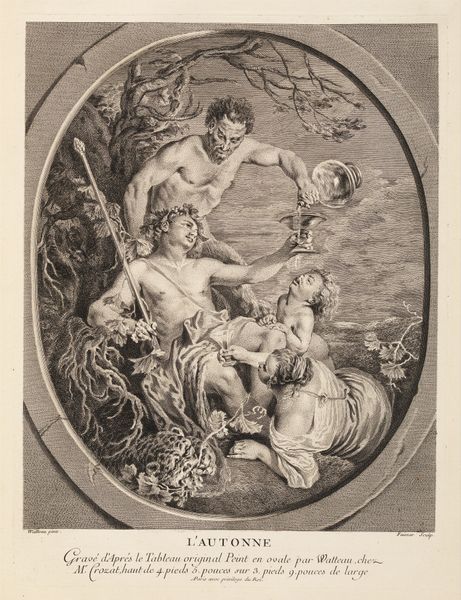

drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet (trimmed): 12 5/8 × 10 1/4 in. (32.1 × 26 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So, this print, called "Earth" by Jean Daullé, dates from around 1743 to 1753. It's an engraving, depicting these cherubic figures with grapes, almost like a Bacchic scene. There's an interesting mix of abundance and languidness... What strikes you when you look at this piece? Curator: Well, immediately I think about how allegory and prints like this functioned in the 18th century. Consider the dedication inscribed below – "Dedicated to His Excellency…" – art wasn't always 'art for art's sake.' There was a strong link between patronage, the ruling classes, and the creation and dissemination of images. Do you think this print served a purely decorative purpose? Editor: I suppose not. Given the aristocratic dedication, it must have been meant to communicate something about status or even political leanings. But what about the subject matter itself, the cherubs with grapes? Curator: Exactly! These weren’t random choices. The imagery of abundance and fertility directly relates to Earth as one of the classical elements. Consider, too, how the "Earth" theme might legitimize claims to land ownership, wealth and power within a specific social hierarchy. In essence, it transforms something physical, like the land itself, into an abstract visual symbol that reinforces existing social structures. Editor: So the print wasn’t just showing "Earth;" it was making an argument *about* earth, wealth and those in power. That’s a really different way of thinking about it. Curator: Precisely! Looking at the politics of imagery and who benefits from its circulation can offer deeper insights. The engraving technique, the scale of production – these elements facilitated wider distribution amongst a specific demographic. How do you think this availability shapes its significance? Editor: I hadn’t considered that mass production, in a way, created a more powerful endorsement and dissemination of these messages among privileged audiences, something that a unique painting wouldn't be able to achieve. Fascinating. Curator: Indeed. It's been illuminating for me too, to re-examine the mechanics of art, its public role, and imagery as power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.