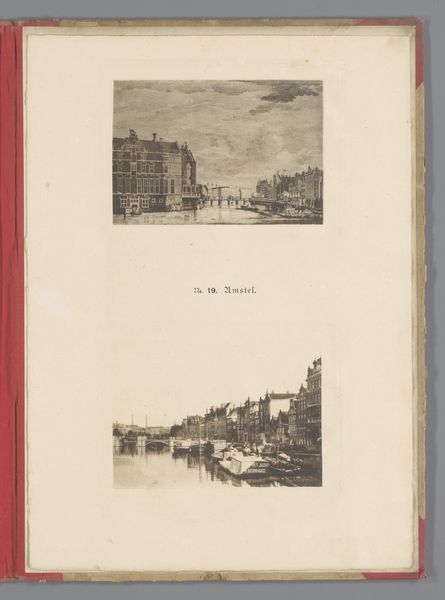

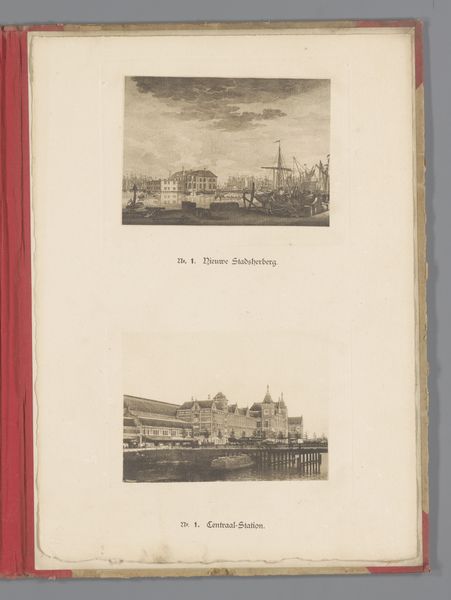

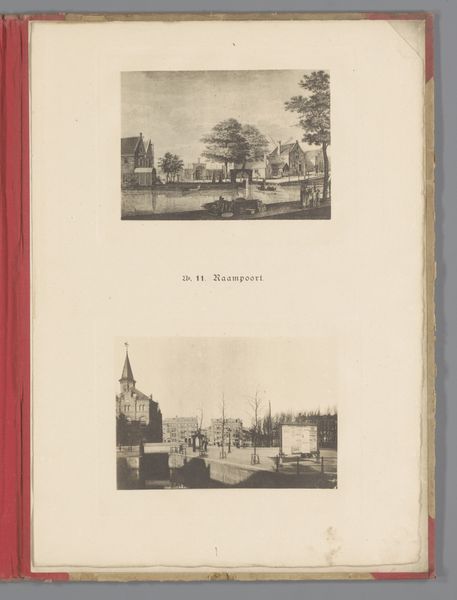

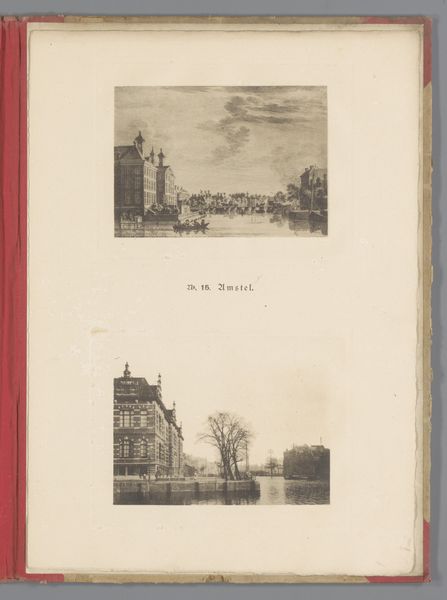

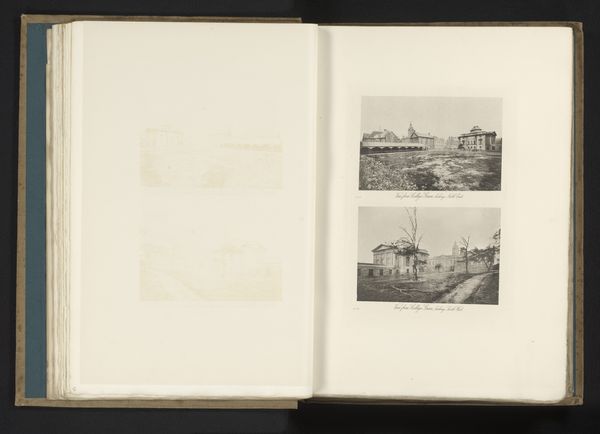

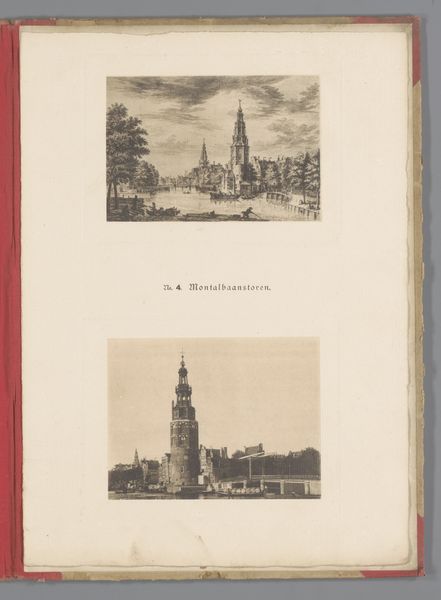

Twee gezichten op het Kattenburgerplein te Amsterdam, waarvan één reproductie van een prent met de watersnood in 1775 door Noach van der Meer II 1890 - 1900

