply documenting the bridge and the landscape. Curator: But even that so-called objectivity is constructed. Think about the photographer’s choices: the angle, the framing, the decision to present it in monochrome. These decisions contribute to a particular narrative. Also, notice the figures atop the bridge—are they depicted as individuals with agency, or as anonymous components of a distant scene? Editor: They definitely seem more like anonymous components. Does the photograph's composition have an impact, besides reinforcing distance? Curator: Absolutely. The long horizontal span of the bridge might symbolize the vastness and perceived emptiness of the land. Also, we might wonder who had access to photography at this time and how their perspective shaped the representation of Isfahan. Can we analyze this image alongside, for instance, written colonial accounts of Persia to draw meaningful links between representation and power? Editor: So, beyond the immediate aesthetic, there's a deeper story about how the West saw, and perhaps, controlled, the narrative of the East. Curator: Precisely. By acknowledging the historical and political context, we can engage with this photograph in a far more critical and informed way. Editor: That really changes how I see this photograph now. It's not just a landscape; it’s a document embedded in a much larger discourse of power. Curator: Exactly. And hopefully it prompts us to question whose perspectives are privileged in historical representation and to seek more inclusive narratives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.