0:00

0:00

anonymous

Rijksmuseum

lithograph, print, etching

#

dutch-golden-age

#

lithograph

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

cityscape

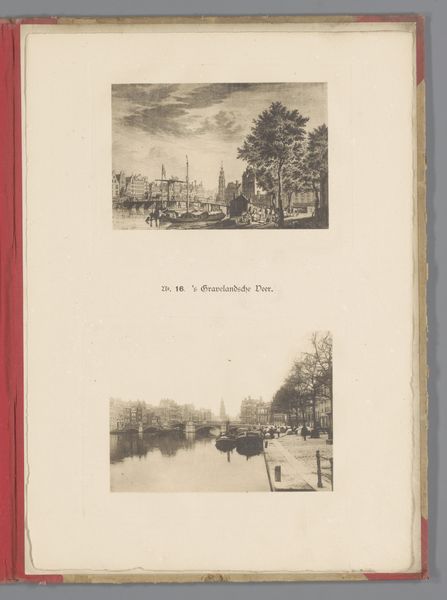

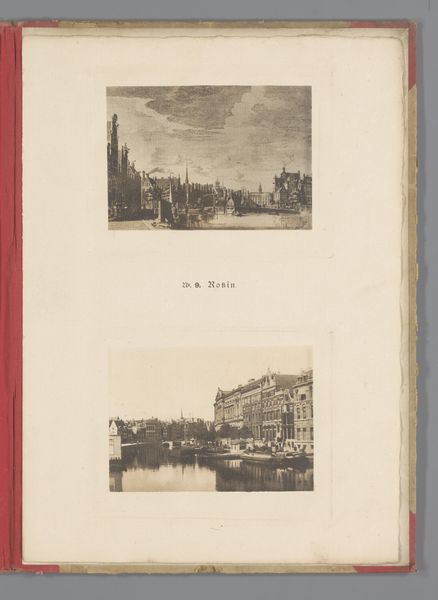

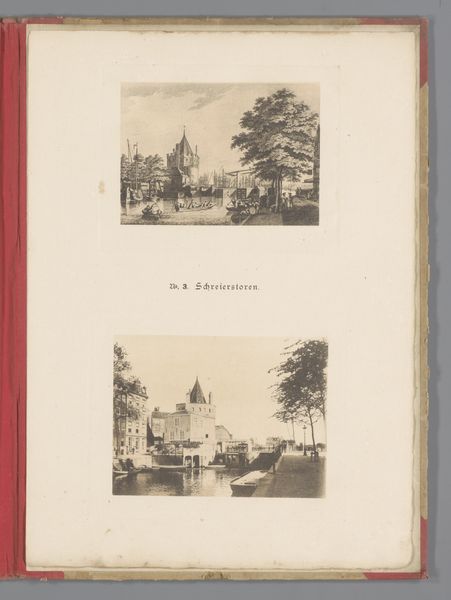

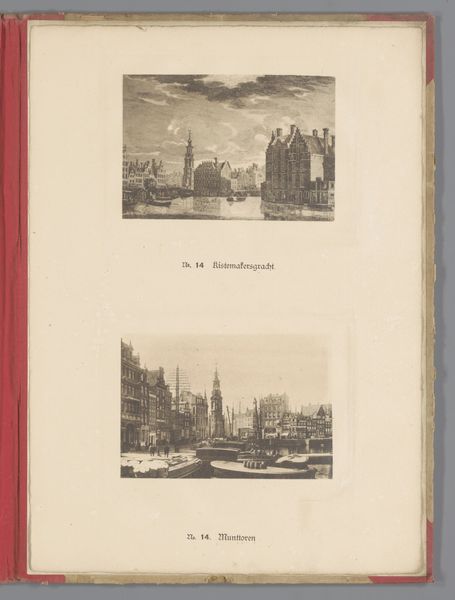

Dimensions: height 348 mm, width 250 mm, height 85 mm, width 138 mm, height 99 mm, width 147 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is an interesting composite print. It's titled "Twee gezichten op het Kattenburgerplein te Amsterdam," dating to between 1890 and 1900, and created by an anonymous artist. The print combines an etching and lithograph. The upper register contains a depiction, a reproduction of a print actually, of the flood of 1775. The second register shows the docks in a later moment in time. Editor: It strikes me as quite somber. The gray tones and the depiction of the flood create a sense of unease, which is only slightly relieved by the somewhat serene rendering of the industrial docks below. Curator: Considering the processes, using etching for the flood suggests the manual labor of recreating the historical image, highlighting printmaking's role in preserving narratives. Switching to lithography for the docks perhaps alludes to the mechanization of labor through advancements of production tied to port activity. It's interesting how combining them suggests that old technologies help document a newer landscape. Editor: That tension between historical record and industrial progress is central, isn’t it? Look at the visual weight: the scene of environmental devastation, with what appears to be displacement, sits above a scene dominated by trade and industry. You’re absolutely right that juxtaposing old with new hints at larger social, political, and economic transitions. The port represents the future, of course, while the flood embodies a moment of historical trauma. The arrangement underscores the tension between progress and memory, and it seems, vulnerability to ecological crises in general. Curator: And let's remember the circulation of these prints. These images probably went beyond the scale of "fine art" meant for wealthy patrons to be reproduced in books, newspapers, perhaps reaching a wider audience than paintings in the 17th century ever could. This is the democratization of the landscape through image production. Editor: Absolutely, placing this artwork in the context of print media underscores its accessibility, which expands its function beyond pure aesthetics. In effect, it’s a portable piece of shared cultural knowledge, reminding its audience of their history while also presenting them with a view of the rapidly evolving present, and its impact on the laboring class of people, who could also consume them. Curator: Understanding its material composition alongside the context reveals so much. Editor: Indeed. It encourages us to engage critically with questions of memory, labor, and environment and technological advancement in the city.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.